Indonesians love a good conspiracy. Just check out the sales table on any mainstream bookstore like Gramedia, or the display racks of used-book street stalls, and you’ll find hidden truths and uncovered secrets of all kinds: the worldwide ones involving the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, the Illuminati, and the Rothschild banking family, as well as more Indonesia-specific ones about the puppetmaster behind the 30 September 1965 intrigue, Indonesia as the true location of Atlantis, and how Borobudur was built by King Solomon. In some cases, conspiracy theories can have a strong influence on how Indonesians interpret and respond to an unfolding crisis, such as during the witch-hunts that occurred in 1998 in far-east Java.

Hunting and killing ninjas in Indonesia

A troubling tale of sorcerer killings and ninja fear in East Java.

I argue that conspiracy is a paradigm through which some Indonesians view their past. For want of a more imaginative term, we might call it conspiracy history. This is not something unique to Indonesia; see, for instance, Liam Hogan’s work on debunking the Irish slaves conspiracy history. But in Indonesia’s case, it has a lot to do with how Suharto’s New Order dictatorship (1966 – 1998) attempted to control history, and with the post-1998 efforts to revise and rectify the historical narrative.

Conspiracy history in Indonesia results from two things: 1) the impoverishment of critical historical skills that is a legacy of the New Order education system, and 2) a genuine desire to overturn the orthodox historical perspectives imposed by that regime. This ambiguity makes conspiracy history a valuable topic of study, because it shows us what happens when people yearn for new perspectives on the past, but don’t have the resources or skills to mount a valid historiographical challenge to the status quo.

Gaj Ahmada and the Sultanate of Majapahit

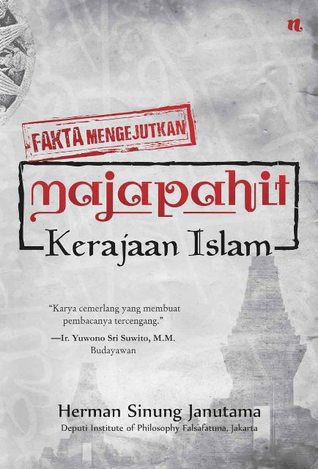

My case study is a conspiracy that is noisily making the rounds on social media at the moment: the claim that the East Javanese kingdom of Majapahit (14th – 15th c.) was a Muslim sultanate, and that its most famous prime minister, Gajah Mada, was a Muslim called Gaj Ahmada. This conspiracy challenges the generally-accepted view that Majapahit was ruled by Shaiva Hindu and Mahayana Buddhist monarchs. The conspiracy historians claim that the main textual source for this orthodox Majapahit history, the Pararaton (“Book of Kings”), is actually a forgery written in 1896 by the Dutch scholar JLA Brandes.

Both the Dutch colonial government and the Indonesian national government, so the conspiracy historians say, perpetuated the falsehood that Majapahit was a Hindu-Buddhist state in which Muslims were a small minority, mostly occupied as traders and courtiers, but not in charge.

Why would the governments lie about this? The conspiracy historians say that the authorities tried to hide the true Islamic nature of the Majapahit kingdom in order to marginalise the Islamic political movements of their own time.

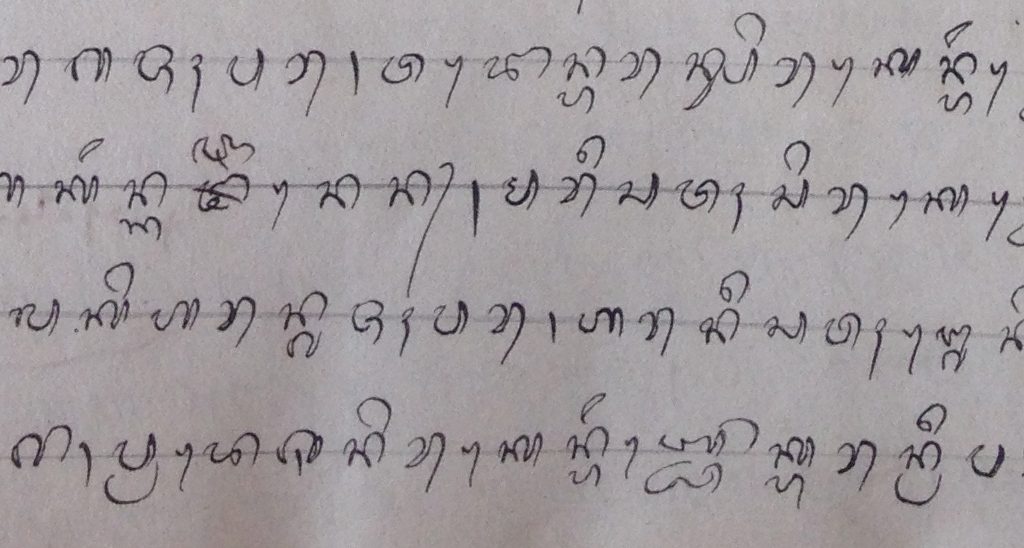

Needless to say, this conspiracy history has no evidence to support it. All of the Majapahit-era inscriptions, which date from 1294 to 1486 and deal directly in religious matters, indicate that the royal court patronised both Hinduism and Buddhism, as well as a network of rural ascetics called resi, but definitely not Islam. Communities of Muslims did exist in the capital and in the large trading cities on the north coast, as demonstrated by Muslim gravestones and by the contemporary reports of visiting Chinese Muslims, but they never controlled the kingdom. The authenticity of the Pararaton, which describes the Hindu and Buddhist character of the Majapahit kingdom in depth, is well-attested by the dozens of manuscript copies of the text found throughout Bali.

Majapahit as Proto-Indonesia

So why is Majapahit, a kingdom that disappeared 500 years ago, the topic of a major Internet conspiracy today? The primary reason is the role of Majapahit in the development of Indonesian nationalism. The generation of politicians who led the country’s independence movements were concerned to find a historical basis for a united Indonesian nation. Faced with the diversity of languages, customs and religions in the archipelago, one of these leaders, Muhammad Yamin, turned to the premodern past to find powerful states that he could claim to be precursors of modern Indonesia. Yamin chose Majapahit, the region’s most powerful state in the 14th century, as one of these precursors.

Since then national history textbooks have asserted that the territorial extent of the Majapahit empire closely matched Indonesia’s modern borders, an incorrect claim that is based on a deliberate misreading of a Majapahit-era poem called Desawarnana. Yamin, and most Indonesian historians since, have claimed that unification of the archipelago was a fundamental political goal of prime minister Gajah Mada, just as it is of the modern Indonesian state. Gajah Mada’s mysticism and militant imperialism provided a personal role model for Suharto himself. The identification of Majapahit and Indonesia went so far that a quotation from another Majapahit-era poem called Sutasoma was picked as the national motto: Bhinneka Tunggal Ika (usually translated “Unity in diversity”, but more accurately “They are separate, they are one”).

So a conspiracy about the state religion of Majapahit strikes at the question of the religious identity of the modern Indonesian state. The Gaj Ahmada conspiracy is used to argue that Islam should play a much greater role in the Indonesian state than it currently does. Ever since the first official deliberations on the Indonesian constitution and state philosophy in 1945, a significant minority of political leaders have advocated for a greater role for Islamic principles in the nation’s public life. This religiously-oriented faction has never really prevailed in the political arena, where quasi-secular nationalism has long been the dominant force.

Since Majapahit is widely seen as a prototype for Indonesia, the revelation that Majapahit was actually an Islamic sultanate would give a boost to those who would see Indonesia take on a more Muslim character. Earlier this year, a political campaign against the recently-defeated governor of Jakarta, a Chinese Christian, made the claim that a Qur’anic verse forbids Muslims to accept a non-Muslim ruler. So if it turns out that the Muslim communities living in Majapahit were ruled not by Hindus and Buddhists but by fellow Muslims, then the 14th-century history of Majapahit can be made to support a political agenda in 21st-century Indonesia.

Revision or Conspiracy?

To push this agenda, the conspiracy historians have to attack the credibility of the mainstream historical account. Many Indonesians are already highly skeptical of the versions of history they are taught in school, because of the way the Suharto government grossly manipulated history education. This is fertile ground for conspiracy history, because the Indonesian government really did try to cover up truths about the past, and in some cases, it still does. The line between genuine revisionist history and conspiracy history becomes blurred, because the conspiracy historians imitate the language of revisionism: ‘Straightening Out the History of Majapahit’, ‘Surprising Facts! Majapahit, A Muslim Kingdom’.

It is difficult for general readers to distinguish between an informed alternative view and a conspiracy history. This is because of the way history is taught in schools: it is presented primarily as a set of true facts about the past, while the study of primary sources and historical method is supplementary. Students are encouraged to comment on the information provided by the textbook, rather than being trained to develop their own arguments based on historical evidence.

It is difficult for general readers to distinguish between an informed alternative view and a conspiracy history. This is because of the way history is taught in schools: it is presented primarily as a set of true facts about the past, while the study of primary sources and historical method is supplementary. Students are encouraged to comment on the information provided by the textbook, rather than being trained to develop their own arguments based on historical evidence.

This means public debates about history are often reduced to a conflict between different accounts, each claiming to be the most accurate version. Since their school textbooks do not familiarise them with the primary sources of Majapahit history, non-expert readers are in a quandary when those textbook interpretations come under attack. The credibility of the historian, rather than the strength of their argument, becomes the criterion for the reading public to decide who to believe. This need for credibility is why the conspiracy historians copy the rhetoric of genuine anti-mainstream revisionism, despite the fact that their works meet none of the professional standards of historical research.

From Conspiracy History to Public History

The conspiracy historians who say that Majapahit was a Muslim sultanate are wrong, but they are not crackpots. The readers who believe and share their work are wrong, but they are not stupid. Both are products of the particular conditions for history-making in Indonesia today: skepticism towards official versions of history, reluctance to give up on the nationalist paradigm, a history education system that is content- rather than skills-focussed, and an impulse to ground contemporary political debate in historical precedent.

Despite all this, I think there is some cause for hope. Skepticism is a good basis for critical thinking in general. The Gaj Ahmada conspiracy history has not gone unchallenged, but provoked strong rebuttals from experts that are being shared widely. The online debate has put issues of historical evidence and method at the front of the public’s mind, and several large Facebook groups have hosted serious, informed discussions about Majapahit history. An optimist might imagine that as Indonesians become used to seeing conspiracy histories get publicly debunked, they will pick up the critical historical skills that their school education does not offer. The result could be a genuinely public history to displace the state-controlled national history of the past, and the groundless conspiracy histories of the present.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss