[**This article contains a spoiler of the movie Super Salaryman**]

A few days ago, while riding the bus, I tried to get rid of my boredom by re-watching Super Salaryman (in Thai: Yodmanud-Nguenduen), a Thai comedy-drama movie that was released in Thai cinemas in December 2012. Despite being a comedy, I felt that the film reflects certain issues and problem that can be found in the everyday life of office workers in Thailand. Central to the office in Bangkok, Super Salaryaman uncompromisingly, yet in a comical way, presents the intensive rhythm of the lives of Thai salary men and women as well as posing a question to problematise the idealised notion of the dream job imagined by many office workers in Thailand today. These critical messages are soundly delivered through the characterisation and the dialogue of the main characters, as I shall explain in detail in the following review of the film.

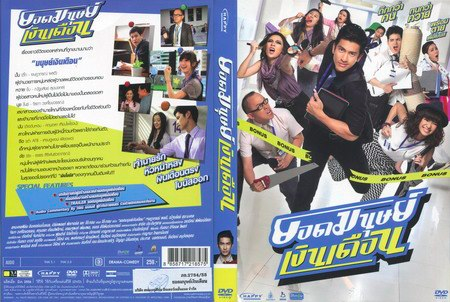

[The caption from the upper left to upper right reads “can’t get sick, can’t be late, if dead, inform in advance”]

Super Salaryman is about the lives of the employees of a fictional company named SK Company, who struggle in meeting the company’s deadline of a new product launch. The film is a production of Sahamongkol International, the rival studio of the famously known GTH. It was directed by a first-timer Wirat Konghengdee. Despite being his first film, Wirat manages to offer a genuine experience of Thai office life in a high-rise building in metropolitan Bangkok. Led by a highly motivated manager, Pun (played by the experienced and good-looking Jessadaporn Poldee), the SK Company’s employees are assigned by the company’s board, with only a little time left, to launch a new product by the end of the new year season. Feeling a bit uneasy about the tight deadline, the employees cannot reject or postpone the assignment as they are afraid of losing the end-of-year bonus. And as one could predict, their road to the bonus is not full of roses. Pun and his colleagues encounter bad fortune and accidents during their preparation for the presentation of the pilot product.

Apart from the struggle for the bonus, Super Salaryman also depicts the personal lives of each employee, together with issues which can commonly be found in many Thai offices. These issues include, for example, the seniority and hierarchical system of the workers. Jue, a young trainee, has to do almost everything his senior colleagues ask in order to prove himself and pass probation. He is also pressured by his family, which has prematurely seen him as a well-established businessman, despite the fact that he is still only a trainee. Another example can be seen with Nun, the finance manager who ironically always has financial problems. Nun desperately wants to find a new job in order to gain a higher salary. Yet, because she has established a close bond with her female colleagues, she finds it difficult to change job. In addition to the lives of these white collar workers, the film also portrays the lives of the working class. Aunty Ju, a company housemaid who receives lower pay, is often seen taking some advantages from the company’s facilities for her personal use. Although these issues may seem over dramatised, the director, Wirat, manages to present them in a comical and satirical way. This prevents Super Salaryman from falling into the pure drama genre that could hardly be sold in Thailand these days. The added humour still, however consists of elements which can ‘bite the heart’ of many Thai salary men and women in the audience.

The depiction of a dramatic yet hilarious story of white-collar workers, as done in Super Salaryman, is in fact not a new phenomenon in Thai film. Other films have taken on a similar subject. One that clearly visualises this theme is the highly popular 2009 comedy drama, Bangkok Traffic Love Story (Rod-Fai-Fah Maha Na-Ter, dir. Adidorn Teesirikasem), a film about two white-collar workers who have different working hours but meet and fall in love on the Bangkok Sky Train (BTS). In 2011, there was 30+ Single on Sale (30+ Sod-On-Sale, dir. Senapech Puttipong), a film about a 30-year-old single office lady who falls in love with a young owner of a pork BBQ stall. In 2012, there were ATM Eer-Rak Er-Ror (Error ATM Error Love, dir. May Tharatorn), a film about a dating couple who are both employed by a bank that has a strict no-dating policy for its employees; and ‘First Kiss’ (Rak Sudtai Ti Paina, dir. Keerati Nakintanon), a film about a 30-plus-year-old single office lady who falls in love with a high school student. These movies, despite taking on a similar subject as Super Salaryman, make use of the white-collar characters only to create a variation in the love and drama stories of the Thai young adult middle class. For example, in the successful Bangkok Traffic Love Story, the completely different working hours of the two main characters makes the audience wonder whether they would end up together. However, for Super Salaryman, the film not only takes on the lives of the office salary men and women in a Thai business district, but also exposes the issues and situations that can commonly be found in their office. More importantly, what seems to significantly set Super Salaryman apart from the rest is that it tackles the perception of ‘the dream job’ that is prevalent among Thai white-collar workers. These workers suffer from their job routine and believe that ‘being your own boss’ will give them a better life. The film conveys this issue through the story of Pun, the manager of SK Company and the main protagonist of the film.

Pun is characterised as a well-organised, determined, and dedicated employee. Pun’s goals are to climb up the ladder of the salary man’s life, to become financially successful, and to instil the sense of security to the future life with his fiancée, Joy. Wirat successfully portrays these characteristics through Pun’s own dialogue, which sounds direct, uncompromising, and professionally rational. This can be recognised, for example, when Pun assigns tasks to his colleagues in the situation of them facing a tight deadline. Even so, Pun’s professional attitude is made to face with an important conflict when he discovers that his fiancée wants to quit her office job and opens up a bakery shop. As a good partner, Pun at first tries to explain to her that she should not quit her job just yet, for the sake of their financial security. Things get convoluted later on when Pun is promoted by his company for a new position abroad, and he wants to take his fiancée with him. This puts pressure on his fiancée, as Pun’s accepting the new position would shatter her dream of running a bakery shop. At the end, this situation leads them to break up. Unable to understand their separation, Pun angrily bursts out a rhetorical question to Wai, his secretary. The question he asks, according to my understanding, crucially sums up the whole idea of the film itself about a man who whole-heartedly believes in the security of the salary man’s job. Such a question is:

“Why must a dream [job] have to be something like opening a bakery shop or composing a song? How come dreaming to become rich and to be financially secured, from having the salary man job, is not a dream?”

The question raised by Pun is relevant to the way many Thai white-collar workers think about their dream job (ngan nai fun). Perhaps like in any other country, in Thailand getting a job as a salary man in a company with a high-rise building has become an ordinary life-pattern for many Thais, particularly those who grow up in urban areas or those who have a university degree. However, in the actual realm of office life, not everyone will become successful. In many offices, there are many of those nine-to-five workers who get stuck in the same position and who feel hopeless with their lives that have to depend on a monthly payment and the bonus at the end of the year. In Super Salaryman, we can see this sentiment being dramatised through the character of Nun, the finance manager. When Nun’s female colleagues find out that she has minimal savings and is depressed, they encourage her to open up her own business, claiming that it would free her from the financial burden. A similar case of idealising “being your own boss” as a dream job can also be seen from Nuch, another secretary in the company, who feels jealous when she sees her friends open up their own clothing shops on Facebook.

The prospect of running your own business, being your own boss, and gaining freedom from the life of the salary man, might sound promising. Yet, in reality, not everyone and not every self-owned business can actually succeed. Last year, I had a chance to talk to one of my senior friends who was a manager at the debt-management department of one of the banks in Chiang Mai. She explained that many shops on Nimmanhemin road, a trendy area in Chiang Mai, had to be closed down every year because they could not cope with their debt re-payments. My point here is that dreaming to become your own boss, from running your own business or having an independent career, has been romanticised by many Thai white-collar workers who believe it can bring them a healthier future. In reality, being your own boss is also likely to come with a higher risk than being a salary man in a company that can provide a stable income and health insurance (but of course, according to the capitalist logic, if one wants to be very secureтФА they need to work hard). By saying this, I don’t mean we should all submit and conform to the salary man’s life. Nor do I want to claim that being a salary man, struggling in the office, is the best way to succeed and to be happy. Rather, I want to point out that, as another senior colleague of mine always said to me: in every choice you make in life, there is always a cost to pay. Hence, in the film Super Salaryman, the explanation that Pun gives to his fiancée about the security in life from being a salary man, from the perspective of someone who accepts and tries to be at the top of the structure, is reasonably realistic. He deserves no accusation from anyone at all that he has no dream. His dream, indeed, is to be financially secured.

Overall, despite being a comedy drama, Super Salaryman has successfully distinguished itself from the rest of the white-collar movie genre. The film offers a realistic experience of what can happen in one of the high-rise buildings in Thailand. And without being biased about the salary man’s life, the film also fruitfully addresses the accusation that the salary man has no dreams.

Pasoot Lasuka is a PhD student aIN School of Culture History and Language, College of Asia and the Pacific, the Australian National University. His PhD project is on contemporary Thai cinema.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss