The outcome is known. The playing field is stacked. The political plays and players are largely the same.

Nevertheless, Singapore’s 2020 election is different—to paraphrase the words of PM Lee Hsien Loong’s label—it is ‘not normal’.

It is ‘not normal’ in the ways one thinks—the need to adopt special social distancing measures to address COVID-19; the banning of rallies, which undercuts the momentum of the campaign that has favoured the opposition; or in the use of fear and insecurities to win support. Changing the rules and capitalising on hyped negative sentiments tied to vulnerability have long been part of the play book of the longest ruling party in the world, the People’s Action Party (PAP).

Ironically, GE2020 is not a normal election because there is less fear. Sure, Singaporeans are deeply concerned about the pandemic—being among the countries most affected by COVID-19 in terms of confirmed case numbers (at 43,661 as of 29 June it ranks second after Indonesia in Southeast Asia). Singapore’s panic shopping videos are illustrative of underlying anxieties which have been compounded by the potential coming of the worst economic contraction the country has ever faced (estimated at -7.0 to -4.0 percent in GDP). Many Singaporeans remember the impact of SARS in 2003 and know COVID-19 is worse. Concerns about the pandemic and its economic impact are PAP’s ace in the hole—they expect voters to ‘fly to safety’, to maintain its base of support which usually reaches over 60% of the electorate and over 90% of the seats.

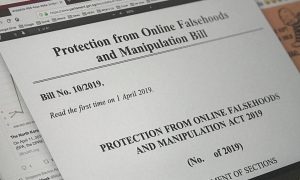

Yet, what is also clear is that more Singaporeans are speaking out on issues—and that Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA) is not shutting down discussion. In fact, the opposition and critics of the PAP have prepared for an online campaign and are raising issues, challenging PAP government narratives and offering their own. The biggest outcry is coming from the general public as a social media dominant campaign is empowering ‘ordinary’ voices outside of rubric of political parties.

This dissipation of fear reflects the growing confidence Singaporeans feel about themselves. Singaporeans are more politically sophisticated and the society has become more pluralistic in views. Support for PINKDOT and mobilization over climate change are increasingly the norm, not the exception. There is less hesitancy to openly discuss race and religion, two traditionally taboo areas. As such, there is more familiarity and engagement with alternatives views, and while many alternatives parties or candidates are not necessarily as well-supported as is PAP, they are heard and accepted as part of the landscape. Difference and choice have become normal in Singaporean elections since 2011, and this has expanded further to a degree that this in and of itself is ‘not normal’.

With 10 opposition parties, and at least three of them oiled and social media savvy—the stalwart Worker’s Party, the agenda-setting Singapore Democratic Party and new-old-kid off the block Tan Cheng Bock’s Progressive Singapore Party (supported by none other than PM Lee Hsien Loong’s brother Lee Hsien Yang)—the opposition plays a major role in shaping the election narratives.

Bucking the tameness of earlier campaigns, many of the issues that are being raised are more hard-hitting this time round—and are being driven by the public as much as by political parties. The outcry over the selection of PAP elitist candidate, Ivan Lim, who has been portrayed as selfish and lacking empathy, and later withdrew, was almost instantaneous on social media. Old issues such as salaries have moved from Cabinet to the wife of a Cabinet member. Issues such as the performance of the Central Provident Fund deflect attention from how money is spent to how money is managed—going to the core of the PAP’s economic legitimacy. The attention on the conditions of foreign workers in Singapore—not seen as part of the ‘community’—has starkly brought home inequalities and quietly raised persistent questions about how reliance on foreign labour and talent is shaping Singapore’s economy. Traditional lets-not-be Malaysia campaign mobilisation has transformed from a nationalist rally call to one that draws attention to differences within Singapore. Many of these issues are captured in cutting messages and colorful memes. Here too, the social embeddedness and scope of discussion of these issues is ‘not normal’

What stands out, however, as the most unique ‘not normal’ feature of these polls is greater uncertainty about Singapore’s future. While 2015 was about Singapore’s past, 2020 is about the vision for its future —as Lee Hsien Loong aptly described when laying out the PAP’s manifesto. This future, however, is much murkier than before. Singaporeans have long thought that, even as the vulnerable ‘little Red Dot’, they would be okay. PAP was there to protect and guide them.

PAP leaders have yet to reposition Singapore effectively in the new international and regional conditions, in today’s era of deglobalisation and heightened Great Power rivalries. Singapore’s growth model still rests on riding globalisation, bringing in foreign talent and labour and the government-knows-best mindset.

Singapore’s GE2020 is being couched as an endorsement for the 4G (Fourth Generation) leaders and the chosen successor Heng Swee Keat, currently Minister of Finance and the nation’s most generous one in terms of spending (with $72 billion or 20% of GDP doled out in the last few months). Yet, so far, these leaders have yet to engage in meaningful reform and outline a different vision. This lack of assurance is ‘not normal.’

PAP realism in an endangered world

PAP realism means accepting the conservative position of moderating one’s political aspirations and campaigns to align with values shaped by Singapore's ruling party.

These circumstances have not been in place since Lee Kuan Yew and the first generation of PAP leaders led Singapore. While PAP is slating nearly a third new and younger candidates in its slate of contenders, today’s 4G leaders have neither the same legitimacy of the country’s founding leaders nor the same space to address today’s challenges—in part due to the fact that it is today’s PAP that has not adapted Singapore for current uncertainties.

Singapore GE2020 showcases that the PAP has less control than they had in the past and they cannot rely primarily on control at home. This longest-serving incumbent party will easily win the election, but will likely be bruised in the campaign. Irrespective of the outcome, PAP will have a hard time trying to make things ‘normal’ after the elections. The ‘not normal’ mode is going to be around for some time.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss