Sufi Poetry

Islamic mystical poetry, also called Sufi poetry, is one of the best-known forms of Islamic literature. The works of Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī (1207 – 1273) are among the most popular poems in history, and the influence of Sufi literature on Persian, Indian, and Southeast Asian Islamic writing has been profound. Sufi poetry is admired for its beauty and for its exploration of mystical experience through metaphor. This kind of literature is most closely associated with the Persian language, but Sufi poetry also flourished in Arabic, Turkish, and, as we will see in this article, Malay.

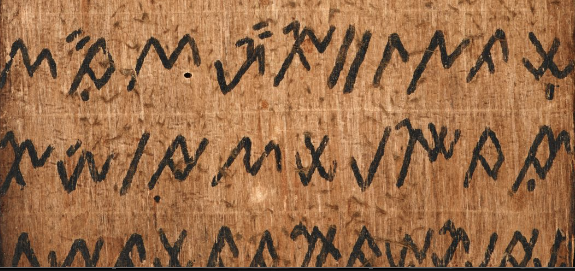

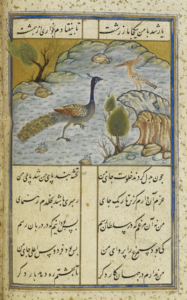

An illustrated 15th- or 16th-century manuscript copy of the Sufi poem The Conference of the Birds by Farīd al-Dīn ‘Aṭṭār (ca. 1145 – 1220), f. 30v. Add MS 7735. (Photo: British Library)

Sufi poetry exhibits a number of key concerns and images that reflect its mystical orientation. Its major theme is the direct spiritual encounter with God, in which the individual’s ego is annihilated (fanā’) as it achieves union (waṣil) with the permanence (baqā’) of the divine. There are conventional poetic metaphors to express being in the state of mystical union: being a drop of water in the ocean, being in love, and being intoxicated.

The precise nature of this mystical union has been a source of disagreement among Muslims, particularly between the followers of the Sufi philosopher Ibn ‘Arabī (1165 – 1240) and his orthodox detractors. Poets like Rūmī expressed, in an artistic manner, a view resembling ‘Arabī’s doctrine of the Unity of Being: roughly speaking, the view that existence is a property belonging only to God, and so God is present in all Creation. According to ‘Arabī, created beings do not have existence in their own right, but reflect the existence of God like a mirror reflects light.

For the Sufi poets, mystic union is the process of recognising that God is within the soul; thus, union with God is the recognition of unity with God. This recognition is the essential theme of the work of a Sumatran Sufi whom many consider to be the greatest poet in the classical Malay tradition: Hamzah of Barus (in Arabic, Ḥamza al-Fanṣūrī).

Hamzah the Sufi Master

Hamzah’s biography is not known in any great detail. It is clear that he was active as a poet and a religious leader around the late 16th and early 17th centuries, and that he came from the town of Barus on the west coast of Sumatra. Barus was a port town that was well-connected to the Indian Ocean trading routes; it was world-famous for the high-quality camphor it exported. Hamzah is largely known from his literary output, which includes just over thirty poems and a number of prose treatises on mysticism. He had a transformative impact on Malay literature; according to the literary critic Vladimir Braginsky:

It is Hamzah who was the first poet to challenge the anonymity of Malay literature, who introduced the main genre of its classical verse, syair, who became one of the originators of religio-mystical writings in Malay and of the Malay-Persian literary synthesis, who initiated a poetical school that influenced the entire Sufi poetry of the Malays.

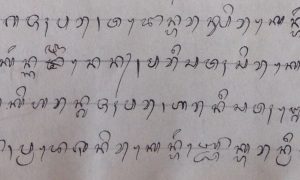

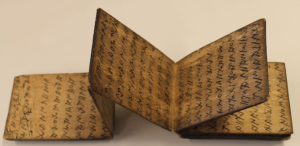

A South Sumatran tree-bark manuscript of the “Poem of the Boat”, a Malay Sufi poem in the tradition of Hamzah; MSS Malay A 2 (Photo: British Library)

Hamzah was regarded as the foremost mystic of his generation. Each of Hamzah’s syair poems ends with an autobiographical stanza, and in several of them he claims to have accomplished the Sufi goal of fanā’; that is, annihilation of the self and a recognition of unity with God. He was a major influence on Syams al-Dīn, who was the official Sufi master to the great Sultan Iskandar Muda of Aceh (reigned 1607 – 1636). After the Sultan’s death, Hamzah’s work became the target of a polemic by the orthodox Gujarati cleric Nūr al-Dīn al-Rānīrī, who argued that Hamzah’s poems were heretical because they implied that humans are of the same nature as God.

The Peculiar Whale

Below is an example of Hamzah’s poetry. The Malay text is based on L.F. Brakel’s edition, posthumously revised and published in 1986 by G.W.J. Drewes. The rather free English translation is mine. I have converted the irregular tetrameter of the Malay into stricter iambic tetrameter in English, but have not followed the repetitive AAAA rhyme scheme of the original. Hamzah’s Malay is dense with Arabic loan words and phrases, which are italicised in the text, and he is renowed for his intricate punning between the two languages.

The poem tells the story of a “peculiar whale” who looks for water in the desert, even though it lives in the sea. The sea is a standard Sufi metaphor for the divine being, while the whale represents the spiritual seeker. Hamzah satirises people who try to find God outside of themselves, such as by pilgrimages to the distant Middle East. In line with the doctrine of Ibn ‘Arabī, Hamzah argues that we are always already at one with God, and our task is to recognise that truth by renouncing worldly distractions and giving up our attachments to ego. The extensive allusiveness of the poetry displays Hamzah’s familiarity with the cosmopolitan worlds of Arabic and Persian literature, as well as a distinctively Southeast Asian perspective on the Sufi experience.

| ‘Ajab sekali akan gajahmina Tempatnya dā’im di laut Cina Mencari air ke Ṭūr Sīnā Olehnya itu kerjanya hina |

The whale is so peculiar! Its place is in the China Sea, And yet it looks for water on Mount Sinai – a wretched task. |

| Laut Cina terlalu dalam Itulah bangsa sekalian ‘ālam Merupakan jān malak dan Ādam Di laut itu kita nin karam |

The China Sea is so profound That all varieties of beings, Including humans, angels, jinns, We all are shipwrecked in that sea. |

| Karangnya banyak rantaunya panjang Teluknya permai seperti kandang Ke laut itu yogya berenang Mangkanya dapat segera memandang |

With many reefs and lengthy coasts, Cute little coves like chicken coops, That sea is where you have to swim, So you can have true sight at last. |

| Ṭawfānnya dā’im terlalu nyala Datangnya sangat tiada berkala Menyelam ke sana sepala-pala Supaya dapat engkau berpahala |

Its typhoons flash incessantly, They can arrive at any time. Submerge yourself there, head to toe, And you will get your just reward. |

| Ādam sūfī diharu shayṭān Di dalam surga berbunga rayḥān Datang ke dunya ke bukit Sailan Mabuk akan Hawa terlalu ḥayrān |

Adam, tormented by the Beast, When paradise was in full bloom, Fell down on a Sri Lankan hill, Confused and fully drunk on Eve. |

| Akan Ādam itu jangan kaughāfil Hikmat Tuhan di sana kāmil Basakan hendak sekalian sā’il Itulah ombak laut yang fāḍil |

Do not ignore what Adam is, God’s wisdom is perfected there, Proffer your questions and requests, He is the tallest ocean wave. |

| Dengarkan hai anak qārī Jangan jauh engkau mencari Daripada air itu jangan kaulari Supaya jadi engkau matahari |

Quran-reciters, listen well: Do not go searching far and wide, Do not avoid the water’s depths, In order to become the sun. |

| Gajahmina terdā’ir-dā’ir Di dalam laut mencari air Laut itu terlalu ẓāhir Pada rupa insān ṣāliḥ dan fājir |

The whale keeps going round and round, To find some water in the sea, And yet the sea is manifest To sinners and to saints alike. |

| Biarkan lashkar dan pawai Lenyapkan arta dan sakai Tark al-dunyā yogya kaurasai Mangkanya dapat tiada kaulalai |

Give up your troops and heraldry, Wipe out your wealth and personnel, You must by choice renounce the world, So you will not miss anything. |

| Beri tahu akan anak patih Jangan sangat engkau beralih Dunya nin seperti parih Manakan dapat kekal kaukasih |

Tell the impressionable youth: Do not be swayed by everything. This world is like a game of dice, How can you go on loving it? |

| Satukan hendak hangat dan dingin Tinggalkan jua loba dan ingin Hancurkan hendak seperti lilin Mangkanya dapat kerjamu licin |

Indifferent both to heat and cold, Abandon greed and craving too, Melt down your will like candle wax, To grease the wheels of all your work. |

| Gajahmina terlalu wāṣil Dengan laut yang tiada berṣāḥil Gila mencari seperti jāhil Olehnya itu kerjanya bāṭil |

The whale, though it already is In union with the shoreless sea, Still searches, mad and ignorant, And all its efforts are in vain. |

| Hamzah Shahrinawi terlalu hapus Seperti kayu sekalian hangus Asalnya laut yang tiada berharus Menjadi kapur di dalam Barus |

Hamzah of Shahrinav is gone, He burned up like a piece of wood, He came in from the tideless sea, He turned to camphor in Barus. |

See part two of this series on Hamzah’s poetry for a detailed commentary on this poem.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss