Timor-Leste has terminated one of its maritime treaties with Australia in a bid to find common ground over the disputed Greater Sunrise gas field. But will the move backfire? Rebecca Strating assesses the chances of a resolution to the long-running boundary disagreement.

In early January, Timor-Leste notified Australia that it wished to terminate the 2006 Treaty on Certain Maritime Arrangements in the Timor Sea (CMATS).

The CMATS was designed to establish a framework for the joint development of the contested Greater Sunrise gas field. Both states claim an interest in Greater Sunrise, at one time estimated to be worth US$40 billion.

The termination was followed two weeks later by the announcement that Timor-Leste would scrap two international legal proceedings against Australia.

These latest actions should be interpreted as part of a package of so-called ‘confidence building measures’ that have emerged from the United Nations Compulsory Conciliation (UNCC) meetings held in Singapore.

In April 2015, Timor-Leste initiated the UNCC proceedings under Annex V of United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) to assist in resolving the long-running dispute.

The problem of maritime boundaries

The CMATS placed a moratorium on permanent boundary maritime delimitation.

But over recent years, Timor-Leste’s government has reinvigorated its pursuit of permanent maritime boundaries, arguing that they are necessary for completing sovereignty.

The UNCC process obliged a reluctant Australia to participate in new boundary discussions.

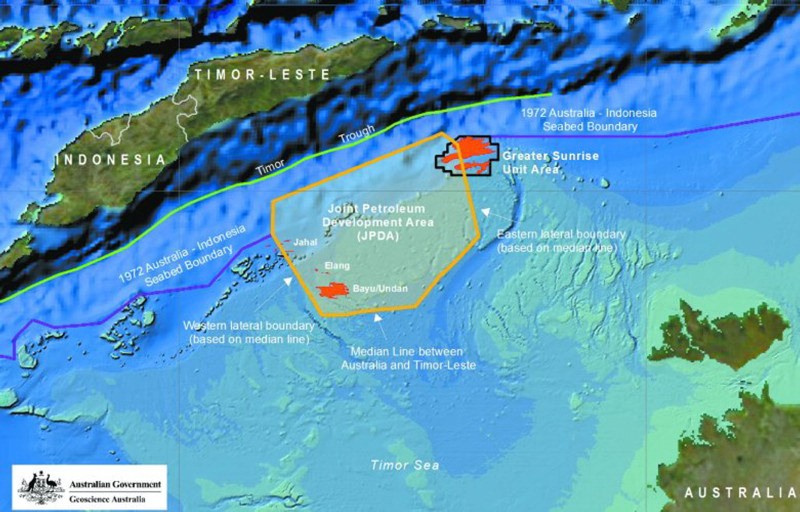

When it comes the boundary, Australia favours principles of ‘natural prolongation’, which provides it seabed territory extending to the Timor Trough. In contrast, Timor-Leste favours a ‘median’ line, which is supported by contemporary international maritime law (see figure one below).

However, the key boundary for establishing possession of Greater Sunrise is the eastern lateral. As shown in figure one, the eastern lateral line that splits Greater Sunrise is drawn according to median line principles.

Timor-Leste, however, claims that the eastern lateral boundary should be located substantially to the east, allowing it to take possession of Greater Sunrise.

Both states have relevant arguments about the rightful ownership of Greater Sunrise, but UNCLOS provides little guidance on the placement of the eastern lateral beyond demands for equity.

Scrapping the legal proceedings

In April 2013, Timor-Leste instituted arbitral proceedings against Australia under the Timor Sea Treaty. The aim was to invalidate the CMATS on the grounds that Australia’s alleged spying in 2004 – which saw an East Timor cabinet meeting over the negotiations bugged — contravened the Vienna Convention of the Law of Treaties.

While the CMATS provided for its own cancellation if an agreement on Sunrise development could not be reached, Timor-Leste was concerned that unilaterally withdrawing from the CMATS would also terminate the Timor Sea Treaty, which currently governs the Joint Petroleum Development Area (JDPA).

As part of the UNCC process, Timor-Leste sought and received assurances that Australia would not seek to dissolve the Timor Sea Treaty if the CMATS was terminated.

The decision to scrap the CMATS has effectively made the spying case redundant.

The second relevant proceeding related to the taxation of the petroleum exported from the JPDA and was also initiated under the Timor Sea Treaty.

Timor-Leste could have continued with its legal pursuit for a greater share of taxes. The decision to drop this case was likely a quid pro quo for Australia agreeing to retain the terms of the Timor Sea Treaty.

Where to from here?

How the dispute will play out in the future will hinge upon whether Timor-Leste is prepared to negotiate a boundary that does not give it all of Greater Sunrise.

Timor-Leste’s shift towards permanent maritime boundaries was motivated by its economic plan to build an export pipeline from Greater Sunrise to its south coast and establish an oil processing industry.

Between 2008 and 2010, the states attempted to agree upon the best ways to develop Greater Sunrise. The licensee consortium, headed by Australian company Woodside, deemed a floating LNG platform to be the best commercial option. Australia ultimately supported Woodside’s decision.

Timor-Leste’s government decided to renew permanent maritime boundaries arguments only after the pipeline talks reached a dead-end.

The subtle differences between the aims of securing permanent boundaries and gaining Greater Sunrise are crucial. A key question for negotiations is whether Timor-Leste would be satisfied with permanent maritime boundaries that would only give it part of Greater Sunrise, or whether it will ‘go for broke’ and refuse to settle for anything less than all (or most) of Greater Sunrise.

The UNCC process has limitations as a form of conflict resolution. First, the report will not be binding on either party. The UNCC is not a court or an arbitral tribunal: it was established under UNCLOS to assist states to reach an amicable settlement of relevant disputes.

Second, while Australia has an obligation to negotiate with Timor-Leste in ‘good faith’ on maritime boundaries under UNCC, and pursue negotiations as far as possible, it does not have an obligation to reach an agreement based on the report.

Terminating the CMATS has made it more difficult for Australia to simultaneously avoid boundary discussions while defending the primacy of the ‘rules-based order’ in maritime dispute resolution. Timor-Leste might be able to pressure Australia to agree to third party arbitration if negotiations fail.

But this is a significant gamble for Timor-Leste. Historically, Australia has preferred negotiating its maritime boundaries.

More problematically is the time it takes to settle cases in international courts.

Oil dependent Timor-Leste has until around 2021 before the oil from the JDPA is depleted – around four years from now. One legal expert suggests it could take seven years for a decision in the International Court of Justice. In the meantime, Timor-Leste’s governments would have to rely upon the $16 billion sovereign wealth fund to furnish states budgets, 95 per cent of which comes from oil revenues. Current independent forecasts have the fund running out before 2027.

The other complication is the potential for Indonesia to become involved. Any court case on the eastern lateral boundary would inevitably require Indonesia’s participation. Greater Sunrise may be closer to Timor-Leste than Australia – but it is also closer to Indonesia. The prospect of Indonesia’s involvement is not in the interests of either Australia or Timor-Leste.

The most pragmatic course of action is for Australia and Timor-Leste to compromise through bilateral negotiations. Australia is reluctant to move on the natural prolongation principle for fear that Indonesia would attempt to ‘unscramble’ its maritime boundaries. However, it also has an interest in Timor-Leste avoiding economic collapse. Any negotiated boundary settlement would likely be based on median line principles.

But crucially, Timor-Leste would need to compromise on the eastern lateral boundary. It seems highly unlikely that Australia would permit Timor-Leste to take all of Greater Sunrise, particularly given the line is already drawn to simplified equidistance.

In the end, the central issue is not whether boundaries should be delineated, but where. A resolution could still be a long way off.

Dr Rebecca Strating is a lecturer of Politics at La Trobe University. She teaches and researches Southeast Asian politics and international relations.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss