Song lang (or song loan) is a wooden instrument to keep the tempo in cải lương—southern Vietnam’s traditional opera. In Sino-Vietnamese, the word means ‘two men’. Naming his debut feature ‘Song Lang’, Vietnam-born American director Leon Le has made an epic leap back to Saigon in the 1980s, when he left as a 13-year-old boy. The film is an emotional reunion with his childhood passion for southern traditional opera.

Song lang (or song loan) is a wooden instrument to keep the tempo in cải lương—southern Vietnam’s traditional opera. In Sino-Vietnamese, the word means ‘two men’. Naming his debut feature ‘Song Lang’, Vietnam-born American director Leon Le has made an epic leap back to Saigon in the 1980s, when he left as a 13-year-old boy. The film is an emotional reunion with his childhood passion for southern traditional opera.

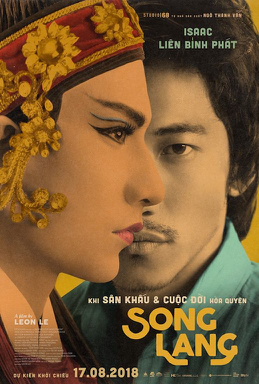

However, Song Lang is a film neither about cải lương nor Saigon. It is a film about the city’s people, their connections and how relationships shape their selves and life paths. At the focus of the film is a brief yet emotionally deep encounter between two men: Dũng, a debt collector (played by first-time actor Liên Bỉnh Phát) and Linh Phụng, a celebrated cải lương performer (played by Isaac, a Vietnamese popstar who undertook rigid training to perform several excerpts of cải lương in this movie).

With a limited budget, Le and his team do an excellent job of reviving the street-level everyday lives of Saigon’s dwellers in the 1980s, re-creating the past effervescence and popularity which cải lương used to enjoy. Excerpts from cải lương dramas, performed in adherence to the style of the 1980s, are a generous treat for contemporary audiences.

The time is the 1980s and the setting could be anywhere in Saigon where there are rundown apartment buildings, cải lương theatres, video game shops, noodle street stalls, cheap restaurants and slums. Living and working in such an area are cải lương performers, and their audiences, admirers and patrons. But equally, there are loan sharks, debt collectors, petty traders and poverty-stricken families who rely on urgent loans to meet their daily needs.

The filmmakers successfully revive this specific period in Saigon not through a large-scale simulation of the city’s crowded neighbourhoods, but by paying microscopic attention to objects that were used in the everyday lives of Saigonese at that time. People who lived in Saigon during those days will feel nostalgic in seeing again familiar things from their childhoods: Honda motorbikes of the 1960s-series, Nintendo game stations, cassette tapes.

Another achievement of Song Lang is its honest portrait of Saigon as a city in the middle of cultural, social and political transitions. This characterisation may not be easily comprehended by audiences not familiar with the city or with the post-war period in Vietnam. However, the film’s soundscape crisply portrays the crisscrossing,  multiple layers of cultural influences embedded in Saigon at that time. Mornings are filled with songs and speeches from public loudspeakers conveying citizen-making lessons targeting the new socialist city’s dwellers. This upbeat socialism is competed by southerners’ timeless love for melancholic songs, cải lương dramas, and Hong Kong movies—night-time back alleys are yet infused with pre-war sentimental songs and Vietnamese-dubbed dialogues from Hong Kong martial-art films. Sharp contrasts between light and shadow in almost every scene also vividly symbolise transition. Time-specific objects and sounds form a solid baseline for the story of love, art and personal transformation to unfold.

multiple layers of cultural influences embedded in Saigon at that time. Mornings are filled with songs and speeches from public loudspeakers conveying citizen-making lessons targeting the new socialist city’s dwellers. This upbeat socialism is competed by southerners’ timeless love for melancholic songs, cải lương dramas, and Hong Kong movies—night-time back alleys are yet infused with pre-war sentimental songs and Vietnamese-dubbed dialogues from Hong Kong martial-art films. Sharp contrasts between light and shadow in almost every scene also vividly symbolise transition. Time-specific objects and sounds form a solid baseline for the story of love, art and personal transformation to unfold.

Perhaps the greatest success of Song Lang lies in its subtle portrait of humans connections. Song Lang is a story about an encounter between soulmates. At the beginning of the film, Dũng and Phụng are from two separate social universes. Working for a cold-hearted and powerful loan shark, Dũng is notorious for his violent scare tactics to get debtors to pay up. Yet underneath his rough and aggressive appearance, Dũng is a kind and protective young man who lives a rather intellectual private life reading books, listening to music, playing đàn kìm (a Vietnamese traditional guitar which is part of cải lương orchestras) and growing pot plants. This middle-class lifestyle is the vivid remnant of his background as the only son of a pair of successful cải lương performers. Meanwhile, Phụng’s entire social life is confined within the theatre. A lone and introverted young man, Phụng only becomes full of life and complexities while on stage, embodying other characters.

Gradual developments in Dũng and Phụng’s relationship—from distance, to comradeship, and finally to an intense emotional bond—are convincingly acted. Dũng’s internal wounds and his healing process after meeting Phụng, and Phụng’s burning desire in his pursuit of love and art, are subtly expressed through the contrasts of crude dialogue, the looks in their eyes and body gestures. The scene in which the men stand next to each other by Dũng’s window, overlooking a neighbouring building in pure morning light, reveals the utmost joy and peace quietly shared by two soulmates who have finally found each other.

The film’s dramatic end is yet another brilliant touch by the director and his screenwriter Nguyễn Thị Minh Ngọc. It pushes its audience into unceasing thoughts about the fleetingness of humans connections, of life and about the random beauty in everyday encounters. Audiences may ponder how to name the relationship between Dũng and Phụng. Is it a homosexual love? Or is it a connection so special that it exceeds any gendered norms and makes the involved humans reach for their most beautiful selves? The film’s most haunting scene is when Phụng leaves his theatre with lonely and heavy steps, his eyes dim with immense sadness and disappointment. With this ending, director Le shows his determination to withhold an explicit definition for the relationship shared by the two men. Instead, the interpretation falls back to the audience, who may have to be content that Song Lang is a story about life. And life is where many mistakes are left unfixed, many puzzles are left unsolved, and many dreams left unpursued.

The film’s dramatic end is yet another brilliant touch by the director and his screenwriter Nguyễn Thị Minh Ngọc. It pushes its audience into unceasing thoughts about the fleetingness of humans connections, of life and about the random beauty in everyday encounters. Audiences may ponder how to name the relationship between Dũng and Phụng. Is it a homosexual love? Or is it a connection so special that it exceeds any gendered norms and makes the involved humans reach for their most beautiful selves? The film’s most haunting scene is when Phụng leaves his theatre with lonely and heavy steps, his eyes dim with immense sadness and disappointment. With this ending, director Le shows his determination to withhold an explicit definition for the relationship shared by the two men. Instead, the interpretation falls back to the audience, who may have to be content that Song Lang is a story about life. And life is where many mistakes are left unfixed, many puzzles are left unsolved, and many dreams left unpursued.

Song Lang (The Tap Box) was released by Studio 68 in Vietnam in August 2018. The film was directed by Leon Le. Screenplay by Leon Le and Nguyễn thị Minh Ngọc, cinematography by Bob Nguyen.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss