What do Papuan politician Yorrys Raweyai and Muammar Gaddafi have in common? Yorrys ran for a seat in the national legislature for Golkar and lost. Muammar is a young United Development Party (PPP) member who stood for election to the local council in Bekasi, West Java and also did not get elected. They both complained to the Constitutional Court (MK) that it was fellow party members who stole their votes.

And they are not alone. Perludem researchers found 118 of the 716 complaints* brought to the MK by the parties after the 9 April legislative elections related to internal disputes created by the open list proportional representative system. Scrutiny has already started and perceived problems with the open list will bring this method of voting under fresh scrutiny as the new DPR again revises the election laws.

Since 2009, Indonesians have been able to vote for either a party or a candidate. This came about after a 2008 decision by the MK that declared unconstitutional the partially open party list system that was practiced in 2004 and was planned again for 2009. [UPDATE: The court objected to the fact that candidates could gain a seat despite having less votes than their intra-party competitors – i.e. when the quota remained unfulfilled and therefore the party ranking was applied]. It was a late ruling given that preparations for the polls were already well underway and most candidates were unaware of its implications. While open lists are used in Brazil, Denmark, Chile, Finland, Iraq, the Netherlands and Sweden among others, the 2014 elections were the first full cycle where this system was used in Indonesia.

There are pros and cons to open and closed lists. A 2013 Asia Foundation/Polling Center survey found political party backing an insignificant factor in voting preference, with just over 11 per cent saying this was important when choosing a legislative candidate. A 2010 Kemitraan/IFES survey found 77 per cent of Indonesian voters preferred to choose a candidate to represent their community rather than a party. In the April 2014 election, 70 per cent directly chose a candidate. But analysts have long feared that the open list system would open up the electoral process to new kinds of corruption by forcing candidates to compete against members of their own party.

The Asia Foundation’s Hana Satriyo wrote in April on New Mandala that female candidates would be particularly vulnerable to having their votes stolen and this would lower their numbers leading to a push for a return to the a closed proportional system. The International Republican Institute, which worked with hundreds of women candidates across five provinces, said in a post-election analysis women have historically had less money and internal party support than their male colleagues “this puts them at a severe disadvantage” in an open list.

Supporters of an open list system in Indonesia argue that when political parties are weak and corrupt, the open list forces candidates to build direct relationships with constituents rather than buy their way onto the top of a ticket by paying off party bosses. It might mean that fewer bribes go to party officials but more money is spent on “money politics” or buying votes. This drives the ground war that Ed Aspinall wrote about on these pages a few weeks back when he asked why the so-called Jokowi effect was limited. Opponents of the open list system counter that it undermines parties as institutions and the useful role they play in combining and channelling diverse aspirations. Open lists, some say, also confuse voters by overwhelming them with candidates they might never have heard of.

The MK complaints highlight the prevalence of apparently corrupt practices being used by individual candidates and their supporters, possibly with the connivance of party officials, to gain an advantage over rivals from within the same party by working with dishonest polling officials to alter results. This requires greater scrutiny by election authorities, supervisors, and parties as well as by the media and researchers.

Often there is a difference between the votes recorded as being cast at the polling station and recorded on the ‘C1’ forms with the numbers put against the same polling station when the votes from dozens of locations are consolidated at the sub-district and district levels. When these numbers do not add up, candidates complain.

[UPDATE: As Marcus Mietzner points out, only parties could file complaints. The fact that Yorries’ complaint is heard must mean that he convinced Golkar to file the claim in his name. Or it could mean that Golkar decided that it didn’t want to deal with it and thus submitted it for arbitration by the court. In any case, more questions need to be asked why parties file complaints for some candidates but refuse to do so for others?]The differences can be as small as one or two votes per polling station. In some cases, through the addition or subtraction of one digit, it can involve variations of hundreds or even thousands of votes. Where the difference is small, it could well be the result of tabulation or transcription errors, but most complaints alleged these mistakes are a result of manipulations by unnamed election officials. In some cases, witnesses have testified in the MK that C1 forms never made it to the polling stations for party poll witnesses to sign. Sometimes, officials were caught stuffing ballot boxes and photographed doing so on hand phones.

No matter how small, the complainants argue that these votes all add up and at the local level they can make a difference. After the local election commission (KPUD) in Bekasi declared H. Kairan to be the elected legislator for PPP, Muammar asked the MK to confirm that the actual count was 3,923 votes for him and only 3,907 for H. Kairan–a margin of only 16 votes.

Yorrys, a serving national legislator and number one on the Golkar ticket in Papua province, claimed that 51,132 votes that were meant for him were distributed to other candidates, including 25,107 that went to the official Golkar winner Pastor Elion Numberi. In the same constituency, another Golkar candidate, Agustina Basikbasik, alleged that 100,000 votes were taken from her by Yorrys and Elton by someone removing one digit from her count. Her complaint says she should have received 115,579 votes rather than 15,579. Samsudin Manja claims says some 20,000 of his votes went missing and a fifth candidate from the same party list, Paskalis Kossay, claimed 30,000 of his votes were stolen. Making all the numbers add up will be the court’s challenge. (The huge numbers may also reflect the impact of the noken system of proxy voting that leads to whole polling stations, sub-districts or kabupaten being captured by one candidate).

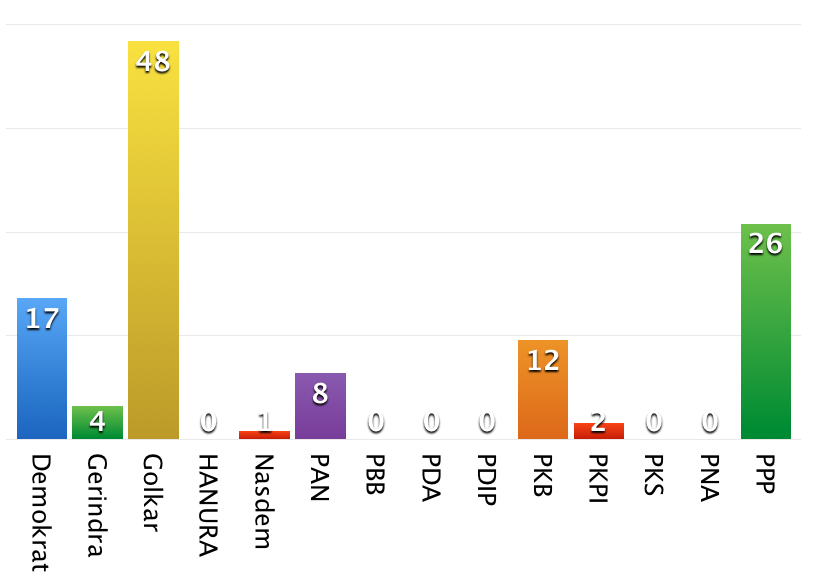

The 2014 petitions to the MK are illustrative but an incomplete data set. Seven parties did not report any disputes with some stating they had not allowed individual candidates to complain, including Gerindra and PDI-P. PDIP’s secretary-general Tjahjo Kumolo even jokingly referred to these internal cases as “Kekerasan Dalam Rumah Tangga or KDRT” or cases of domestic violence that would be handled out of the public eye.

Numbers of internal party disputes brought to Indonesia’s constitutional court in 2014 (Source: Perludem analysis)

But the internal tussles do spotlight a few issues. They are a subset of the larger number of cases of manipulation during the recapitulation process. Perludem’s initial analysis calculates that almost 60 percent of complaints regard the “inflation or deflation of votes”. Recapitulation is one area where there is much room for improvement in the election system. But there is some good news as online publication of polling station results has been used by aggrieved parties to build their cases. Ensuring greater compliance with the posting of these forms for the presidential poll might be a first step to improving transparency.

The MK complaints show that intra-party conflict is a significant issue and the open list system exacerbates it. While some women candidates have alleged theirs votes have been taken by male colleagues, men have also claimed that women candidates wearing the same colours have benefited from these manipulations at their expense. This problem deserves much closer study and not just as a gender specific issue.

In the meantime, the MK cases are shedding more light on the complicated local relationships required to get elected, not only with constituents but with party officials and local power holders. The court hearings began on Friday (23/5), and as they proceed transcripts will be appearing on its web site. Judges must rule on these 716 cases and publish their verdicts by 30 June. As they do, questions will be raised about the way politics is played in Indonesia, adding momentum to the reform agenda. Compared to 2009, this is a better but not perfect election. But there is still much to improve about Indonesia’s electoral system.

*This is higher than our initial analysis because in contravention of the law the MK later accepted an additional 14 cases after 12 May deadline.

……………

Jim Della-Giacoma is a Visiting Fellow at the Australian National University’s College of Asia and the Pacific, School of International, Political, and Strategic Studies in the Department of Political and Social Change. Follow him on Twitter at @JimDella

Veri Junaidi is the Deputy Director of Perkumpulan Untuk Pemilu dan Demokrasi (Perludem) and the author of Mahkamah Konstitusi Bukan Mahkamah Kalkulator (Themis Books 2012). Follow him on Twitter at @VeriJunaidi

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss