Like many other oligarchs and businesses exploiting natural resources, mining companies and their elite supporters have a lot of political clout in post-authoritarian Indonesia. This can be seen in the way mining companies have entrenched their influence in local politics, thanks to the significant role they play in financing aspiring candidates in recourse-rich regions.

One of these resource-rich regions, East Kalimantan province, is a major centre of various extractive industries, ranging from oil and gas, timber logging, and more recently coal mining and oil palm. Consequently, it has also become one of the major battlegrounds for mining industry-influenced political contestation. In East Kalimantan alone, there are 1,404 mining licenses registered by the provincial government. Leading local politicians, such as Said Amin, and the notoriously corrupt former district head (bupati) of Kutai Kartanegara, Rita Widyasari, either own or receive kickbacks from mining operations. It’s not surprising that there is a lack of responsiveness from the local government regarding the destructive socio-ecological impacts of mining, including in the gubernatorial election last year.

Extractive business interests and local elites have formed collusive relationships at the expense of rural citizens in Kalimantan provinces. In the neighbouring Central Kalimantan province, the expansion of corrupt land deals and oil palm plantation has seen local political elites enrich themselves, dominate local politics, and suppress dissenting voices who express concern over the destructive socio-ecological impacts of natural resource exploitation. In East Kalimantan, the development of the coal mining industry has brought devastating impacts for rural livelihoods and bred corruption. Such a practices are representative of broader patterns of how oligarchic competition for political offices, and the collusive relationships with business that are prevalent among local elites, influences the trajectory of post-authoritarian local politics.

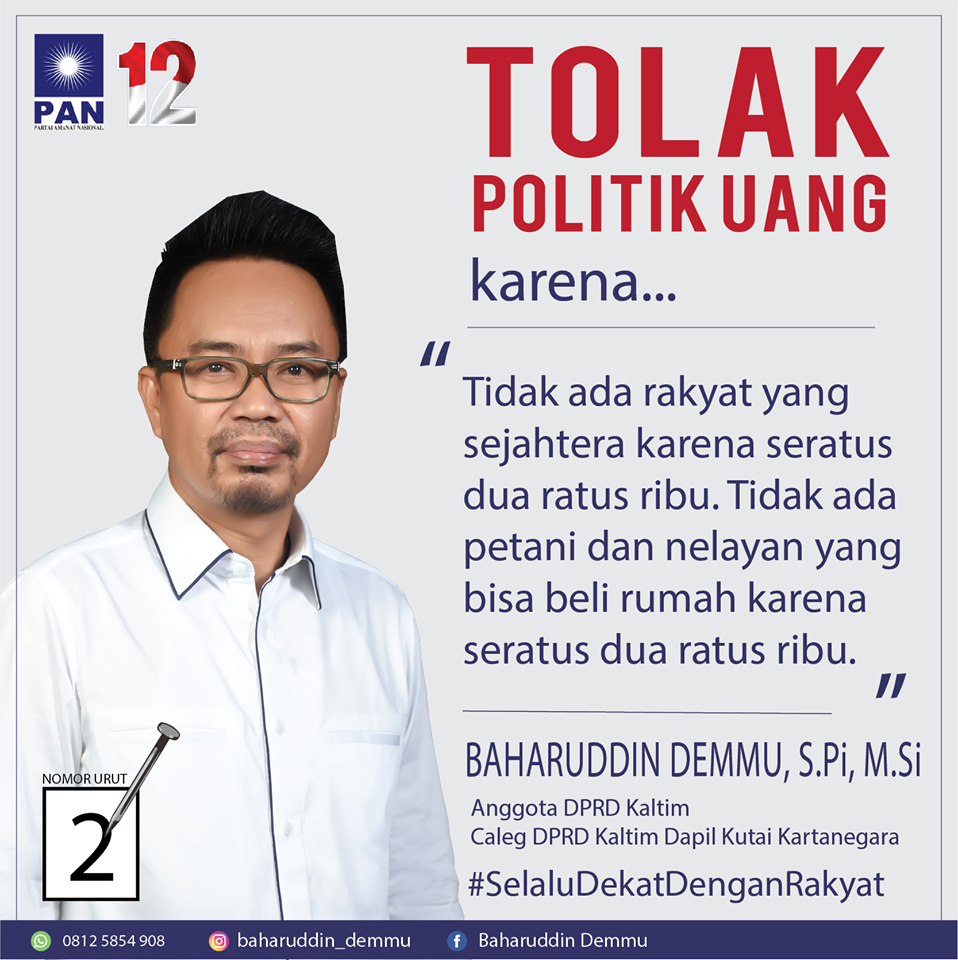

But in the 2019 election campaign, some Indonesian politicians in Kalimantan are trying to speak out against the excesses of the extractive industries there. In Samarinda, East Kalimantan, Baharuddin Demmu (Bahar), a National Mandate Party (PAN) member of the provincial parliament, is a rare example of an activist-turned-politician who continues to criticise extractive business interests and their local elite allies even after joining the local parliament. I spent a week observing Bahar and a number of activists and community members in the 2019 legislative election campaign to try to understand how mining influences electoral politics in East Kalimantan, and the challenges an activist-turned-politician faces in campaigning on a platform of environmental sustainability.

Checking the excesses of coal mining industry in the provincial parliament remains hugely difficult, reflecting the continuing dominance of local predatory interests that benefit from the industry, and the limited influence that rural citizens and their civil society allies have in defending the sustainability of rural livelihoods. In this context, Bahar’s story is important because it shows how a politician in a resource-rich province is trying to advocate for the rights of communities that have been affected by large resource extractive industries, and rural constituencies more generally. It tells us that there are Indonesian politicians who do care about their voters. But challenging mining-fuelled oligarchic interests, and promoting environmental sustainability and rural livelihoods, requires a much more extensive effort by rural lower-classes and their civil society allies— work that cannot rely on one politician alone.

Baharuddin Demu campaign ad calling on voters to “reject money politics”. (Photo: Instagram)

The rise of an unlikely politician

Bahar had a first-hand experience of how extractive industries damage the environment and rural livelihoods. During his childhood, Chevron, a multinational oil and gas company, evicted his family from their house and farm with the help of local military forces back in 1986. This experience influenced him to get involved in community activism during his college days. He then joined the East Kalimantan branch of the Mining Advocacy Network (JATAM), a mining watchdog organisation, and led the organisation as its coordinator from 2002 to 2004.

Inspired by his experience serving as an elected village head from 2006 to 2009, Bahar decided to run for a seat as an MP. In his first attempt, he won a seat in the district parliament of Kutai Kartanegara in 2009. In the parliament, he continued to voice his bold opposition against unethical corporate practices by the mining industry, a move that upset many other politicians who benefitted from coal mining. After winning a seat in the provincial parliament, he remained committed to voice his opposition to the excesses of coal mining, where he was a strident critic of the mining industry’s social and environmental failings.

Bahar’s successful foray into politics shows how a politician with an activist background can try to make a difference at the local level. However, just getting there isn’t enough: Bahar, like so many activists-turned-politicians, still faces significant challenges in fighting big extractive industry companies from within the system.

How mining influences politics in East Kalimantan

John Sidel has argued that quality of local democracy is suppressed in areas where “control over the commanding heights” of the local economy are dominated by few powerful players. This is true in East Kalimantan, where the extractive sector dominates the local economy. Access to mining money encourages politicians to outspend each other in election campaigns, and the resulting increase in the cost of campaign financing makes it more difficult for cash-strapped candidates to make inroads into local politics.

Given the high cost of election campaigning in Indonesia, political hopefuls with weak ties to voters have no choice but to rely on campaign financing from supportive donors. According to a 2018 study from the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK), many candidates competing in the 2015 executive head elections (known as Pilkada) needed external sources for campaign financing. The study also found that around 43% of the candidates who lost their elections spent around Rp1–5 billion (A$100,000–500,000) on their campaign. Those who won their elections, meanwhile, needed around Rp20–30 billion (A$2–3 million) to win a mayor or district head post, and up to Rp100 billion (A$10 million) to secure a gubernatorial seat.

Further research by JATAM has shown that candidates often strike shady deals with mining companies to win local elections in resource areas. The companies will fund their campaign and in exchange receive mining licences once the candidates of their choice win the elections. For instance, after the 2010 pilkada, the number of mining licences increased significantly in various resource-rich districts, including Kutai Kartanegara district. This trend continued until very recently, in the 2018 executive head elections. In total, JATAM and a number of other civil society organisations estimate that the number of mining licenses issued across Indonesia exploded from 750 licenses in 2001 to 10,000 in 2010.

In such a high-cost political arena, it is difficult for someone like Bahar to win election. However, he has attempted to compensate for his lack of campaign funds with his strong ties to local communities. His activism and familiarity with the rural context have become his strongest political assets. Activists and community members that I talked to confirm this assessment: according to them, to win a seat in East Kalimantan, one has to have either a strong connection with the voters or a huge amount of money to buy votes. Bahar has the former, so he does not really need the latter. Bahar claims that he only needed to spend Rp20–30 million (A$2,000–3,000) for his campaign to secure a seat in the district parliament and Rp100-200 million (A$10,000–$20,000) for his campaign for a seat in the provincial parliament. If true, these figures are significantly lower than the figures a successful politician is usually required to spend.

As an incumbent, though, Bahar also maintains the loyalty of his constituencies by facilitating their access to state resources and facilities. “If local peasants and fishers do not have their groups yet, then I will help them out (to make one),” he said. Bahar’s colleague, Syarifuddin, another politician from PAN, told me, “it is important for our constituencies to have their own peasants’ and fishers’ groups, otherwise it will be difficult for them to submit proposals for facilities and the like,” he added. Bahar and my interlocutors claimed that by using tactics like this Bahar does not have to buy votes.

Bahar and his supporters are quite optimistic that he will win the re-election for his second term in the provincial parliament. But the more crucial question is what he will do to fight against mining-fuelled oligarchic interests in East Kalimantan and for the betterment of his constituency. Bahar and his activist colleagues are well aware that oligarchs continue to dominate the electoral arena in Indonesia. As Merah explained it to me, “he needs to fight oligarchic interests not only from outside but also from inside (his party).”

This is a herculean task. Bahar told me about his experience of receiving “advice” from several people to tone down his criticisms of the coal mining industry. “I received phone calls [from an unknown person] advising me to stop criticising mining…when I was in Jakarta a few people also came to me and told me to stop the investigation [of illegal mining] in the provincial parliament,” he told me. “Nevertheless, I carried on,” he added.

What makes it challenging is the fact that national-level oligarchs have a vested interest in keeping and expanding coal mining businesses in East Kalimantan. A new investigation by Global Witness, an environmental watchdog organisation, has revealed that figures such as Luhut Pandjaitan, a former general and close advisor to Joko Widodo, and Sandiaga Uno, Prabowo Subianto’s vice-presidential candidate, are significant beneficiaries of coal mining in East Kalimantan. Given their extensive political influence, one might question how individual activists can withstand the influence of national oligarchs in their regions.

Mining in East Kalimantan (Photo: Ray Yen)

How much change can be won through elections?

Moreover, Bahar has not been able to break free from the common practice in Indonesian politics of building patronage networks. It is true that he neither buys votes nor distributes small gifts to a group of favoured voters, but he has not been able to transform the dependent relationship between him and his voters. Recall his admission of facilitating the creation of local peasants’ and fishers’ groups to access state resources and facilities in his constituencies. While this helps the voters to some extent, it also precludes the possibility of a more independent and equal relationship between voters and politicians.

What is equally important is that marginalised rural communities and civil society actors in East Kalimantan and other resource-rich province do not fall for the illusion that electing an MP that represents their interests will solve the many problems caused by coal mining and other extractive industries for once and all. Historical examples have shown that it is the disruptive actions of lower-class and civil society movements that led to major political transformations such as democratisation. This is also true at the local scale, including in East Kalimantan: without consistent mass pressure from rural citizens and their civil society allies, it would be difficult to ensure that the many problems associated with resource extraction are heard and accommodated in local and national politics.

When asked about what he thought of Bahar’s strategy of entering electoral politics, Merah Johansyah Ismail (Merah), the national coordinator of JATAM, said, “sometimes he repeats the (dominant) discourse (that working within the system should be the main strategy). But we still respect and maintain our communication with him.” I asked Merah what the main strategy for advocating for the rights of communities affected by mining should be. He replied, “we have no choice but to promote and rely on mass actions.” Merah’s assessment is quite accurate: major social movements in the 20th century such as workers’ and civil rights movements were able to force elites to make some policy concessions through mass actions such as protests and demonstrations.

The gold farmers

Nancy Lee Peluso on the promise and perils of small-scale illegal mining in West Kalimantan.

In other words, a more concerted two-pronged strategy—which involves activists entering electoral politics as well as the intensification of contentious collective actions from below—is needed to substantially improve the quality of democracy in East Kalimantan. Bahar is no Tony Benn (the militant Labour Party politician who remained committed to, and a participant in, lower-class mobilisation while he was in office). But he can learn from his own experience—some of Bahar’s voters are the ones who joined him in mass demonstrations against the oil and gas industry’s lack of attention to people’s livelihoods back in his activist days. These protesters are also the ones who broadened the local democratic space enough to allowed him to win a seat as an MP. Without these disruptive actions, it would be difficult for ordinary citizens to get their voice heard and make a difference in local politics, even under democratised and decentralised settings.

Nevertheless, Bahar’s unusual track record has shown how there is a possibility for a more meaningful local democracy in Indonesia beyond illiberal populism or oligarchic hegemony. Unfortunately, such an example remains few and far between. In a sense, Bahar’s rise is an exception that proves the rule: that oligarchs and their local supporters still dominate Indonesian local electoral politics.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss