A principle of social movements seems to be that once a movement is written about there’s a good chance it is now over or changed in some fundamental way. With this in mind, it’s not clear what to make of Pemuda Hijrah, a Bandung-based youth movement whose name references the Prophet Muhammad’s emigration or flight from Mecca to Madina in 622—Year Zero in the Islamic calendar.

Over the past 18 months I’ve watched as Pemuda Hijrah has gone from a local religious revival movement in Bandung to a viral phenomenon attracting national news coverage. For months now on Instagram the most popular Muslim preacher in the largest Muslim-majority country in the world is Pemuda Hijrah founder Hanan Attaki, who has 3.5 million followers. Fast gaining on him is his protégé, Muzammil Hasballah, with 2.3 million followers (the same number as the old-school celebrity preacher Aa Gym.) The group has developed this following largely under the radar of the mainstream media, in the belief that there’s a trade-off between mainstream popularity and counter-cultural chic.

PHOTO: @PEMUDAHIJRAH ON INSTAGRAM

The secret to their success? It’s much more than clever social media marketing—although at that they have few rivals. Some call their approach “Street Outreach” (Dakwah Jalanan). Very deliberately, Pemuda Hijrah has gone out and recruited from urban communities of musicians, bikers, skaters, street soccer players, and parkour groups—youth who are alienated from traditional religious institutions.

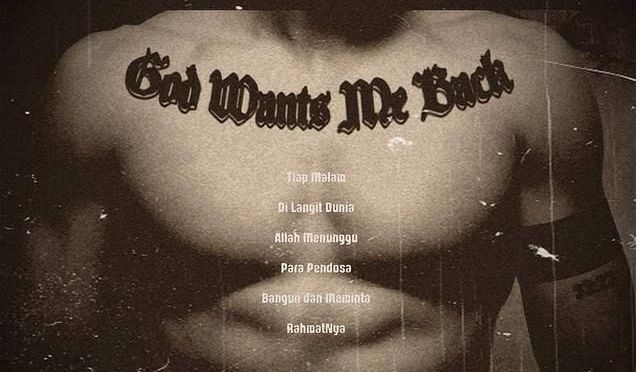

Their message to these kids, fine-tuned over the past three years, is that there is more to life than partying and losing oneself in drugs, alcohol, and other worldly intoxicants. Pemuda Hijrah offers them a community that accepts them as they are, tattoos and all, and helps them to reconcile an active social life with a meaningful spiritual life. Fun—a dangerous and radicalising substance—is encouraged. The group’s slogan is “Lots of play, lots of benefit, lots of merit … little sin”.

HANAN ATTAKI (L) WITH OUTGOING WEST JAVA GOVERNOR AHMAD HERYAWAN (CENTRE) (PHOTO: @HANAN_ATTAKI ON INSTAGRAM

Only Bandung could have produced a movement quite like this. With a population of around 2.5 million, and millions more in the greater region, the city has the most vibrant youth culture of any urban centre in Indonesia. The scene comprises many flourishing and interlinked sectors including indie music, graphic design, indie clothing production, and event organising—all permeated by a strong DIY ethos. Bandung also hosts the largest motorcycle gang scene in the country, with some members of the two main gangs, Brigez and XTC, migrating to Pemuda Hijrah in recent years.

The Pemuda Hijrah strategy is to package the street credibility and counter-cultural capital from these recruits into witty posters and sharp videos that appeal to mainstream middle-class youth online. These secondary recruits, many of them university students, are the primary market. Online recruitment also gives the movement its reach beyond Bandung. If these recruits are not members of a cool community before Pemuda Hijrah, they are now.

PHOTO: @PEMUDAHIJRAH ON INSTAGRAM

Pemuda Hijrah organisers are straightforward about how they align their brand with their target market. One founder, Fani Krismandar (known as Inong), told me that Pemuda Hijrah’s approach to branding is “a combination of Madina and Hollywood”. But it’s not all superficial marketing. Inong is representative of the group’s core team, he himself having found the mosque via the street: before his awakening he enjoyed a national following as a skateboarding icon.

What’s the difference between Pemuda Hijrah and previous Islamic movements featuring celebrity preachers? Although there are some similarities, Pemuda Hijrah is built less on the cult of celebrity than on the camaraderie of common interest. Key to Pemuda Hijrah’s success is that its recruitment model starts with a youth hobby group; the spiritual dimension is then affixed to that base and modified as needed. The result is some kind of globalised hybrid, with many elements repurposed from the Middle East. The process is the opposite of mainstream religious organisations like Nahdlatul Ulama and Muhammadiyah.

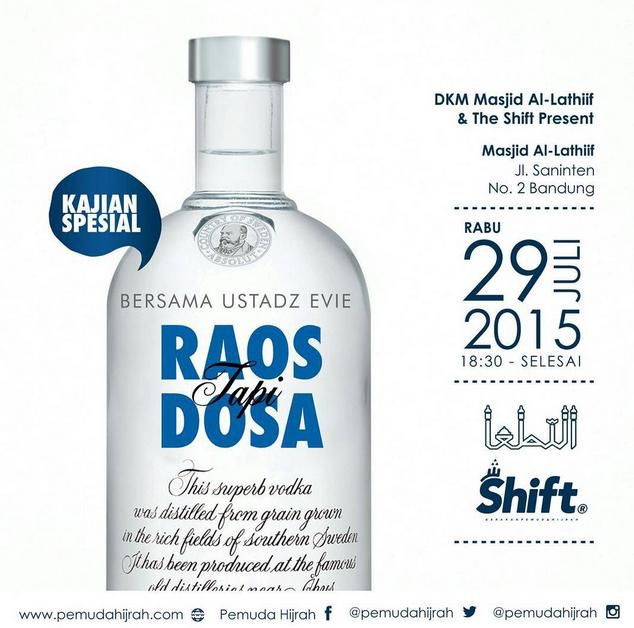

Also in contrast to other religious groups, Pemuda Hijrah preachers position themselves not as didactic authority figures dispensing advice from on high but as cool friends who stand in generational solidarity. This role is performed effortlessly by Evie Effendie, a popular preacher and former member of the Brigez motorcycle gang, who is known for his Sundanese-inflected wit. The title of his first book is “Gapleh”, one of his many coinages, which is an abbreviation of “gaul tapi saleh” (“social but pious”).

PHOTO: @PEMUDAHIJRAH ON INSTAGRAM

Pemuda Hijrah makes deft use of social media metrics to tailor its messaging. On Instagram, its largest cohort of followers is women aged 18-24 so “ladies nights” are a regular feature at Al-Lathif, their main mosque. Inong says they’ve identified the three most popular event themes: falling in love, finding a career, and hanging out.

HANAN ATTAKI (PHOTO: @HANAN_ATTAKI ON INSTAGRAM)

But love is the master theme.

In his sermons, Hanan Attaki, having long exchanged his kopiah for a beanie, drifts from preaching to Qur’anic recitation in an enchanting tenor voice. His ironic analysis of the social construction of Indonesian ghosts—why so many take the female form—sounds like feminism of a kind. At their crowded events, Pemuda Hijrah figures are perhaps slightly conscious of enjoying a loophole in the system: while women might dress modestly so as to not inflame the passions of men, there is much less done to avoid the reverse scenario.

Is there a dark side to Pemuda Hijrah? Like most revolutions, there probably is. The group is at the centre of a broader hijrah movement that can be traced to the underground music scene in Jakarta circa 2010, one which saw several prominent musicians disavow music in order to conform to a strict Salafist interpretation of Islam. There is a lengthening spectrum of groups and splinters in the hijrah movement, each with different ideas about to what extent followers should seek refuge from this corrupt world.

For its part, Pemuda Hijrah, which also goes by the brand name “Shift”, has emerged from the early debate over whether music is halal with a finely calibrated balance of contrast between the here and the hereafter. Too Salafist and they risk losing popular appeal; too popular or commercial and they risk losing spiritual credibility.

Who knows what direction the movement will go in the future, but one telling difference between Pemuda Hijrah and Salafist groups in Indonesia is that while the latter enjoin the use of Arabic terminology, Pemuda Hijrah favours English or, more precisely, the utopian idiom of Instagram: “no judgement”, “life goals”, “love lasts forever”.

Piety, politics, and the popularity of Felix Siauw

An ethnic Chinese convert to hardline Islam stands out in Indonesia’s crowded Islamic preaching market.

Quick counts indicate the election was won by the less conservative figure of Ridwan Kamil. But an unexpected late surge in votes for Sudjrajat–Ahmad Syaiku, putting the low-polling team in striking distance of the governorship, has led to speculation that hijrah networks helped to shift the vote. If so, West Java suggests a potential campaign model for a Gerindra-PKS coalition in the 2019 presidential elections—if these parties can harness the social media skills and networks of the hijrah movement.

Could Indonesian civil society learn from the Pemuda Hijrah example? It’s early days, but at least one group on Instagram imitates their style and even hijacks the #pemudahijrah hashtag. Unfortunately, the group follows ISIS and uses its platform to circulate videos that attempt to make interesting the statements of recently convicted Jamaah Ansharut Daulah leader Aman Abdurrahman. Not the kind of capacity building that many, least of all Pemuda Hijrah, would welcome.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss