Elections in Southeast Asia occur in a wide spectrum of regimes, with varying degrees of political freedoms. The one-party states of Viet Nam and Lao PDR hold national elections with some degree of (intra-party) competition. The electoral autocracies in Singapore, Malaysia, and Cambodia – some more hegemonic, some more competitive – call to the polls with varying degrees of contestation. Elections in the Philippines have a history of more than 100 years, while Myanmar is just emerging from some decades of dictatorship. Indonesia and Timor-Leste seem to be on a remarkable and fast trajectory towards liberal democracy, while Thailand – after what now seems as an interim period of electoral democracy – has slid back into dictatorship once more. Finally, Brunei is one of only five states globally that does not provide for any representative national election to the legislature at all.[1]

The meaning of elections varies considerably in such a diverse group of countries, not least due to the fact that some elections provide more choices than others. But are there any common trends discernible among Southeast Asian countries?

The expert survey on ‘Perceptions of Electoral Integrity’

The Electoral Integrity Project based at Harvard and Sydney Universities has just released a new report and dataset for The Year in Elections 2014 that can help answer that question.

Expert assessments evaluate the state of the world’s elections each year. The third release of the Perceptions of Electoral Integrity (PEI) data-set covers 127 national parliamentary and presidential contests held from 1 July 2012 to 31 December 2014 in 107 countries worldwide. More elections will be evaluated as they are held in future years.

Evidence is gathered from a global survey of 1,429 domestic and international election experts (with a response rate of 29%). Immediately after each contest, the quality of each election is evaluated based on 49 indicators. Responses are clustered into eleven stages occurring throughout the electoral cycle and then summed to construct an overall 100-point expert Perception of Electoral Integrity (PEI) index and ranking.

Electoral integrity in Southeast Asia

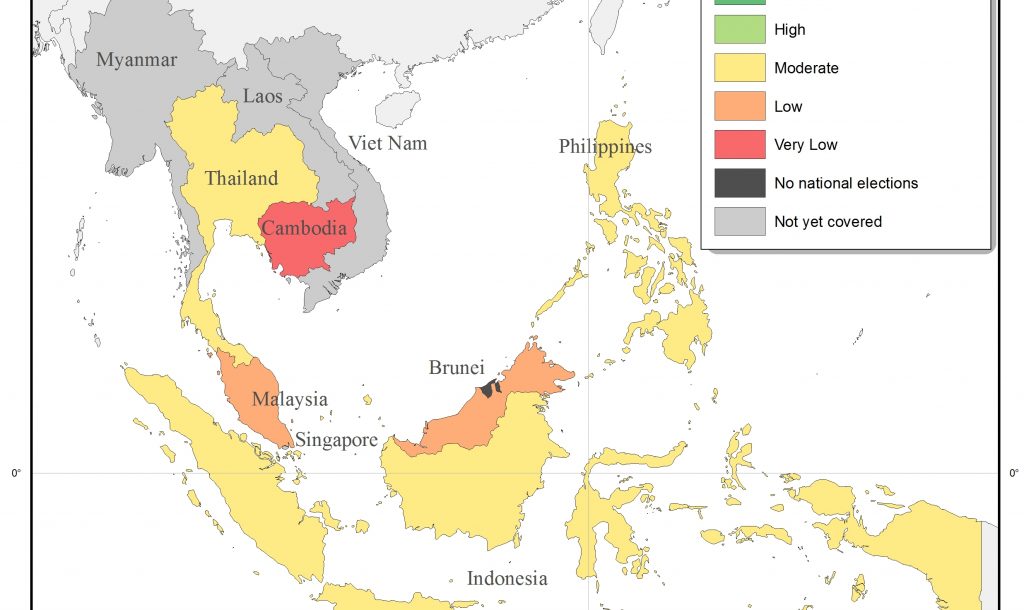

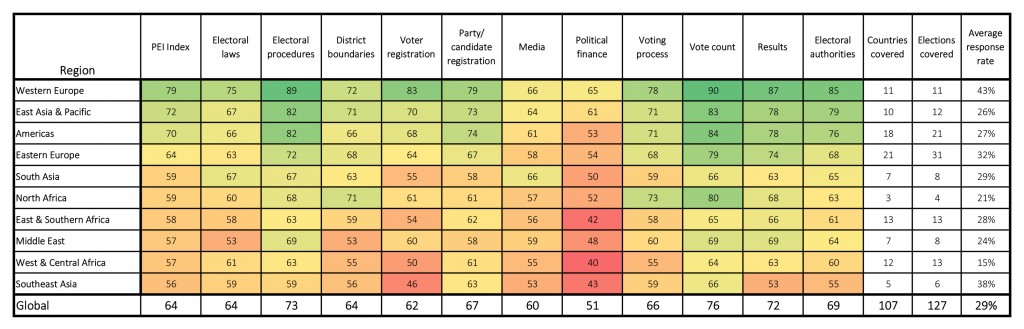

Six Southeast Asian contests were evaluated in the PEI survey in from 2012 to 2014.[2] The striking result is that Southeast Asia performs worse on overall electoral integrity than any other region in the world. The average PEI Index for Southeast Asia is 56 out of 100 (compared to a global average of 64)[3]. This means the region ranks below Western and Central Africa and the Middle East – other places rife with flawed or failed elections. Southeast Asia also scored lowest among all world regions on the sub-indices on electoral procedures (score of 59 compared to global mean of 73), voter registration (Southeast Asia: 46; global mean: 62), media coverage (Southeast Asia: 53; global mean: 60), results (Southeast Asia: 53; global mean: 72), and electoral authorities (Southeast Asia: 55; global mean: 69). Table 1 shows overall levels of electoral integrity of Southeast Asian countries compared to other regions. See here for a global comparison of all elections worldwide.

Table 1: Electoral Integrity by region (2012-2014)

Source: Electoral Integrity Project. 2015. The expert survey of Perceptions of Electoral Integrity, Release 3 (PEI_3.0)

There could of course be several sources of error in these devastating results. With only five countries and six elections in the analysis so far, the stock of data on Southeast Asian elections is not overwhelming. Yet, in a small region like Southeast Asia, the number of observations will necessarily remain lower. The numbers are similar to the other problematic regions (Western & Central Africa, and the Middle East). Furthermore, the regional response rate is in fact above average. The invitation of 232 experts yielded a response rate of 38% – much higher than the global mean of 29%.

It is a possibility that the responding experts are systematically different from experts on other world regions and therefore give skewed answers on the survey. But what gives confidence in the results is the fact that the experts on Southeast Asia did not differ significantly from the global pool of experts in terms of age, gender, familiarity with elections in the country, political views from left to right, or being a domestic or international expert. More importantly, their views on three vignettes – questions about how serious they would rate three hypothetical scenarios of electoral violations – did not differ significantly from the global pool of experts[4]. This essentially means that all the experts use the same yardstick to evaluate electoral integrity.

Finally, it must be noted that this evaluation does not yet include the potentially problematic elections in Myanmar, Viet Nam, or Lao PDR. If anything, the region’s score might be expected to deteriorate even further when these elections are included in future releases of the data.

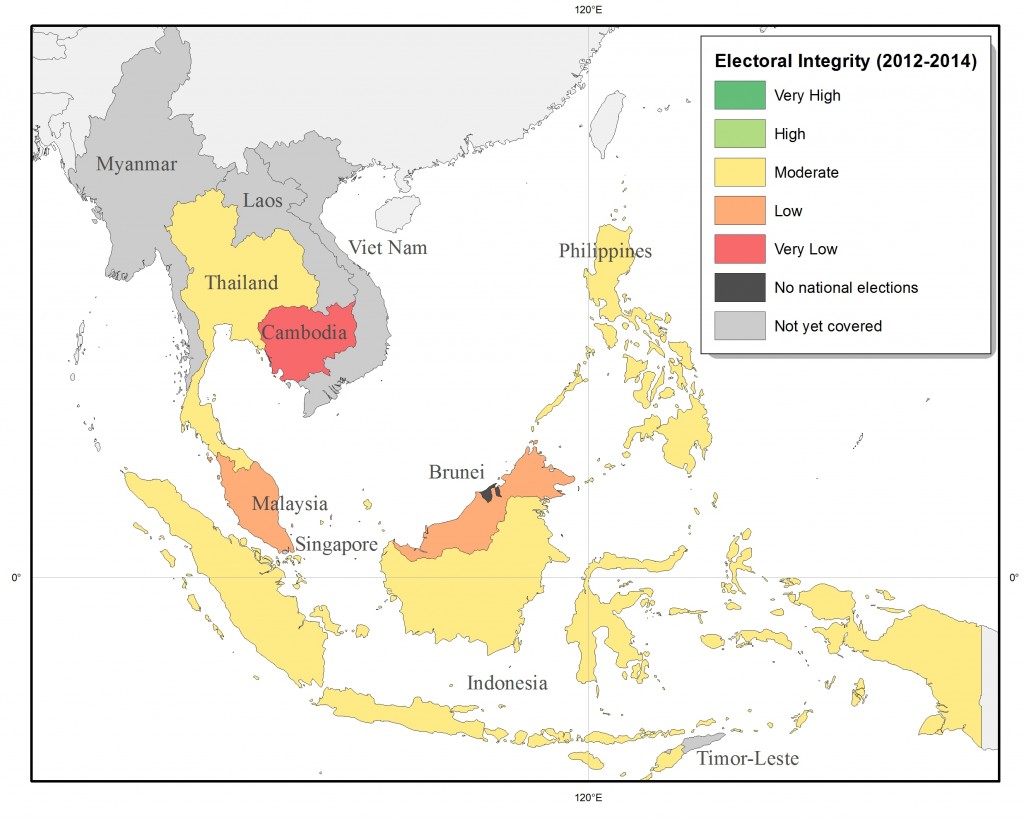

Figure 1: Electoral Integrity in Southeast Asia (2012-2014)

Note: See the full report for an explanation of the countries included in the survey. See here for a dynamic global map of results. The levels of electoral integrity are calculated in terms of standard deviations from the global mean: Very High = >1.5 Std.Dev.; High = 0.5-1.5 Std.Dev.; Moderate = -0.5 – 0.5 Std.Dev.; Low = -1.5 – -0.5 Std. Dev.; Very Low = < – 1.5 Std. Dev.

Source: Electoral Integrity Project. 2015. The expert survey of Perceptions of Electoral Integrity, Release 3 (PEI_3.0)

What is wrong with elections in Southeast Asia?

What specifically caused these devastating expert evaluations? There are stark differences between countries in the region as well as across the different stages of the electoral cycle, as the disaggregated results in Figure 2 show. The contests in Cambodia and Malaysia were evaluated well below the global average across all eleven stages of the electoral cycle, while elections in the Philippines, Thailand and Indonesia show a more nuanced picture.

In the 2013 election in Cambodia, voter registration (score of 30 compared to a global mean of 62) as well as the aggregation and announcement of results (Cambodia: 40; global mean: 72) were flagged as exceptionally poor. Local civil society organizations and the regional watchdog ANFREL called for an independent investigation into alleged election irregularities. The opposition lawmakers boycotted parliament for some time, while anti-government forces staged several large protests over many months, accusing Prime Minister Hun Sen’s Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) of rigging the vote. A negotiated settlement with promises of electoral reform and a power sharing arrangement let the protests subside for now.

The Malaysian contest of May 2013 was evaluated worst on electoral laws (Malaysia: 33; global average: 64) and on the delimitation of voting district boundaries (Malaysia: 28; global average: 64). The score for district boundaries was in fact the lowest out of all countries in the world – followed closely by the US with the second lowest score. The ruling Barisan Nasional (BN) won only 46.5% of the vote but gained a majority of seats (133 or 59.9% of the lower house), which some observers attributed to the malapportionment of voting districts and other irregularities. In particular rural constituencies – traditionally strongholds of the ruling party – are advantaged compared to urban ones. The Bersih 2.0 movement and other electoral reform campaigners staged a people’s tribunal and large scale protests in response. Electoral reform has stalled, perhaps due to the stark polarization of the electorate. It may remain elusive, in particular with opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim incarcerated – a strong blow to the opposition Pakatan Rakyat (PR).

The administration of elections in the Philippines seems to work reasonably well, as the PEI experts rated the country as moderate in most categories of electoral integrity. Yet, political finance (Philippines: 36; global average: 51) and the voting process itself (Philippines: 53; global average: 66) were seen as exceptionally problematic. The latter is especially stunning, given the country’s long history and practice with elections. Yet the use of electronic voting machines has remained a contentious issue in the country, with some criticizing it as a possible loophole for fraud and others lauding them as increasing convenience for voters. The low evaluation of campaign finance coincides with the view that Filipino elections are the playground of political dynasties. Their accountability and legitimacy function is undermined not only by money politics, but also by the palpable disconnect between the electorate and government services of any kind.

Figure 2: Problems during the electoral cycle

Source: Electoral Integrity Project. 2015. The expert survey of Perceptions of Electoral Integrity, Release 3 (PEI_3.0)

Thailand presents a unique case among the observed countries. Its derailed snap election of 2nd February was ranked 88th out of all 127 contests covered by PEI, not least due to the violent disruption campaign of the opposition People’s Democratic Reform Committee (PDRC) and the subsequent disenfranchisement of millions of voters. Yet, the country ranks above the global average in terms of electoral laws (Thailand: 80, global mean: 64) or district boundaries (Thailand: 76; global mean: 64). The 2014 election deepened Thailand’s political crisis – with the constitutional court annulling the contest on 21 March 2014, and the military staging a coup d’état on 22 May 2014, Thailand’s second coup in a decade. International watchdog organizations registered a significant deterioration of the human rights situation in Thailand since the coup.

Elections remain deeply controversial in Thailand. Despite the proliferation of party bans, institutional engineering, and the politicization of courts, popular sentiment seems strongly in favor of electoral democracy, as election results and turnout since 2001 have shown. Yet, there is a non-negligible and politically powerful minority that rejects elections outright. This coalition argues that politicians are corrupt, and voters easily bought and too ignorant to be able to distinguish between good and bad politicians. While making reference to the concept of electoral integrity, this discourse seems not to match well with the evidence collected through the PEI experts’ evaluations. The results of the PEI survey suggest that elections in Thailand are by and large well-administered in the technical aspects. Election fraud, vote buying or other forms of manipulation seem to be less problematic and on par with other countries in the region. The PEI experts identified the opposition movement’s intimidation campaign, and the electoral authorities’ fainthearted enforcement of the law (electoral authorities – Thailand: 47, global mean: 69), as the main problems.[5]

Indonesia held two elections in the period under observation, both of which compared favorably in the region and even globally. In seven out of the eleven stages of the electoral cycle Indonesia achieved the highest score among Southeast Asian countries. The presidential election was ranked 51st in the world, while the legislative polls were ranked slightly worse at 82. This was mainly due to money politics. Independent organization Jaringan Pendidikan Pemilih untuk Rakyat (JPPR) reporting vote buying in over 30% of observed polling places in 25 provinces, and vote brokers with changing loyalties remain instrumental for all political parties to get out the vote. Consequently, political finance was among Indonesia’s worst indicators (Indonesia: 47; global mean: 51).[6] Despite these problems, the General Elections Commission (KPU) was lauded by observers for its increased professionalism.

In the following presidential election of 9 July 2014, the majority of polling institutes called the election for former Jakarta governor Jokowi, based on exit polls and quick counts. Yet, four survey institutes issued quick counts naming general Prabowo as the winner. These polling institutes were found to be aligned with the Prabowo campaign, the conflicting counts allegedly a tactical manipulation of public opinion to buy time to intervene in the official vote count conducted by the KPU. Yet, the maneuver failed, not least because the Indonesian EMB had committed to placing online the scanned images of the official reports from every single polling place. Several crowdsourced quick count initiatives were instrumental in nudging public opinion by confirming Jokowi. Nevertheless, this attempted manipulation resulted in a low score in the results category for Indonesia (Indonesia: 63; global mean: 72).

What’s next?

While positive developments in Thailand’s electoral framework were reversed by the military coup, Indonesia seems the only country on a somewhat stable trajectory towards electoral integrity. Without a doubt, an overall bleak picture of elections in Southeast Asia remains.

Hopefully, upcoming polls will give evidence to the contrary. Elections in Myanmar are expected for November 2015. Since 2010, the country has undergone massive economic liberalization whilst transitioning from a closed military dictatorship to a formally electoral political system. The 2015 polls are seen as a test for the newly built institutions. Yet, the persistent power of the military and state-facilitated crony capitalism are seen to be impediments to the reform process. Various constitutional provisions such as the 25% of seats in the legislature reserved for the military, continued fighting in Kachin and northern Shan States, as well as anti-Muslim violence against Rohingya in Rakhine State also do not increase confidence in the integrity of the polls.

Elections in Viet Nam and Lao PDR – last held in 2011 in both countries – are often dismissed as mere charades. Yet, even without inter-party competition, there is a growing need for the one-party-state to make the elections work better to bolster its legitimacy. Competition between party members – although opaque and delineated along intra-party faction lines – is a possible source of such legitimacy, providing a modest degree of choice for voters. While there is no reason for overt optimism, it is an open question whether or not elections in these countries have less integrity than in the rest of the region.

Timor-Leste held its last election in 2012, with the next one tentatively scheduled for 2017. The 2012 polls were marred by some incidents of violence, but international observers rated it as free and fair over all. Given the comparatively positive ratings by Freedom House and Reporters without Borders, polls in this young island nation may well improve Southeast Asia’s overall score.

Overall, there is much room for improvement. Electoral reform is a perennial item on the agenda in most Southeast Asian nations. Of course, even if elections were conducted according to international standards, delivery of public goods or social justice would be far from ensured. Such governance outcomes do not only depend on equitable participation on the input side (i.e. clean elections), but also on state capacity, horizontal accountability, and the extent of corruption, among other factors.

But if nothing else, the post-election protests in Malaysia and Cambodia, the small but continuous signs of discontent in Thailand, as well as the vibrant civil society efforts to strengthen electoral integrity in the Philippines and Indonesia show that citizens across the region are fiercely protective of their vote. This demand for democracy is currently met with an under-supply. But it does not need to stay that way.

Max Grömping is a PhD candidate with the Electoral Integrity Project at the University of Sydney. His current research focuses on the impact of social media and domestic observers on electoral integrity. Prior to this, he lectured at Thammasat University, Thailand.

Contact: max.groemping[at]sydney.edu.au Twitter: @MaxGroemping

Footnotes

[1] The others are China, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, and Qatar.

[2] These are the Malaysian parliamentary election on 5 May 2013, the Philippines Senate election on 13 May 2013, the Cambodian parliamentary election on 28 July 2013, the annulled Thai parliamentary election on 2 February 2014, the Indonesian legislative election on 9 April 2014, and the Indonesian presidential election on 9 July 2014.

[3] This difference of means is statistically significant at the 0.10 level in a 2-tailed independent sample t-test. Unless otherwise noted, all comparisons of means cited explicitly in this report are significant at the 0.05 level.

[4] Difference-of-means tests on the demographic variables, familiarity with the election, political views, and the three vignettes were all well above the 0.05 p-value. Robustness tests available from author upon request.

[5] It must be noted that the survey results were collected before the Constitutional Court’s annulment of the election. This event and the subsequent coup is therefore not reflected in the experts’ assessments.

[6] Yet, Indonesia did not differ significantly from the global mean in this regard. In fact, campaign finance has been acknowledged as the most problematic area of electoral integrity in global comparison. See the upcoming edited volume on ‘Checkbook Elections’ and the Money, Politics, and Transparency project.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss