It is not easy to place Singapore in Southeast Asian studies. It is richer and more organized than its neighbors. It is a city-state with no physical hinterland (‘tiny red dot’ as former Indonesian president Habibie put it). It has achieved economic success under an authoritarian government. To many Southeast Asianists, Singapore is both exceptional and uninteresting.

However, Singapore has many similarities and some differences with other Southeast Asian cities. As in Singapore, large swathes of metropolitan Manila, Bangkok, Jakarta, and Kuala Lumpur today are dominated by mega projects (infrastructure, malls and private housing). As Gavin Shatkin (2006) notes of Manila, the organizing force in the city is no longer the state but global capital.

There is a mega project of another sort, undertaken by the state, where Singapore also resonates with other Southeast Asian cities. Under both authoritarian and post-authoritarian regimes (Indonesia and the Philippines under and after Suharto and Marcos respectively), and in countries emerging from conflict (Cambodia), the state has forcibly removed informal settlers, often without regard for their rehousing and livelihood (UN Habitat 2007, Human Rights Watch 2006, Cambodian League for the Defense of Land and Human Rights 2009).

Singapore’s landuse struggles are long over – four-fifths of the population now reside in state-built housing, the purchase and upgrading of which are sought after. But Singapore also has a history of informal settlements in the decades immediately after World War Two, culminating in a struggle that decided the face of the city-state. In my new book, Squatters into Citizens: The 1961 Bukit Ho Swee Fire and the Making of Modern Singapore, I traced how the vision of a planned city – an ideal imagined by Anglo-American planners – was achieved in the aftermath of a great fire in an informal settlement called Bukit Ho Swee in 1961.

Caption: Informal housing in Covent Garden, Singapore, 1950s. Courtesy of Robert Yong.

In the 1950s and 1960s, rapid population growth, extensive rural migration and the lack of affordable alternative housing led many low-income families to reside in unauthorized houses built in marginal spaces in Southeast Asia’s cities, on hills, alongside rivers and railway lines and over cemeteries and swamps. In 1961, informal settlers comprised between a fifth and a quarter of the populations of Singapore, Manila, Kuala Lumpur, and Jakarta.

Western planners warned of the dangers of such disorderly urban growth. In their view, informal settlers were a threat not only to their own well-being but to the city and country as a whole. One of them, Morris Juppenlatz, an Australian architect, had worked in Australia, Cyprus, the Philippines, and Brazil. For planners like him, the insanitary informal settlement was literally a fungus – a disease – afflicting the city, and spreading quickly (Juppenlatz 1970).

The experts proposed a single remedy: the city to be zoned according to landuse and informal settlers to be moved to clean housing in planned estates and new towns. The proper agency to undertake such a task, the experts recommended, was the state. Such an idea attested to a high modernist desire to impose a visual form of order from above and to render the city’s denizens legible (Scott 1998). A United Nations mission visited cities in South and Southeast Asia in 1951; it was headed by American planner Jacob Crane, who possessed extensive experience in the United States and other countries. Emphasizing the need for national-level action, the mission warned of a great zone of urban crisis: ‘[p]revailing conditions in Asia create the greatest housing problems in the world’ (United Nations Tropical Housing Mission 1951).

In fact, experts, states and informal settlers were locked in an irreconcilable conflict arising from two global events of the time: decolonization and the Cold War. The experts urged that organized cities were vital to the country’s development. Juppenlatz (1970) argued that moving informal settlers into planned housing would transform them into responsible tax-paying citizens. For American planners, eradicating informal settlements was essential to containing the spread of communism in the Third World. American planner Charles Abrams was a member of various United Nations missions to Pakistan, India, the Philippines, and Singapore. Abrams (1966) saw informal settlements as ‘the haven of the refugee, the hungry, the politically oppressed’, and their removal would help maintain ‘the rule of law and the basic sovereignty of the state’ in strong democracies.

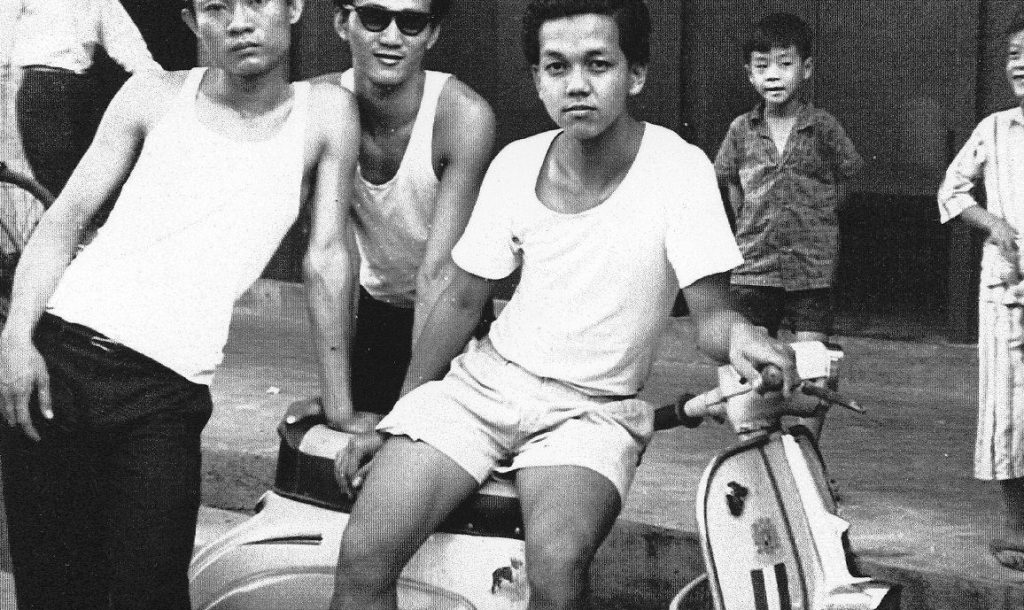

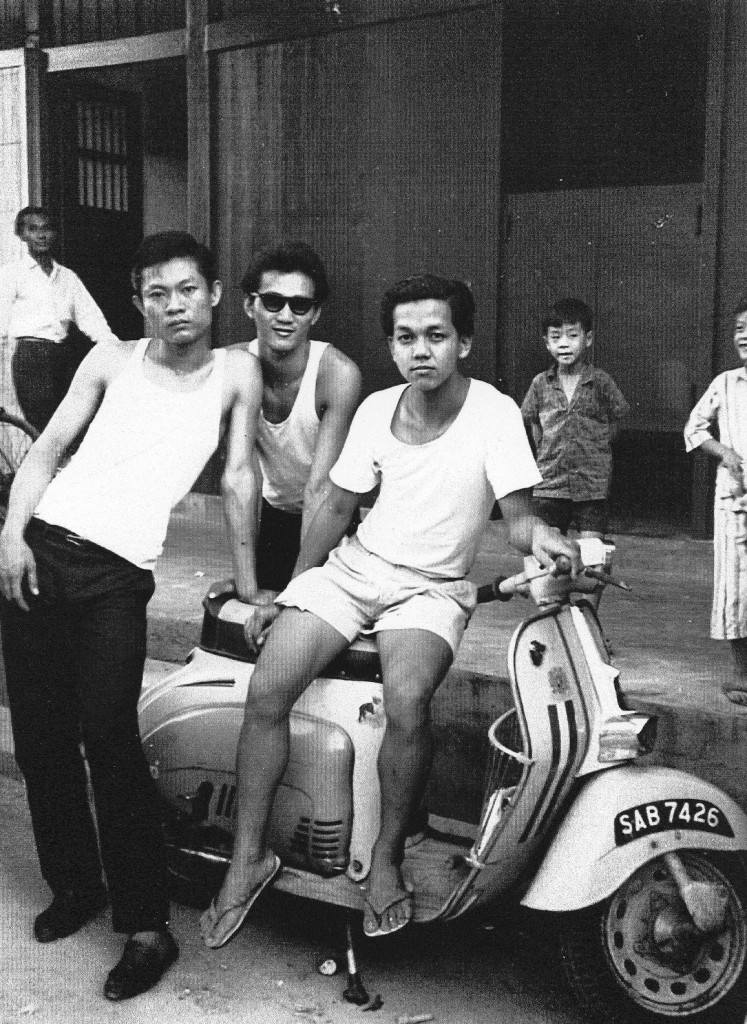

Caption: The informal settlers. Note their posture, shades and motorcycle to indicate their relationship with modernity. Courtesy of Wong Pok Hee.

In postwar Singapore, as elsewhere, informal settlers mobilized against colonial rule. In organizing the collective defense of their housing rights, farmers’ and rural associations became an important part of the broad-based leftwing movement headed by the People’s Action Party (PAP), then an oppositional party. The informal settlers also formed fire-fighting squads, made up of underemployed youths, against the threat of fire. These squads received training from both the city council and left-wing groups. Herein was the historical irony: the more the informal settlers participated in national politics, the more they were circumscribed within the expanding structures of the state.

The technical advice on planned cities, while claiming to be universal, was conditioned by European and American historical experiences of their own cities. The expertise grew out of modernization theory and the discourse of urban overpopulation in the developing world prevailing in Western professional and academic circles after the war. Alternately ignored and translated into practice by Southeast Asians, the expertise made little of the impact the planners envisaged. Most planned housing projects and agencies remained ‘paper plans’. Actual efforts to rehouse informal settlers to planned areas – to Petaling Jaya in Malaysia in 1951 and Sapang Palay in the Philippines in 1963 – were dismal failures. Presidents, mayors and petty officials also made use of the planning wisdom to cultivate political constituents. Between 1950 and 1972, the Thai government decided to launch eight expensive public housing projects in Bangkok because this was more politically visible than improving the slums.

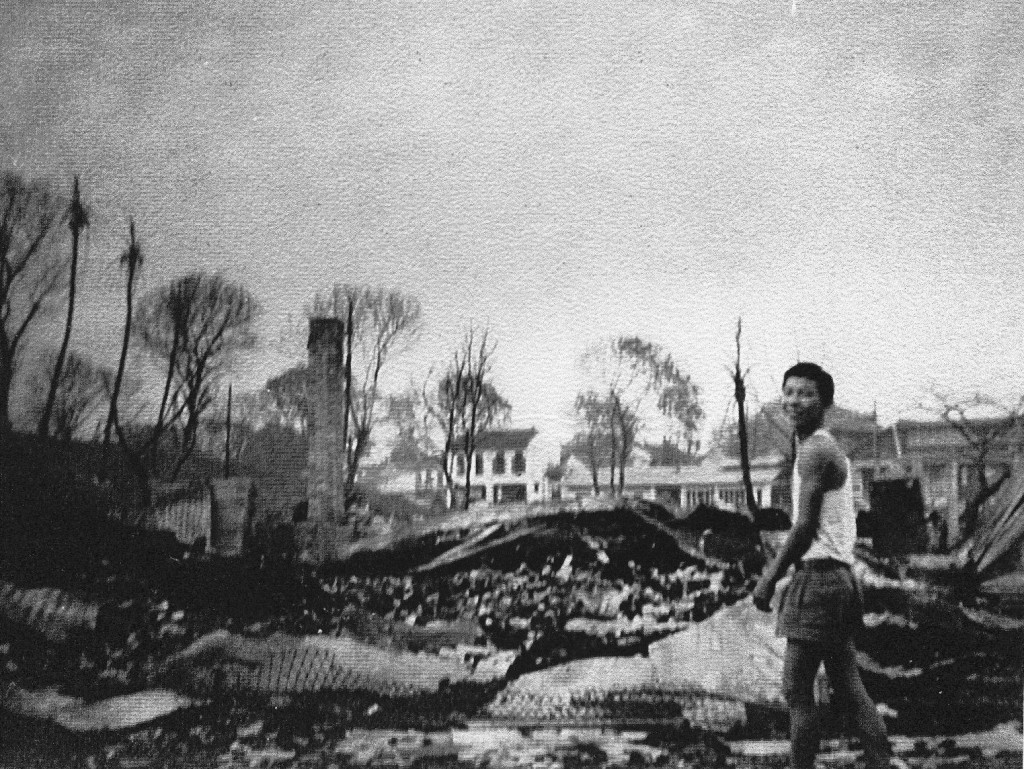

There was, however, a different outcome in Singapore, where transnational and national forces converged. When the PAP was elected to power in 1959, one of its first moves was to build large numbers of multi-storey emergency flats. On 25 May 1961, a fire broke out in Bukit Ho Swee – the greatest in Singapore’s history – rendering almost 16,000 people homeless. Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew assured them that each family would have a rental flat within nine months – a promise rich in the political symbolism of the birth of a new nation. The fire site was quickly acquired for emergency housing and over the next five years, 75,000 flats with one, two and three rooms (including the living room) were built over it. But Bukit Ho Swee was not just a heroic story of rehousing destitute fire victims. It became the spearhead for clearing informal settlements nearby, and subsequently the inner-city slums. By 1970, the squatters were on their way into history and the government declared that Singapore’s public housing achievements duly met ‘the needs of a modern metropolis and a new nation’ (Radio Corporation of Singapore 1972).

Caption: Bukit Ho Swee after the fire. Courtesy of Wong Pok Hee.

Singapore was a classic case of orderly decolonization pursued by the British: a vital part of the rehousing involved the suppression of the leftwing rural associations in the early 1960s. Former squatters who became tenants (later owners) of public housing were transformed into model citizen-workers. Paying rentals to the state, they had obtain regular work in the formal economy – in state-linked agencies and in foreign industrial firms which were relocating to Singapore from the early 1970s.

However, Singapore was not a shining example of liberal democracy as the experts had hoped for. Lee Kuan Yew’s government took a hard-nosed approach to its development, tolerating no resistance. For architects and planners working for the state, that ‘you cannot make an omelet without breaking eggs’ was an imperative; they did not realize that the phrase had been used by French revolutionaries and Russian communists. Public housing became not merely a plank of development and social engineering but a source of political legitimacy for the PAP. In this sense, the political nature of housing in Singapore is not unusual in the region, where Western planning expertise became means of entrenching authoritarian rule and patronage politics.

There is perhaps a wider lesson about the effects of international expertise. The social value of public housing in Singapore is quite exceptional but what is not is the belief in the mega projects being implemented across cities in the region. These projects articulate a fierce vision of a superior future and are informed variously by state imperatives of nation-building, movements of global capital and ideas of development drawn from other cultures. They represent attempts to master the city from above and outside. Shahtkin (2006) sees global capital as diminishing public space for social and political activism in Manila. In Singapore, public housing has bred a culture of dependency, as informal settlers who hitherto decided where they would live now did so according to terms prescribed by the state. The PAP’s attempt to forge ‘Thinking Schools, Learning Nation’ in the late 1990s reveals the social price of citizenship. The government has had to address the social consequences of having gone too far and too fast in its single-minded pursuit of economic success.

For states, experts and urban residents alike in a region historically open to external trade and ideas, mega projects and ambitious social programming may have unpredictable consequences.

Loh Kah Seng is assistant professor at the Institute for East Asian Studies at Sogang University. Squatters into Citizens: The 1961 Bukit Ho Swee Fire and the Making of Modern Singapore is published by NUS Press and Asian Studies of Australia Association Southeast Asia Series. Details on the book are available here.

The author in Bukit Ho Swee Estate where he grew up. Courtesy of Loh Tian Ho.

References

Abrams, Charles. 1966. Housing in the Modern World. London: Faber.

Cambodian League for the Defense of Land and Human Rights (LICADHO). 2009. Land Grabbing and Poverty in Cambodia: The Myth of Development. LICADHO.

Human Rights Watch. 2006. Condemned Communities: Forced Evictions in Jakarta. Vol. 18, No. 10 (C), September.

Juppenlatz, Morris. 1970. Cities in Transformation: The Urban Squatter Problem of the Developing World. St. Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

Radio Corporation of Singapore. 1972. Then and Now (No. 1): ‘A Look At Housing. 16 September.

Scott, James C. 1998. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Shatkin, Gavin. 2006. ‘Colonial Capital, Modernist Capital, Global Capital: The Changing Political Symbolism of Urban Space in Metro Manila, the Philippines’. Pacific Affairs, 78 (4): 577-600.

UN Habitat. 2007. Forced Evictions – Towards Solutions? UN Habitat.

United Nations Tropical Housing Mission. 1951. Low Cost Housing in South and South-east Asia: Report of Mission of Experts, 22 November 1950 – 23 January 1951. United Nations Secretariat. Department of Social Affairs.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss