Christine Gray explores connections between religion, finance and power in Thailand.

This week’s supermoon marked the end of the kathin season — kathin being an ancient Buddhist ritual that takes place between the full moons of October and November.

During the ceremony, Buddhist laity, emulating the example of the devout Buddhist king, offer robes and other gifts to monks at temples across the land. The ritual marks the end of the rainy season, of monks’ three-month Lenten retreat, and the beginning of the rice harvest. It is also the means by which monks count seniority in the Sangha, the organisation of Buddhist monks.

A well-hidden priority of the Crown Prince in the weeks following the 13 October death of his father, King Bhumibol, performance of kathin rituals at the kingdom’s first-class royal temples likewise creates and re-creates rank within the royal family.

No one performs kathin at a royal temple without His Majesty’s express permission. See notices here and here.

The kingdom’s most splendid royal temples (wat luang) encapsulate the kingdom’s history, or the Chakri Dynasty’s version of that history. Thus kathin performances by top royals are living history, teeming with information about the interregnum and succession. Taking place as they do in a religious format, they have the added advantage of being virtually invisible to farang (foreigners) and the foreign press.

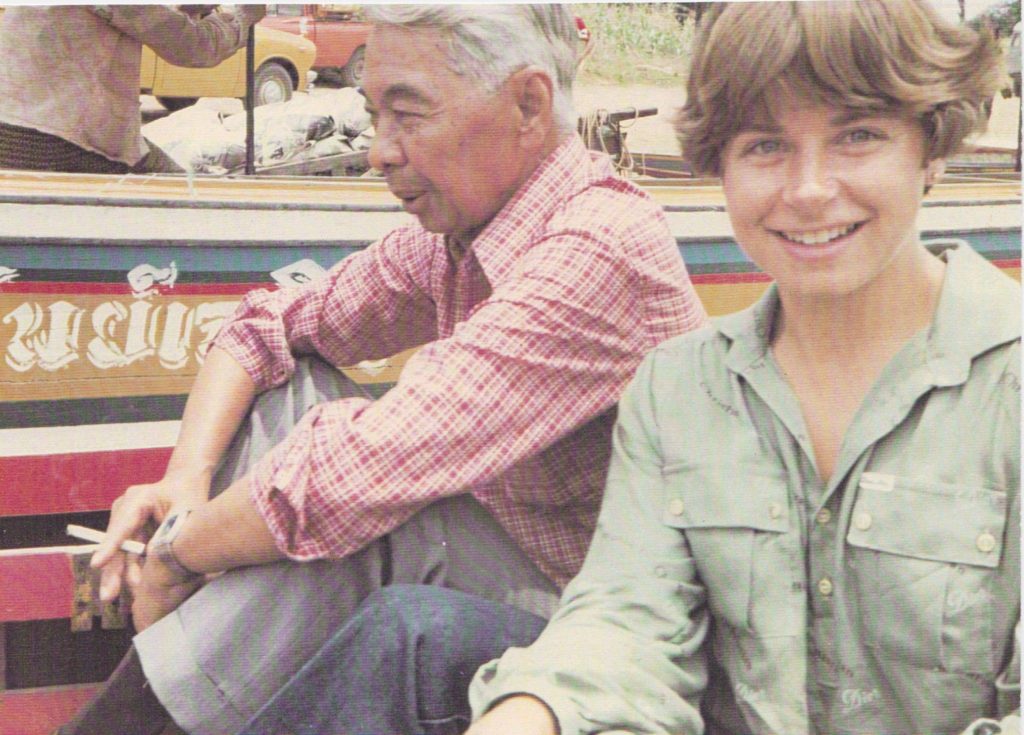

From 1978 to 1980 I was fortunate to gain access to royal kathin as part of doctoral research on kathin rituals and national integration.

Over two ritual seasons, I trailed members of the royal family to kathin luang and kathin phraratchathan, those offered “in the name of the king” (nai nam nai luang), at the foremost royal temples in the land.

The study of kathin in both its royal and non-royal forms took me deep into Isan, the impoverished, rebellious northeast, a main focus of my study.

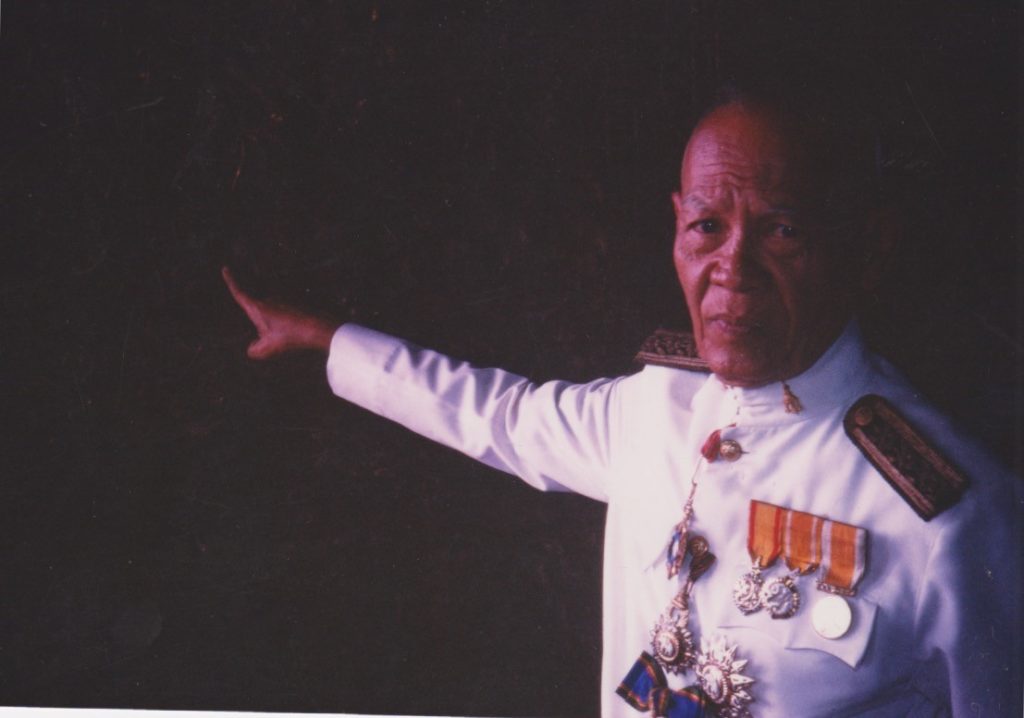

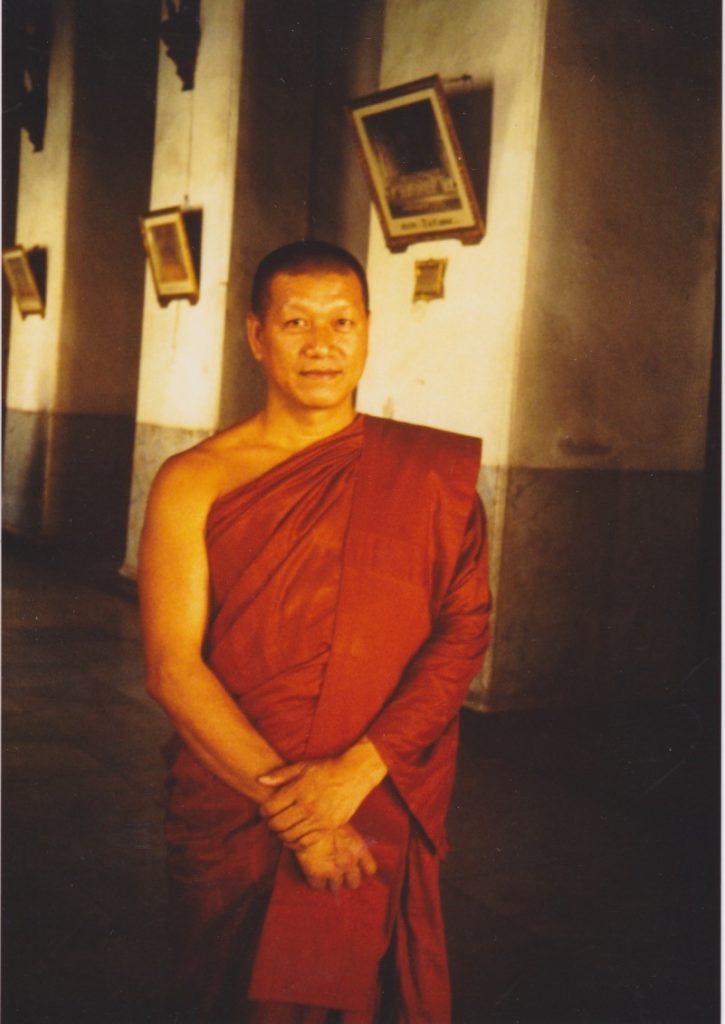

Celestial association enabled me to interview up and down the ritual and social hierarchy: from the fearsome Lord Chamberlain, a former member of the US’ World War II intelligence agency, the OSS, and head of the Crown Property Bureau (about which it was taboo to speak); to longtime Palace retainers, who knew the history of everything; to former Prime Minister MR Seni Pramoj and members of the Democrat Party; to bureaucrats and bankers, senior and junior; to leaders of the socialist movement in the northeast, a major political base of Pridi Phanomyong in the 1930s and 1940s; to a former education minister of the fervent anti-royalist Prime Minister Field Marshal Phibun Songkram (1938-1944, 1948-1957). I also interviewed monks of all ranks and political camps, including the controversial abbot of Wat Bowonniwet.

In the course of my research, I discovered that Bangkok Bank, Ltd was “latching on to the royal virtue” (pheung phraratchaparami), sponsoring kathin at royal temples “in the name of the king” to penetrate rural markets, particularly in the Northeast.

Both the bank, which received the royal garuda, the symbol of royal patronage, in 1967, and its Sino-Thai founder, Chin Sophonpanich, were heavily involved in the narcotics trade as well. His top lieutenants carried the king’s kathin gift to Khon Kaen, not Chin.

Many people, including young bank workers, were concerned about the morality of using religion so blatantly for financial gain.

Furthermore, even if some scholars chose not to, the supposedly unsophisticated people of Isan understood quite well how land changed hands under the dictatorial regimes that distinguished the Ninth Reign of the Chakri Dynasty, just as they understood first-hand the humiliations of the sex trade.

It amazes me still that journalists and scholars refuse to question how the Crown Properties achieved such enormous proportions over the course of the 20th century. How is it that Thailand, such a tiny country, has produced so many billionaires who operate on a global scale, many of whom are designated as “self-made”? How, indeed, did the gentle, modest King Bhumibol, dedicated to the development of his country, become the world’s richest monarch?

When the dissertation was completed many years later, the bank’s connection with royalty and mention of the Crown Property Bureau were not received well by senior scholars. Or any scholars.

“You can’t always believe what they would tell a young girl like you,” huffed a senior anthropologist.

Scholars slightly older than myself dismissed the work as irrelevant, insisting (as per Palace propaganda) that the monarchy was not a major factor in the study of economics or modern politics, that it should be decentered in scholarly analyses in order to allow Isan and other people to “have their voices” and the like. Or they deliberately (mis)associated study of the monarchy with support of the same, ignoring the quite subversive content of my work.

Imagine my surprise when key words and concepts from my work popped up in leaked diplomatic cables from Wikileaks.

The American ambassador requested a copy of my dissertation, but dismissed the research findings as being of no real import.

A Buddhist activist dismissed Bangkok Bank’s connections with royal temples out of hand: “We know this already,” they said, joining the ranks of the hyper-blasé.

I was thus shocked many years later to find out that the dissertation had almost become a cult object. Among the first to really use it was journalist Paul Handley, who elaborated on the ritual mechanisms by which the King vastly expanded his wealth in a circle of ever multiplying merit (see Paul Handley’s The King never smiles, p 130). This was followed by a handful of scholars who addressed Thailand’s fiercely arbitrary lese-majeste law. Last came a younger generation of scholars (who studied under old masters) who ask, “Why haven’t I heard of this before?”

Ironically, even as the dissertation became a cult classic, often in pirated form (I can buy it online if I have the money), with a few notable exceptions (Pierre Bourdieu and a few imitators), the far-more-accessible articles sank like a stone.

I hesitated to go back into the water, and still do, for good reason.

Why do I care?

Khit theung.

Because I studied religion and ritual, I believe I saw much of the best of the country, or people at their best and most honest.

This included Palace officials, some of whom are now quite prominent; offspring of princes who knew history and the arts; frustrated female teachers and professors, highly trained and similarly trivialized; even Thanom and Praphat, whose reflections on past kathin rituals — Thanom took the north, Praphat the northeast, with both recoiling at the idea that they would offer kathin phraratchathan — were by definition reflections on their kamma, their fate, in the ugly aftermath of the demonstrations at Thammasat.

I spent many peaceful hours in the company of monks who were not charlatans or rascals, who took care of their communities. The same with socialist leaders from Isan.

I interviewed former ministers in the cabinet of Field Marshal Sarit, cosmopolitan bankers and economists who were quick to recognize the potential of linking kathin to their national development projects.

Since much of the work entails waiting, I passed many pleasurable hours in the company of Palace officials, photographers, astrologers and the like, each of whom had a role to play in the royal pageant.

I was shocked to encounter Kittivudho Bhikkhu, casually chatting with members of the Privy Council at a kathin rehearsal at Wat Mahathat run by ex-abbot Phra Phimonlatham: the talented, uppity Isan monk who lost his considerable seniority in the Sangha when Marshal Sarit, an ardent supporter of King Bhumibol, had him forcibly defrocked and jailed.

Kittivudho, friend of the royalist right, had trumpeted that “Killing communists was not demerit” because they were “like animals,” not real people. Many such kommunit were from Isan.

Devout Palace officials were genuinely perplexed that anyone would not love their king, although the Lord Chamberlain seemed a tad more cynical.

Most if not all were bursting with information that they could not divulge, a situation that would seem to persist in the present.

Exhausting. Demoralising.

In contrast, officials at the Department of Religious Affairs were often tired but never demoralized. Unlike their director — husband of a woman who owned a major bus company — most were actual religious specialists. For hours on end, they told lineage stories linking Isan meditation monks to their teachers and their teachers’ teachers, leading back to the time of King Mongkut, circling back to the present via royal kathin.

Thus it breaks my heart to see the junta tighten its grip under the guise of mourning the late king, piously declaring “No politics!” while the Crown Prince, on the merest of whims – or a series of seeming whims – sends his various audiences into a spin. The latter would include high-ranking members of the Royal Family, the military, the police, the government, the diplomatic corps, the international press, even, perhaps, his German real estate agents, to say nothing of Thailand’s so-called political parties.

Everyone has a good side and a bad side.

What we are seeing now is the bad side with perhaps worse to come as a lethal cocktail of intimidation and princely disruption builds on genuine (not manufactured) historical memory.

Thailand is a land of contradiction. We all want to be royalty, and we all want to escape it.

Everyone is afraid, for good reason.

Christine Gray, PhD, is a cultural anthropologist who writes about monarchy, ritual, gender and power.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss