Trekking to London for Thongchai Winichakul’s talk on 28 November 2006, I wasn’t quite sure what to expect. The last time I attended a Thai Studies event in London – the talk given by Kraisak Choonhavan and Sondhi Limthongkul.back in mid-October – it was jam packed and, at times, just a little bit tense. In contrast, Thongchai’s talk was a more relaxed affair. His interpretation of recent political events didn’t seem to provoke any of the candid opposition that confronted Kraisak and Sondhi. Thongchai was, somewhat to my surprise, greeted by a generally receptive audience – patient to clarify his thoughts on the trajectory of Thai politics and, in particular, the role of the King and royally-aligned elites.

Regular New Mandala readers will recall that the October SOAS event was publicly condemned by Singapore based Thai Studies specialist Dr Patrick Jory. Jory, and other critics of SOAS’ initial post-coup offering, may be partly sated by SOAS’ collaboration in this most recent Thai Studies event. As my account of Thongchai’s lecture should make clear, a largely well-received case was made against 19 September style Royally-sponsored, anti-democratic interventions.

As usual, a free and frank debate of Thongchai’s ideas, and other perspectives on the coup, is very welcome here on New Mandala. All shades of opinion can be aired.

This open invitation comes with the warning that, by virtue of the medium, I am forced, in this post, to extensively paraphrase and quote Thongchai’s arguments. Some of the finer points of his lecture may have been lost in my interpretation but, in general, I feel that this is a clear, if relatively dull, account of proceedings. I have also included a number of images to show the tone and style of Thongchai’s 26 power-point slides. I hope that my account makes a small contribution to the essential debates that are currently stewing. All we can really hope is that from this process of argument and analysis will come improved understanding of Thai political organisation. And perhaps a few ideas about making politics – whether in Thailand, Australia, Burma or the United States – work better for all.

The Talk, 28 November 2006 – “Thailand’s September Coup: One Step Backward to Restart Democracy or One Step Forward in a Wrong Direction?”

Thongchai Winichakul was introduced to the audience – composed, to my eye, mainly of London-based students and academics (there was a small Oxford contingent) – by SOAS Thai lecturer Dr Rachel Harrison. Regular New Mandala readers will remember that Dr Harrison also introduced Kraisak and Sondhi at the controversial October event. In her brief overview of Thongchai’s life and work, Harrison mentioned that he spent almost two years in a Thai prison in the 1970s as punishment for his opposition to military rule. She also noted that his subsequent doctoral research at the University of Sydney was supervised by eminent historian, Dr Craig Reynolds, who is now based at the ANU. Harrison briefly discussed Thongchai’s famous contribution to Thai historiography, Siam Mapped: A History of the Geo-Body of a Nation, and the generally high esteem in which serious scholars hold his historical work. Thongchai is, according to Harrison, currently working on a new book that examines “moments of silence” in Thai history and historiography. By the sounds of it, it will be worth looking for when it hits the shelves.

After this very positive introduction, Thongchai paused before launching into his argument and his lecture. He began on a personal note. He reflected that under current circumstances, with so much uncertainty, and some people trying to pick sides, many “academics become politicians”. In an attempt to buck this trend, Thongchai indicated that after his current batch of talks he plans to return to “academic” work. He described this work, by way of clarification, as being critical and historical in focus.

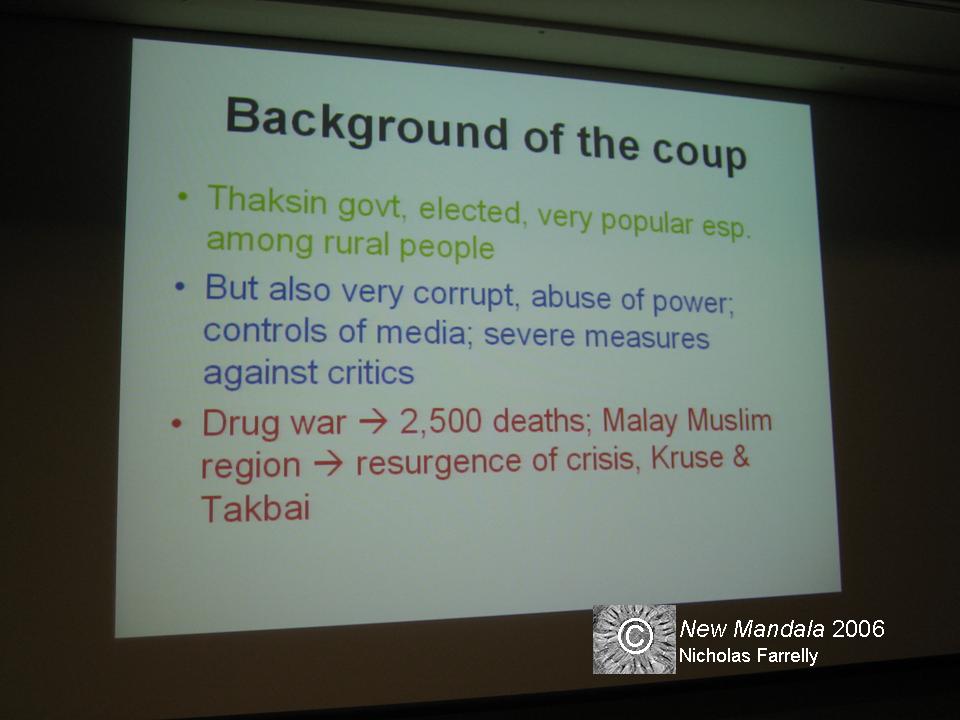

Thongchai began the lecture, firstly, with an introduction to the political scene in Thailand. To my eye, the audience generally appeared to have a good grasp of the nuts and bolts of this overview. Many heads nodded throughout. In particular, Thongchai highlighted the “sins” of the Thaksin government and clarified the reasons for much popular discontent with Thaksin’s rule. This discussion clearly showed how polarisation had occurred. The stark oppositional positions that have resulted are, of course, something that is not unfamiliar to regular readers of New Mandala. Thongchai simply put the various arguments in their national context. Thongchai then indicated that he was more interested, unsurprisingly given his chosen vocation, in seeing the recent coup in longer historical perspective.

Apparently, this approach has drawn the ire of some of his academic colleagues. Thongchai related that he has been criticised by colleagues in Thailand for two main reasons. Thongchai is, they posit, outside the country, and thus has a more limited understanding of contemporary problems. He is also, they say, pro-Thaksin and blinded by his devotion to the man. He dismissed these criticisms and thought it laughable that he could be described as pro-Thaksin. He argued, quite forthrightly, that he has no intention to defend Thaksin but, as a point of clarification, noted that his current arguments emerge from a simple point: “I just don’t like the coup”.

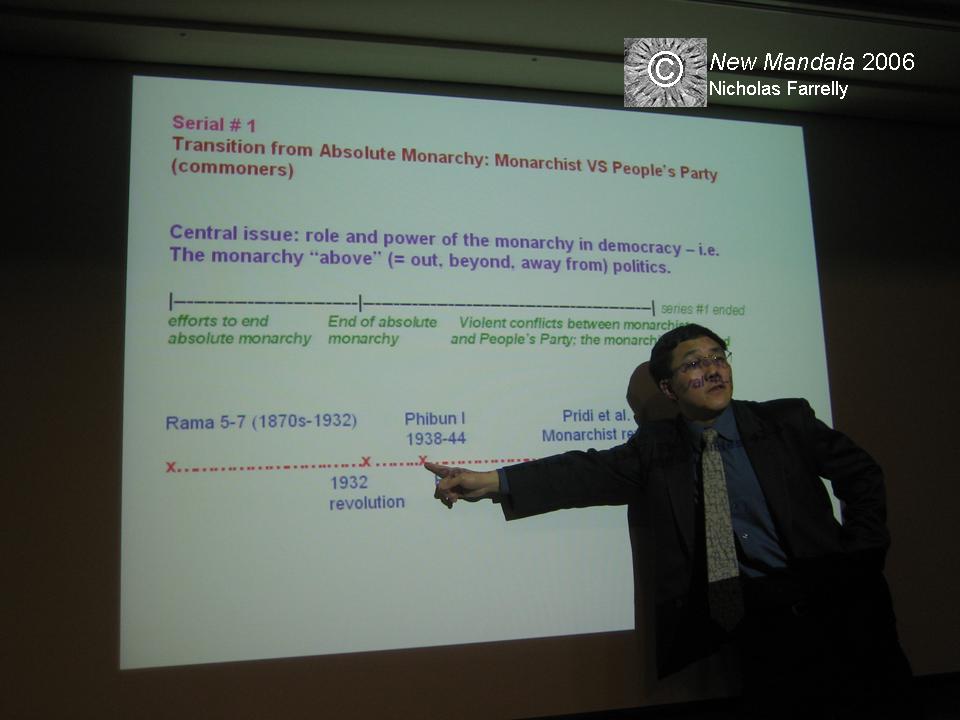

Thongchai’s talk repeated his key theme of injecting some historical rigour into discussion of September’s events. The emphasis, in his mind, should not be merely on “yesterday and tomorrow” but rather on the longer-term development of Thai political actors and their political system. He positioned his argument as an “atypical view” which sees Thai history as a “series of three main conflicts”.

In this talk, Thongchai, firstly, highlighted Series 2: “military versus civilian conflict”. This is, he argued, the most familiar conflict for the current generation of Thais. In fact, Thongchai asserted that most people only see this conflict and largely ignore the other series that overlap with the commonly described tension between military and civilian control. As part of this series, which stretched for most of the 20th century, Thongchai highlighted the existence of parliaments that operated within a system of military power. There was, under these conditions, a number of periods where something approaching “semi-democracy” was allowed to flourish. To illustrate this point using the career of Thailand’s most recognisable senior Statesman as a benchmark, Thongchai noted that “Prem never went through elections”. General Prem is now, of course, the Chairman of the Privy Council. He has been a key player in Thai politics for many decades and his longevity as a political force is remarkable. But he has not fought and won elections. Thongchai returned to Prem in the conclusion of his talk. Read on – to see where Thongchai places Prem in the broader picture he tries to paint. The era of conflict between military and civilian control ends, abruptly in Thongchai’s view, with the violent events of 1992.

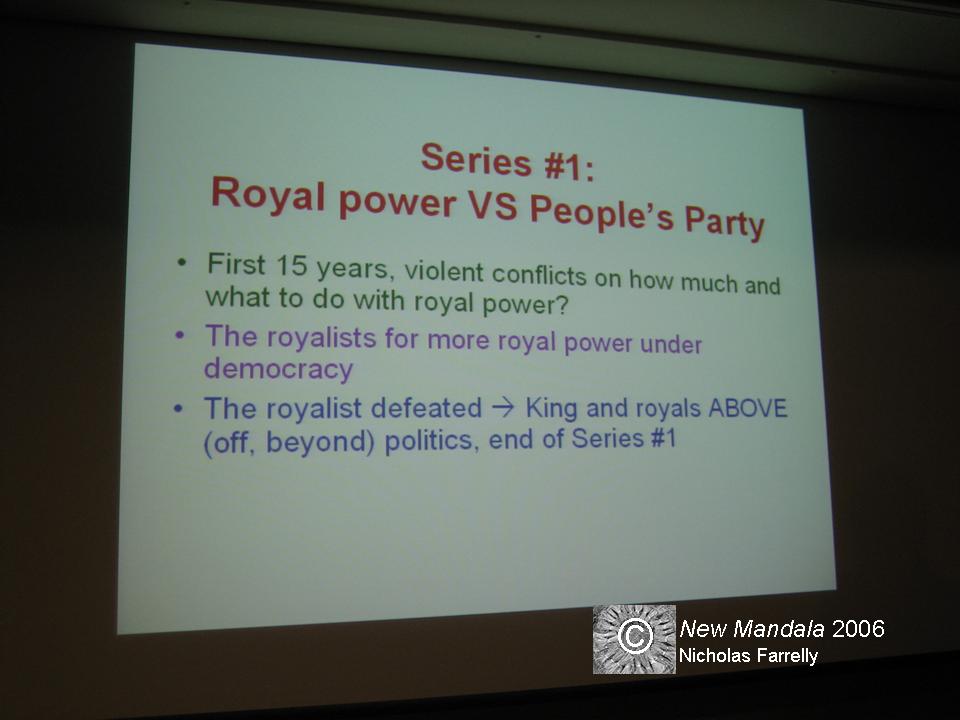

Series 1 is a less conventional interpretation of modern Thai history. This interpretation is, at least from my viewpoint, one that seems to be gaining currency and acceptance in many current debates. Series 1 highlights the conflicts that have pitted “Royal power against people’s power”. According to Thongchai, between 1932 and 1945 – in the immediate aftermath of the “Royal gift” of constitutional monarchy – there was a great deal of conflict that can be best explained with reference to this particular series. In October 1933, for example, there was conflict spurred by those seeking the “restoration of Royal power”. The elite stoushes of this period continued for years. For those interested in how a “Royalist democracy” could be instigated, Thongchai suggested that the 1949 constitution was a good place to begin interpreting Royalist visions of government and power. Discussing this series, and its implications in the current day, Thongchai said that “history is so cruel, fantastic…it never allows anybody to have what they want”.

In Thongchai’s historical overview, Series 3 describes the power relations among what he rather playfully called “M/P3”. This is the series that focuses on the interactions between “Politicians (elected)/Money; People/Mass; Palace/Monarchists, Monarchy”. He sees this series, which begins in 1973, as heralding “the revival of the monarchy”. Speaking of the bloody events of October 1976, Thongchai argued that nobody mentions that “the King’s intervention is part of the massacre”. This is all part of Series 3. In this scheme, “Royalists now talk democracy” and have, very cunningly, created an “upper floor of politics”. This is a “second floor [that] provides the moral authority”. On this point, and as a digression, Thongchai briefly noted that Paul Handley’s widely debated book, The King Never Smiles, is, in his view, “not academic but worth listening to”.

Having galloped across a turbulent century of Thai political evolution, and introduced his three descriptive summary series to describe different types of conflict and tension, Thongchai started warming up for his punchline. In Thailand, according to Thongchai, discourses around “clean politics” and extra-electoral interventions are a real test of commitment to democracy and democratic institutions. In a poignant, rhetorical flourish, Thongchai asked the audience whether even though President Bush “is even worse [than Thaksin], does he deserve a coup?”

To begin answering this question, and what it means for Thai politics, Thongchai mentioned some anthropologists that he has communicated with who completed detailed studies of village-level politics during the Thaksin era. These anthropologists told Thongchai that “people elected Thaksin because of what he promised and he delivered…What they wanted is different than people in Bangkok”. This manifestation of electoral will has been widely discussed here on New Mandala. There are usually two standard positions. Thongchai strongly supports the view that democracies need to be defended even when they produce what some people consider to be “immoral” results.

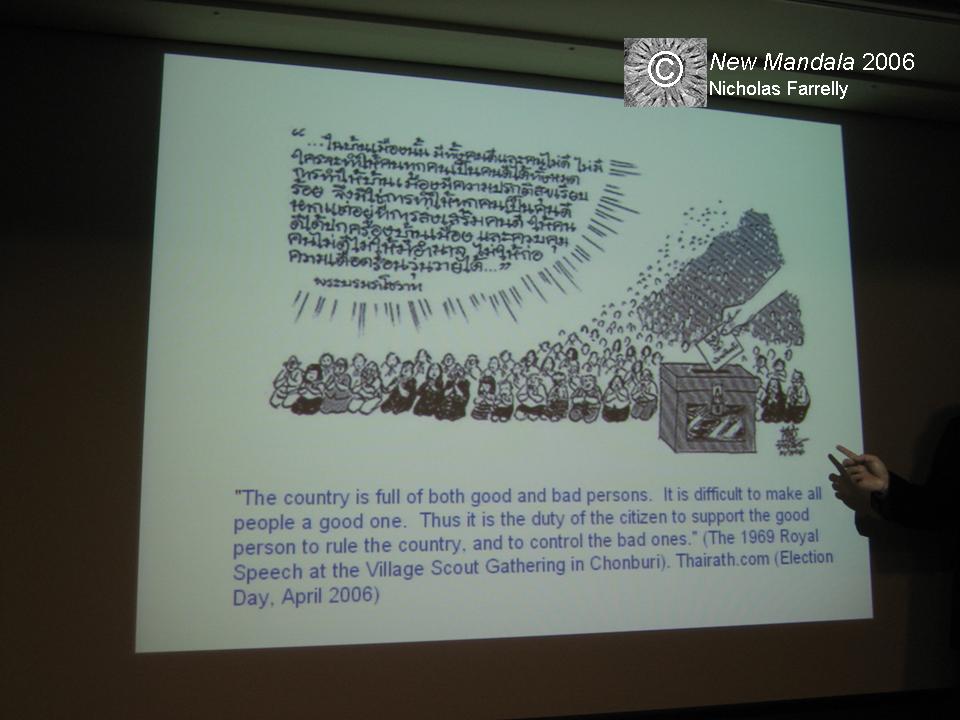

And this brings Thongchai to his discussion of the “Royalist coup” including the reasons that it happened and the longer term ramifications of 19 September. Thongchai said that this Royal coup fits nicely within elite perceptions of “a moral coup” that reinforces the notion that democracy equals moral rule. This position is based in “calls for the moral authority above politics”. Here, Thongchai was particularly scathing of one example he raised: Thirayut Bunmee’s suggestion that a “Council of Moral Authority” including military leaders, judges, privy councillors and academics should be instituted to provide guidance and governance.

But this is all just preamble to Thongchai’s final volley. In Thongchai’s view the coup was, on some level, motivated by concerns about succession. Paul Handley has also recently discussed this important issue. In this part of his talk, Thongchai focussed on “the King-makers in Thai history” and argued that “the nobles are the real power”. What occurred in September was one episode in a battle between two factions of ambitious Kingmakers – Thaksin and cronies vs Prem and friends. Prem is, Thongchai concluded, “the mastermind of this coup”.

To wrap up his argument, Thongchai related that “rumours about royalty are often true”. In his view, the tight control of most palace information ensures that “rumours are a source” and in this case he exalted the audience to “help spread the rumour”. His forceful argument, and one that he is happy to make without resorting to pseudonyms or crude personal attacks, makes a very refreshing change. In his view, “Royalists worried that Thaksin was privatising monarchy” and forced the Prem faction of Kingmakers to retake control.

And so the rumour spreads.

As always, New Mandala reader contributions to the debate about these important and controversial ideas are very much encouraged.

More about Thongchai’s views on the coup is available from a number of good sources including: Prachatai, Blog Gang, Thailand Coup Watch, and right here at New Mandala.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss