Anyone who still has doubts about the political role of Thailand’s monarch may find this extraordinary puff piece from AP worth reading (especially in combination with the recent piece by Michael Montesano). Here are some extracts:

BANGKOK (AP) – As Thailand’s ailing king surveys the calamitous scene from his 16th floor hospital window, the 83-year-old monarch encounters an element that has challenged, virtually obsessed, him most of his life: water.

It’s rising around him, the floodwaters sweeping through Bangkok and overflowing the banks of the Menam Chao Phraya, the River of Kings, that rushes right past Siriraj Hospital, where he has lived wheelchair-bound for the past two years.

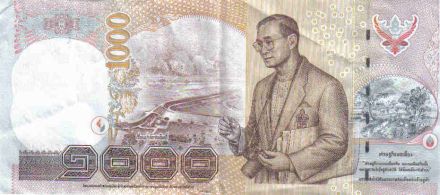

The flood, the worst in half a century, is something King Bhumibol Adulyadej has tried harder than perhaps anyone to prevent. He has sounded alarm bells – not always heeded – against overdevelopment and come up with ideas that have mitigated the damage from the immense annual surges and retreats of monsoon-spawned water. …

Even now, as the Thai capital and its environs fight the onrush, the world’s longest reigning monarch is offering advice on how best to channel the unprecedented buildup of water from northern highlands into the sea. But unlike times past, the constitutional but powerful monarch is unable to undertake inspections or cajole, sometimes reprimand, ineffective bureaucrats into action.

Heir to a legacy of Thai kings who saw the controlling of water as a royal task, one of Bhumibol’s first development projects was a reservoir in 1963 to trap fresh water and prevent salt intrusion in the seaside resort of Hua Hin. Today, these royally initiated projects number more than 4,300, with 40 percent related to water resources.

“The king’s ideas, proposals and implicit or explicit stamps of approval can be detected throughout Thai water resource management policy and practice of the last 40 years at least,” says David Blake, a water expert at England’s University of East Anglia who has studied the issue in Thailand. …

The king called his most notable move the “monkey cheeks” strategy, recalling from childhood pet monkeys which would munch on bananas, then retain the food in their cheeks to swallow later.

The water that yearly rushes down from the north is diverted into “cheeks” on the approaches to Bangkok, then flushed into the sea or used for irrigation. This involved construction of reservoirs as well as dikes, canals and water gates. Along with an improved drainage system in the city, it’s credited with mitigating floods in the 1990s and the past decade.

“We must use the wrath of nature as our teacher,” the king said in 1990. “If we can find a way to keep floodwater in reserve and to use it when it’s needed, it will be a double boon.” …

Since then, potential reservoir sites to the west, east and north of the city have been filled in for industrial parks, housing, golf courses and the international airport.

“The major cause of the flood is the fact that we built our houses on wetlands. My point is that humans have changed nature so much from what it used to be,” Bhumibol said.

As early as 1971, the king warned that massive logging of the great northern forests would trigger future floods. Deforestation, which reduces the land’s ability to absorb water, is today recognized as a contributor to the flooding.

Over the next two and a half decades, traveling to every corner of the country, Bhumibol set out to both harness and manage water, from draining swamps in the south to designing upland irrigation for indigenous hill tribes in the north. …

Not all of his ideas worked; in many cases, Blake says, the king’s inventions or principles weren’t carried out properly.

Bhumibol himself said he was just proposing “feasible ideas. Implementation must remain with those in charge. If they are misinterpreted or mishandled, they are doomed.”

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss