The People’s Action Party’s election victory is the optimal pendulum swing, argues Bridget Welsh.

Singapore’s ruling party led by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong secured a decisive victory in the country’s 12th General Elections overnight.

By all accounts – including my own – they won 69.9 per cent of the popular vote, cutting into the 2011 election gains of the Worker’s Party who lost one of its seats, as well as soundly defeating the opposition as a whole.

The result came as a surprise.

My best scenario for the PAP was reaching 65 per cent of the popular vote and potentially picking up Punggol East. They exceeded this, almost winning back the Aljunied Group Representation Constituency (GRC) in a close margin.

The electoral outcome raises important questions ranging from why the election mood was misread to what the implications will be for the policy landscape. Here are some initial observations.

Silent majority speaks

The results show that a majority of Singaporeans want the PAP to be in government. Many of those are the ‘silent majority’. While not vocal or active in political life, they expressed themselves at the polling booths yesterday.

Singapore’s silent majority is especially large due to the compulsory voting required of all its citizens. It is large also because the political climate does not have a clear sense of their views. Despite considerable opening up in political discourse, a tradition of not speaking out about politics still permeates parts of Singaporeans society, especially among older generations.

Political polling remains limited. Yesterday this group made itself heard.

Opposition blowback

Campaigns in Singapore do shape the electorate, and this one was no exception.

As polling day approached, the opposition’s messages and prominence in the media gained traction. The prominent messages and large crowds provoked a counter-reaction that boosted the PAP performance, an opposition blowback.

For some this was about unease with the opposition itself, be it disappointment in performance or distrust. For others it was about balancing, as the PAP was seen to be less favoured and facing a tough challenge. The stronger the opposition became, the stronger the response against the opposition, especially among the silent majority.

Opposition blowback contributed to a greater pendulum swing in PAP’s favor, as the incumbent party took on the mantle of the disadvantaged. The PAP fanned this effectively by stoking fears that it might be replaced in government.

Right timing

Timing played a large part in enhancing the PAP victory. The obvious markers involve the impact of the passing of Lee Kuan Yew and Singapore’s 50th anniversary of nationhood this year, which evoked sentiment and appealed to the heartstrings of many Singaporeans.

In supporting the incumbent, this was an acknowledgement of the governance of the Lee family, as the father helped the son (in part) to secure a strong mandate.

There were other facets as well, notably economic conditions.

Singaporeans are acutely aware of the dark clouds over the region’s economy and have experienced the slowdown themselves. In times of economic insecurity, as occurred in the 2001 election, Singaporean voters go where they are most secure and to whom they have the most trust in managing the uncertainties. This advantaged the PAP.

Anger dissipation

The interventions of the PAP in areas such as subsidies and health care made a difference among voters. This was credited at the polls, but the move in the electorate was a broader dynamic. The anger of voters had dissipated.

Even in opposition rallies, the pull of supporters was as much about the positive messaging of empowerment and a more open society that appealed to that segment of the electorate as it was about the negative anti-PAP messaging.

While anger still exists and nearly one-third of the electorate supports alternatives, the level of acrimony in the middle ground particularly reduced. It is not a coincidence that the opposition parties that adopted the most confrontational and angry stances in their campaigns performed comparatively the poorest.

His own mandate

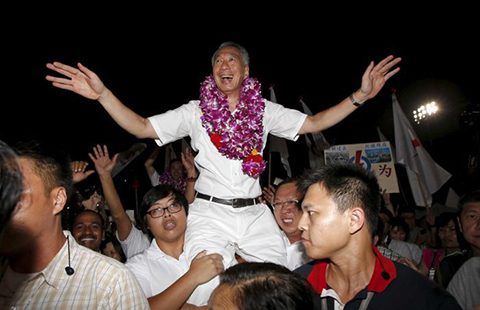

The biggest winner in this campaign is Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong.

He has secured his own mandate and will have the space to carve his own legacy without his father’s shadow and to set the path ahead for the leadership transition in his party. He deserves to be congratulated on his victory.

The PAP leaders are now HIS team. Deputy Prime Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam – whose policy interventions in expanding social welfare contributed to Lee’s victory– will be particularly prominent.

The main attention however will focus on the younger entrants who now will define the fourth generation of PAP leadership. There will be intense competition among this group for position, and Lee will be able to use this to his own advantage to strengthen his governance and shape his own legacy.

Raising standards

For both sides of the political divide, the election has strengthened their engagement with a more demanding electorate and offers the promise of raising standards further.

While performing below expectations, the opposition has given voters clear choices. Worker’s Party and to a lesser extent the Singapore Democratic Party have resonated among a larger share of the electorate compared to other opposition parties. But their appeals failed to dent the PAP base and lost support in the middle ground, notably the silent majority.

The burden is now on the opposition to move beyond ‘walking the ground’ in specific constituencies and capitalising on anger, to developing a broader appeal that reaches those not politically active. Improving performance in parliament and focusing less on personality will be essential ingredients in this process.

For the PAP, one of the biggest challenges will be complacency.

The effort that was invested in securing the outcome and the timing of the 2015 polls will not be replicable. The large margins in many seats – even mistakenly perceived close seats – and the almost 10 per cent swing toward the incumbent party should not be seen as an ‘easy win’.

Singaporeans expected to be heard and felt at least in part they were reasonably so. The PAP’s optimal victory in swinging the pendulum in its favour was hard work in an intense contest. It will also require hard work ahead.

If anything the 2015 election shows is that the pendulum can indeed swing back.

Bridget Welsh is a Senior Research Associate of the Center for East Asia Democratic Studies of the National Taiwan University where she conducts research on democracy and politics in Southeast Asia. She is also an Associate Fellow at The Habibie Center and University Fellow at Charles Darwin University.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss