As Chinese Indonesians head to the polls, safety and justice for past anti-Chinese violence are high on the agenda. Photo credit: dpa Picture Alliance GmbH

If throughout the New Order, Chinese Indonesians were mostly absent from politics, post-Suharto ethnic Chinese are slowly getting over their political trauma and becoming much more vocal. But whom will they vote for and what is at stake for Chinese Indonesians in the upcoming presidential elections?

The ethnic Chinese may only comprise around 1.2% of the Indonesians population (according to the 2010 population census although the actual figure is likely to be much higher), but given their problematic history and socio-economic significance, who they vote for and the reasons behind that choice provide an indication of the kinds of issues that still exist in the country’s racial and minority politics.

While the Jokowi vs Prabowo divide is nation-wide, the issue of whom to vote for this time is particularly important for the ethnic Chinese, not least because of the Prabowo factor. Without a doubt, the most hotly debated election issue for Chinese Indonesians is the on-going uncertainty about Prabowo’s role in the May 1998 riots that affected so many Chinese in Jakarta, Solo, Medan and other cities.

At a recent meeting with a group of Chinese Indonesians at a Bandung restaurant, discussions inevitably lead to the topic of presidential elections and Prabowo’s alleged anti-Chinese past. Visibly exasperated, a few of them questioned how some ethnic Chinese could so easily forget Prabowo’s alleged anti-Chinese past. ‘Everyone knows that he was behind the May ’98 riots, yet they still support him, I just don’t understand the logic,’ said Erik, a small business owner. In agreement, his friend Tata exclaimed, ‘It is our duty to continue demanding for justice, and that’s never going to happen if Prabowo becomes president!’

Throughout the campaign season, I’ve had many similar conversations with ethnic Chinese from all walks of life in Jakarta, Medan, Bandung and other cities. Prabowo’s refusal to clarify his role in the May ’98 riots have lead to assumptions about his guilt, and many Chinese simply do not trust him.

Chatting over cups of tea at a small coffee stall in Medan, my elderly Chinese companion Pak Didi showed me a video on his phone of a speech that Prabowo had made in 2004 to members of Pemuda Panca Marga (Clan Association Youth, a pro-military organisation for the children of Indonesian army veterans).

In the video, Prabowo spoke about the military strategy of ‘looting a burning house’ where he repeatedly said, ‘If someone’s house is on fire, then use the opportunity from the chaos that ensues to loot their house and steal their fortune.’ (you can see this at 1.22) Shaking his head, Pak Didi said, ‘That was exactly what he [Prabowo] did in May ’98 and he won’t hesitate to do the same again in the future. He is more subdued now during the campaign, but who is to know what he and his followers will do to foreigners like us in the future if he becomes president?’

Adding fuel to the fire, support for Prabowo by paramilitary groups such as Pemuda Pancasila (Pancasila Youth) and the Islamic Defenders’ Front (FPI) raised concerns that a Prabowo presidency would give these groups more confidence to terrorise minority groups like the Chinese.

These fears are compounded by recent reports of intimidation by the Prabowo camp, such as recent claims that Village Supervisory Non-Commissioned Officers (Babinsa) had been going door-to-door in residential areas with large ethnic Chinese populations, ‘asking’ the residents to vote for Prabowo.

Newly elected PDI-P Member of Parliament from North Sumatra Sofyan Tan campaigning for Jokowi-JK in Medan. Photo credit: Christine Susanna Tjhin.

To his ethnic Chinese supporters, Jokowi represents hope that Indonesia would not go back to New Order-style oppression. Jokowi’s down-to-earth mannerisms appeal to those who fear a return to autocracy and militarism. Furthermore, Jokowi’s impartial stance on issues of race and religion during his time as Solo Mayor and Jakarta Governor – such as in his insistence on installing Susan Jasmine Zulkifli, a Christian woman, as Sub-district Head (Lurah) in a Muslim-majority area despite FPI opposition – is seen as an encouraging sign of his commitment to pluralism.

However, an equally important issue for the ethnic Chinese is safety. For Chinese Indonesians still traumatised by past anti-Chinese discrimination and violence, choosing the next president is not only about assessing the candidates’ background or history; it is also about voting for the individual perceived most able to ensure the safety of Chinese Indonesians. To many ethnic Chinese, the man considered as ‘stronger’ and better equipped to bring law and order to the country is Prabowo.

Those who support Prabowo argue that there has been no strong evidence proving him to be the mastermind of the May ’98 riots, and that he could well be a political scapegoat in the whole ordeal. Like Ibu Lita, a housewife and Prabowo supporter from the ‘Chinatown’ area of north Jakarta said, ‘I know the rumours about Prabowo, but these days, who knows what to believe anymore? Maybe he was just a soldier who followed orders and took the blame. Wiranto is probably guilty too, and now he’s supporting Jokowi. They are all the same.’

Prabowo defenders also dismiss rumours of Prabowo’s anti-Chinese sentiment by saying that it was Prabowo who supported Basuki Tjahaja Purnama’s (Ahok) candidature as Vice-Governor of Jakarta and point to Ahok’s prominent position in Gerindra.

As can be expected, there are frequent passionate debates between ethnic Chinese supporters of Jokowi and Prabowo. Those who support Jokowi accuse Prabowo supporters of historical amnesia, while Prabowo supporters contend that Jokowi fans only think with their hearts and not with their heads. However, while many Chinese Indonesians have made their choice, there are also many who are still undecided.

Both the Jokowi and Prabowo camps seem to understand the importance of appealing to ethnic Chinese communities, if not to garner physical votes or financial support, then for the public relations boost aimed at demonstrating the candidates’ multicultural and human rights credentials.

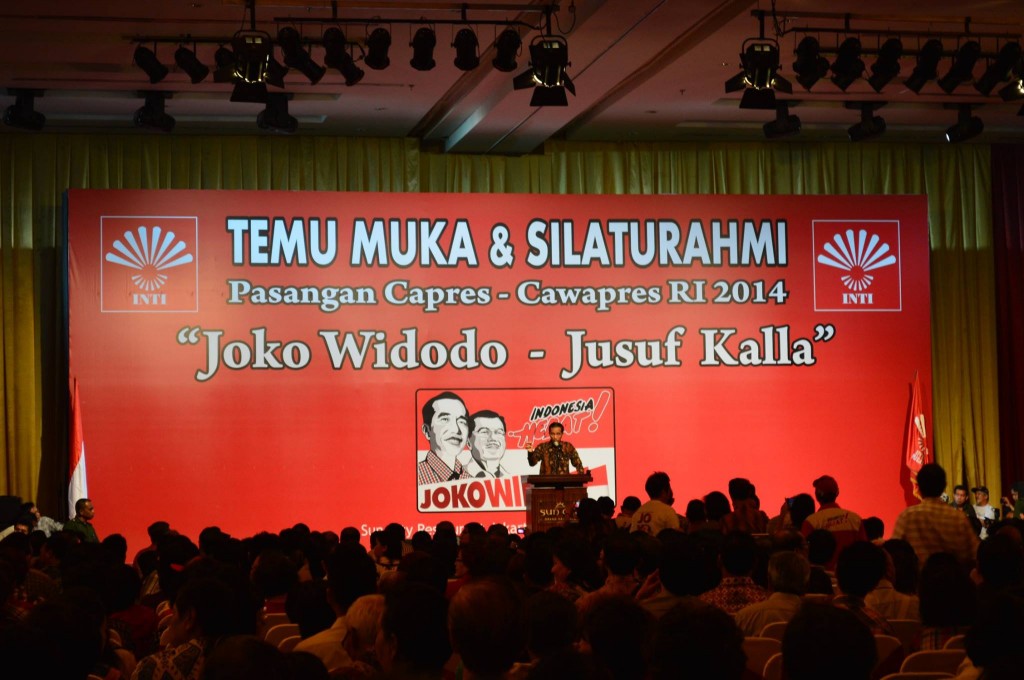

Presidential hopeful Jokowi speaking to a large audience from the Chinese Indonesian Association (INTI) on 26 June 2014 in Jakarta. Photo credit: Charlotte Setijadi

During separate ‘meet and greet’ events with the Chinese Indonesian Association (INTI) I attended in June, both Jokowi and Prabowo did their best to assure the mostly ethnic Chinese audience of their safety and continued wellbeing in Indonesia. Prabowo nostalgically recounted his old friendships with ethnic Chinese friends and even told stories of his fondness for ancient Chinese folklore. Unsurprisingly, both candidates whipped out the ‘Ahok card.’ Jokowi cited his successful partnership with Ahok in Jakarta as proof of his ability to work harmoniously with an ethnic Chinese. Prabowo claimed that he had put himself on the line to guarantee Ahok’s candidature as Jakarta Vice-Governor in 2012.

Nevertheless, while both Jokowi and Prabowo try to appeal to ethnic Chinese voters, they have to at the same time be careful not to look too Chinese-friendly. Anti-Chinese sentiment in Indonesia is still very much alive, despite over fifteen years of reformasi. Recent ‘black’ campaign in social media and publications by hard-line Muslim and anti-Jokowi groups such as Tabloid Obor Rakyat accused Jokowi of not only being a Christian, but also an ethnic Chinese. Very quickly, Jokowi supporters came to his defence and refuted these accusations. However, the very fact that Jokowi supporters felt the need to ‘defend’ Jokowi from accusations of being Chinese (and Christian) is in itself a very sad indication of the state of plural society in Indonesia.

Be close but not too close. Prabowo points to his alliance with Acting Jakarta Governor as evidence he has no anti-Chinese sentiments. Photo credit: Harian 24.

It is impossible to accurately predict which direction the ethnic Chinese vote will sway. My observations suggest that most ethnic Chinese in urban areas are pro-Jokowi, but as is the case elsewhere in Indonesia, it will be a close call in Chinese communities too.

Chinese Indonesians are heterogeneous, and there is no such thing as a unified Chinese vote. One thing for sure is that many Chinese Indonesians will vote for a candidate that can make them feel safe in a country that they love but has so often turned against them. As the presidential race enters its last days, both Jokowi and Prabowo must convince ethnic Chinese voters of their firm commitment to uphold the law and minority rights.

Charlotte Setijadi is a postdoctoral fellow at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. She researches Chinese Indonesian identity politics and China-Indonesia bilateral relations.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss