Late one November night in 1946, the owner of the villa at 89 Rue de Verdun wrote a final letter. He then tied a noose to the rafter in his upstairs bedroom.

The suicide of Nguyễn Văn Thinh left vacant both this Saigon villa and the Republic of Cochinchina’s presidency. From June to November that year, the villa was both his home and seat of government for this ill-fated, French-sponsored state. French officials had denied him Norodom Palace—the centre of the colonial state and later site of South Vietnam’s presidential palace, renamed as the current tourist attraction “Independence Palace.” But Saigon’s first presidential palace remains today, unadorned and unvisited, at number 89 on the renamed August Revolution Street [Cách mạng Tháng 8].

Today, the Vietnamese state tells visitors that Independence Palace memorialises the leadership of the communist party in realising Hồ Chí Minh’s aspiration. The villa at 89 August Revolution Street, however, is a countervailing monument to the diversity of leadership within Vietnam’s late colonial society and the alternative aspirations for political development that many Vietnamese supported.

Nguyễn Văn Thinh saw the Republic of Cochinchina as a means to counter that Việt Minh-led revolution in August 1945, which he judged extremist and disorderly, and to stop France from re-colonising Cochinchina after World War II. He and his ministers publicly advocated for “Franco-Vietnamese collaboration” as a means to establish a democracy in Cochinchina while seeking independence for Vietnam under a more moderate political system than the Việt Minh.

Nguyễn Văn Thinh was at once an anti-colonialist and a counter-revolutionary, a republican above all. Those were traits ill-suited to a moment dominated by colonialists and revolutionaries. French officials saw a threat to their privilege and plotted his removal. The Việt Minh accused him of being a French “puppet” for cooperating in the establishment of a Cochinchinese state that undermined the Việt Minh’s claim to a unified, national state. His death was an admission that the Republic of Cochinchina and his lifelong pursuit of republican reform in Vietnam’s colonial society had failed.

Colonial politics

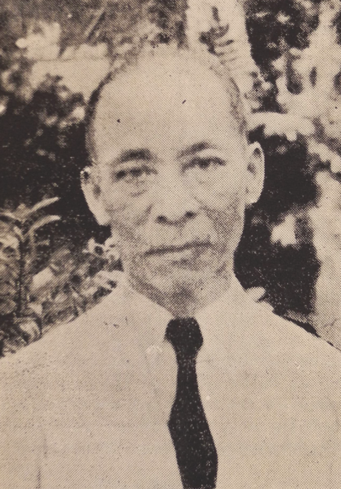

Dr Nguyễn Văn Thinh in 1946. (Photo: Tiểu sử Bác sĩ Nguyễn Văn Thinh/Biography of Dr. Nguyễn Văn Thinh [Saigon: Imprimerie de l’Union, 1947])

Upon his return to the French colony of Cochinchina, Nguyễn Văn Thinh acted on those principles as an elected member of the Colonial Council. He and his political allies advocated for Indochina’s states to possess economic and political autonomy and remain bound to France “only by a tie of deferential affection.” He sought to increase Vietnamese representation in administrative and political institutions. In his spare time, he published European medical information in vernacular Vietnamese texts. He was an active Freemason, and though a landowner, he supported lowering the tax burden on the peasantry and denounced senior Council members’ compromising commercial interests.

By the standards of the time, he was a progressive politician. Saigon’s leading Trotskyist, Tạ Thu Thâu, worked with Nguyễn Văn Thinh to demand colonial reforms. Vietnam’s Stalinist communists attempted to form a popular front with Nguyễn Văn Thinh’s Indochinese Democratic Party in the late 1930s, reporting to Moscow that they were “progressive capitalists” favouring “radical/progressive reforms.”

The August Revolution

For Nguyễn Văn Thinh and many others, the Việt Minh’s seizure of power in August 1945 felt less a moment of liberation than one of violence and disorder. Among those executed by the Việt Minh were colleagues and friends of the doctor. He then watched as French forces, displaced by Japan during the war, returned in September 1945 and violently expelled the Việt Minh from Cochinchina’s cities to reoccupy their former colony.

By early 1946, Nguyễn Văn Thinh began advocating publicly for a revival of Franco-Vietnamese collaboration and an Indochinese federation, with each of Vietnam’s three regions (Cochinchina, Annam, and Tonkin) possessing their own autonomous republican government akin to Australia and Canada’s status within the British Commonwealth. The doctor was building upon the promises that Charles de Gaulle had made for a new French Union in 1945. But in practice, French officials sought to neutralise dissent and operate a neo-colonial federal administration over all of Indochina that would foil the Việt Minh’s claim to a unified Vietnamese state. French colonials similarly wanted to turn Cochinchina into a département within the French Union, rendering it French soil subject to French rule. To them, Nguyễn Văn Thinh seemed the perfect collaborator. The Republic of Cochinchina appeared the perfect vehicle.

Republic of Cochinchina: separatism or unity?

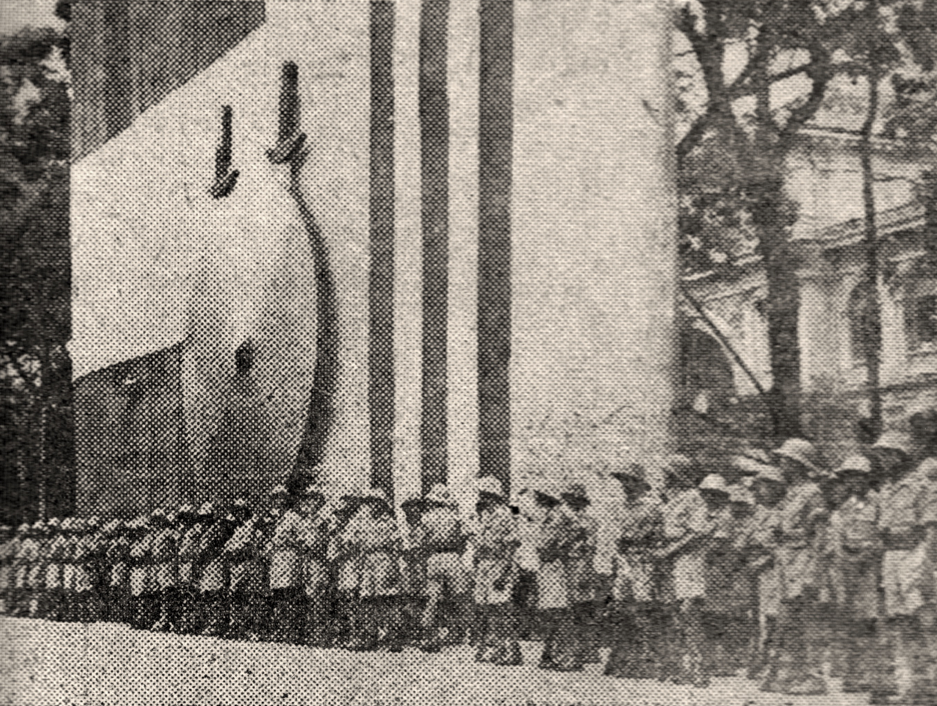

View of the inauguration of the Cochinchina Government with Vietnamese members of the Republican Guard beneath a French flag and the Republic’s yellow flag with three blue stripes. Saigon’s main post office is in the background. (Photo: Tân Việt [Saigon], 1946)

For his part, Nguyễn Văn Thinh maintained a technocrat’s demeanour and abstained from political discourse. Unable to publicly denounce French colonialism or support a unified Vietnamese state, he was only capable of recruiting aged or conservative figures, like the colonial-era politician Nguyễn Phú Khai and famous novelist Hồ Biểu Chánh. Others, including his friend Dr. Nguyễn Văn Hưởng—later Minister of Health in Hồ Chí Minh’s government—rejected his offer and warned: “You are going against the course of history, please reconsider.”

Publicly, Nguyễn Văn Thinh adhered to the motto of “Franco-Vietnamese collaboration” that secured him support from the French colonial establishment. Privately, however, he believed he could reach the same ends as Vietnam’s nationalist revolutionaries without the violence he abhorred. When members of the Việt Minh appealed to him with their platform, Nguyễn Văn Thinh replied: “I agree with your policy. But I am not fond of your methods and actions.” He explained the necessity of collaboration with France when speaking to the editor of a newspaper critical of the Republic: “Nowadays, we simply accept one of two solutions. Either we get departmentalised [as a French colony] or we accept autonomy with a government that is detached from the Hanoi government.” The Republic, he argued, “despite it falling short of independence and unified freedom, is better than becoming a département.”

The French security services’ spies reported that Nguyễn Văn Thinh told his cabinet their motto was to be “Ne vendez pas la Cochinchine aux Français” [“Do not betray Cochinchina to the French”]. Another source still reported that the president intended to be the “Ho Chi Minh du Sud,” winning independence for Cochinchina first, then seeking to unite all three Vietnamese regions in a federation of local and national parliaments where suffrage would be universal for men and women.

The Republic and its opponents

For the Việt Minh, Nguyễn Văn Thinh and his Republic were French collaborators and threats to their sovereign claim. This rival state sentenced the doctor to death for treason and attempted to carry out the verdict in three failed assassination attempts. The Việt Minh were successful in assassinating a Vietnamese member of the Cochinchina Council and writers at the few Saigon newspapers supporting the Republic.

French officials proved an equally daunting adversary for Nguyễn Văn Thinh. Soon after the Republic’s June inauguration, Governor General d’Argenlieu and his political counsellor Jean Cédile began to realise that Nguyễn Văn Thinh sought a genuinely independent state. Cédile insulted Nguyễn Văn Thinh as a “lowly orderly,” complaining of his “hostility” toward the French, and his refusal to sign an agreement codifying France’s control over the Republic. Throughout the summer, Cédile systematically thwarted the president’s efforts to acquire American and British materiel, aid, and expert advice.

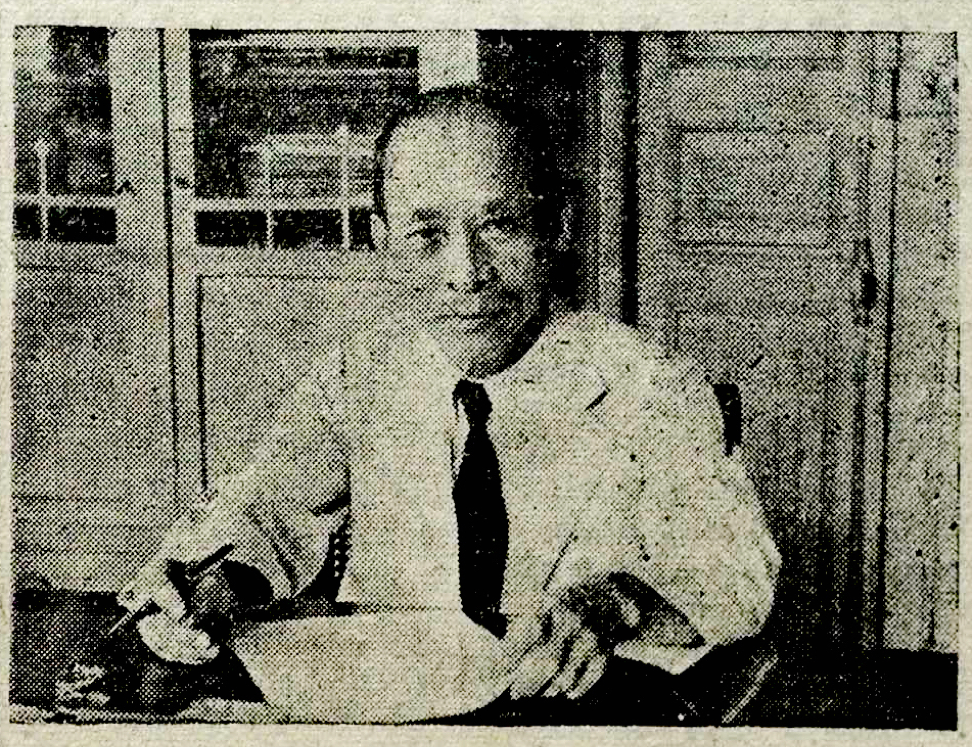

Nguyễn Văn Thinh seated at his desk in 1946. (Photo: Tân Việt 1946)

The president also struggled with the 14 French members of the Cochinchina Council (there were 28 Vietnamese), appointed by d’Argenlieu. By September, the French had turned on Nguyễn Văn Thinh’s cabinet. They accused members of being pro-Việt Minh and undermining French sovereignty. One French member declared at a council meeting that “it would be preferable to negotiate with Hồ Chí Minh,” rather than Nguyễn Văn Thinh’s government. Their anger was matched by Cédile, who told d’Argenlieu that it was time to orchestrate the president’s downfall.

Vietnamese Council members also grew impatient with the Republic’s leadership. They demanded the suppression of newspapers and journals that supported the Việt Minh. Instead, the Republic chose not to enforce press censorship that the colonial state had implemented, and which their counterparts in the Việt Minh continued to exercise. Nguyễn Văn Thinh and his vice president insisted that a free press was necessary in a democracy. “The truth triumphs always,” they retorted. They pledged to win the public’s support through their actions. For all its flaws, the Republic oversaw the era where Vietnamese enjoyed their greatest press freedoms, then or now.

Yet by November, the Republic was unable to act: opposed by French officials, the Việt Minh and their many sympathisers, and Council members demanding stronger action. At a Council session on 7 November, Nguyễn Văn Thinh laid these problems at the feet of France, who he charged with operating a hybrid state in Cochinchina. “Is it a colony or a Republic?” he asked the members. A French delegate broke in and answered the question without addressing it. He read aloud a note from d’Argenlieu’s office, stating that the French administration favoured a new cabinet within the week. A vote of no-confidence passed 26–3.

Death of the Republic of Cochinchina

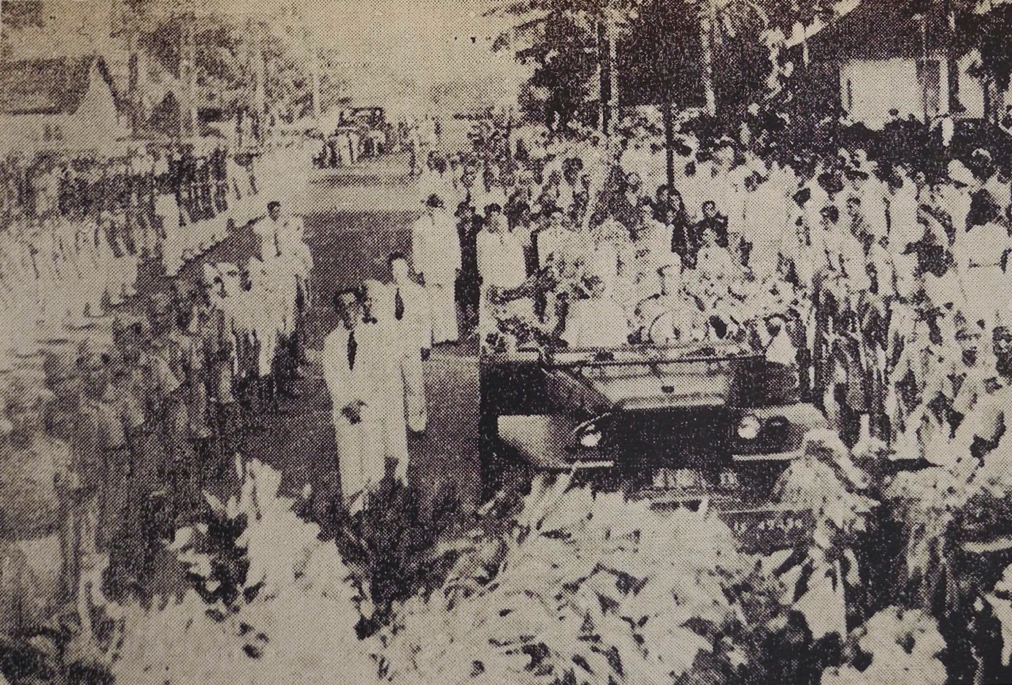

Nguyễn Văn Thinh’s funeral procession travels in front of Saigon’s botanical gardens and zoo. (Photo: Tiểu sử Bác sĩ Nguyễn Văn Thinh/Biography of Dr. Nguyễn Văn Thinh. [Saigon: Imprimerie de l’Union, 1947])

In death, Nguyễn Văn Thinh revealed his belief in a unified Vietnam and, for the first time, warned of the Việt Minh’s Stalinist leadership that had purged its nationalist rivals weeks earlier. In his suicide note, he implored “you my friends, the intellectuals of centre, south, and north,” to establish an alternative political regime to the Việt Minh. Breaking his political silence, he concluded with a final warning: “I die to denounce the dangers of a menacing red dictatorship.”

The menacing dictatorship that he warned of would succeed in taking leadership of the Vietnamese revolution and, ultimately, a unified Vietnamese state. Yet the failure of Nguyễn Văn Thinh’s republican state project should not obscure the diversity of Vietnam’s political life, or the alternatives pathways that Vietnamese sought out of colonialism.

France’s actions undermined the Republic and the model of republican reform that Nguyễn Văn Thinh had advocated for his whole life. By contrast to India, where late-colonial British rule empowered Indian reformers, France discredited the political moderates in Indochina. Had the Republic been empowered in 1937 when he founded his Indochinese Democratic Party, the outcomes probably would have been very different. But even in failure, his state project gave rise to new alternatives.

Emboldened by his death, Vietnamese supporters of the Republic publicly disavowed the French administration’s plan for Cochinchinese “separatism.” The Republic’s leaders supported a unified Vietnam, led by former emperor Bảo Đại and in cooperation with the nationalist parties purged by the Việt Minh.

It would take another two years before France agreed to inaugurate this new, unified State of Vietnam [Quốc gia Việt Nam] that spanned the whole country. Like the Republic, the leaders of this state also sought to work through France to eliminate colonialism. But it too would become a failed state project, stricken by all that ailed the Republic of Cochinchina. Undermined by French colonial officials, the State of Vietnam would only obtain its full sovereignty when France withdrew after the 1954 Geneva Accords and Ngô Đình Diệm oversaw the state’s consolidation below the 17th parallel as the Republic of Vietnam.

This article is based on a chapter of the author’s PhD dissertation, which can be found on his website.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss