11 June to 16 July 202,

8 Llankelly Place,

Kings Cross 2011

RISE 2 adopts the format of a long essay to frame artists’ stories about rising sea levels and the raw kinetic power of water: ferocious, beautiful, hell-bent. The colour ‘blue’ in all its hues is emblematic of water. Blue as pigment emerged through the colonial impulse to extract resources such as alluring lapis lazuli and blue-green turquoise. In European art history, the cost of blue pigment conferred the colour the status of sublime highlight or vast horizon line.

Today’s seas are dark as rising water converges with global frames of ecocide, genocide, land rights, corruption and fossil-fuel mining: the oppressive outcomes of colonialism including present-day corporate colonialism. The artists are old-hands at depicting our unstable geopolitical region as their works eddy from art as awareness-raising poetics to tongue-in-cheek diplomacy to forensic analysis.

The waters of northern Australia, the Indonesian archipelago (Nusantara) and Torres Strait, are connected by powerful monsoonal currents and seasonal monsoons that join the busiest maritime waters in Asia. On a long-time scale, Papua was joined to Australia and the Gulf of Carpentaria was a freshwater lake. The big swamps and plains of Kakadu World Heritage Area and the plains around Jakarta were mangrove forests. Kakadu today is a rich fresh-water wetland, home to magpie geese surrounded by magnificent rock art galleries.

But the protective and stabilising coastal barrier of mangrove forests on the Northern Territory coastline, where half of Australia’s total mangrove area occurs, is failing. Jakarta is the fastest-sinking city on the planet, creating ever more vulnerable climate refugees. In the Top End, oil and gas extraction is known by the euphemism ‘Develop the North’. Australia is the third-largest fossil fuel exporter in the world behind Saudi Arabia and Russia and is belligerently expanding production. Indonesia is not far behind. Both countries offer fossil-fuel subsidies and/or tax exemption.

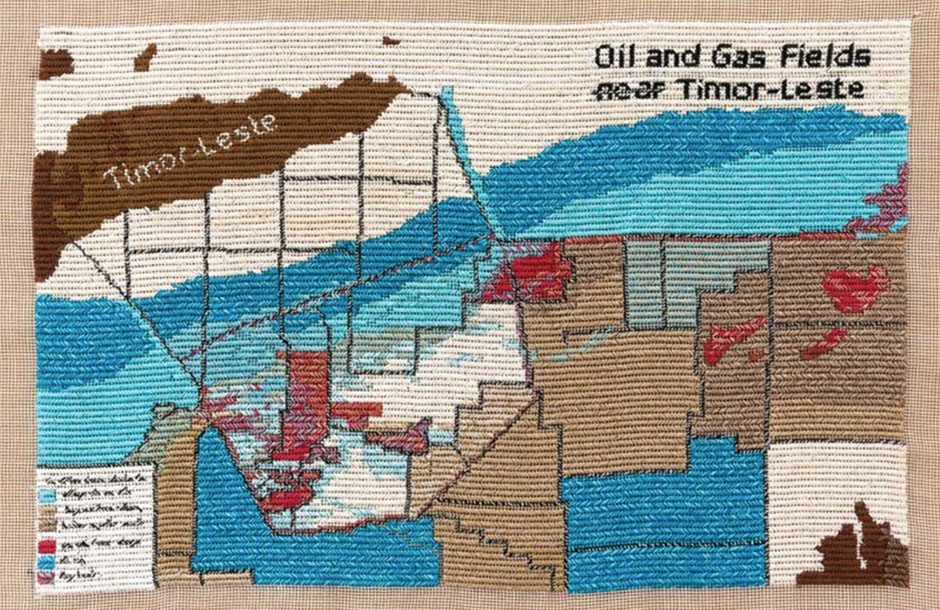

The shifting abstraction of Narelle Jubelin’s petit-point map of ‘Oil and Gas Fields Near Timor-Leste’ (2014) and Ucup’s densely inscribed woodblock banner, ‘Sri against the giant’ (2020), show the strangle-hold operation of arrogant power. The artists point the finger at corporate Australia and Indonesia (and their various foreign partners in crime) as reckless destabilising agents.2 Ucup says about ‘Sri against the giant’: ‘This artwork is dedicated to the people, specially women, where they still resist to government policy, asking for justice. They never stop and never give up against injustice’.

Just as astonishing are Fitri DK’s woodblock prints that target the horrors of West Papua (Papua Barat). She shows the Grasberg gold and copper mine (run by US mining-giant Freeport McMoRan), the mine’s destruction of a mountain sacred to the Amungme and Komoro people and toxic tailings flowing to the sea as a river of deathly-grey sludge.

Jubelin, Fitri D.K and Ucup use obsolete media and the language of the powerless and displaced underclass (petit-point and woodblock printing), to disarmingly engage with the dark politics of fossil-fuel extraction. Australia’s response to genocide in West Papua, is cynical: ‘Hear no evil, see no evil’, just as it was silent in 1975 on General Suharto’s invasion of Timor-Leste and the murder of Australian journalists.

Fitri DK, Derita Sudah Naik Seleher / Up to our necks with suffering, 2018. Woodcut print on paper, 80 x 60 cm, edition of 10.

In contrast, an artist-led campaign Papuan Lives Matter began as a hashtag on social media, spreading across the sprawling archipelago of 270 million people. Indonesians shared links to webinars and websites with information about human rights issues in West Papua. An Instagram post saying “We cannot talk about #Black Lives Matter without talking about West Papua” received more than 10,000 likes.

In Pennyrose Wiggins’s painting ‘Gasland’ (2020), on a discarded ‘Stop’ sign ant-like gas-miners work under a dark foreboding cloud as they drill into the Beetaloo Basin. ‘Gasland’ cites a documentary on the US fracking industry and its environmental anarchy and water contamination (2010 by Josh Fox). The corporate frenzy is global. Wiggins’s miners drill into the Tindall limestone aquifer which provides fresh water supply to nearby communities, agriculture and the cattle industry. Australia’s fresh-water aquifers are very limited and already heavily impacted by climate change.

Contemporary exhibition-making is rightfully dominated by artists’ observations, thinking and activism, aiming to highlight the cumulative impacts of continuing (and increasing) resource extraction. In grand surveys such as Rivus, 23rd Sydney Biennale (2022, curator José Roca), viewers made a venue-to-venue pilgrimage around tableaus of fragile local initiatives and undertakings.

Beyond borders at APT 10 Part 2: Textures & translations in SEA abstraction

Drawn from local contexts, these abstractions also transcend borders.

Entering Rivus at Pier 2/3, suspended over the waters of Sydney’s harbour, we were greeted by the Torres Strait 8—traditional owners of Bolgnu and Saibai islands who are following Eddie Mabo’s historic High Court Native Title victory for the islands of Miriam Mer: Mabo v. Queensland 1992. The Torres Strait 8 have initiated legal action and will take Australia’s failure to reduce its carbon emissions to the United Nations Human Rights Commission.

Fiona Elisala-Mosby comes from Dauan (between Bolgnu and Saibai), at the top of the Torres Strait Islands, almost touching PNG. Her installation of unique pochoir (stencil) prints, titled ‘Woer Waiz (Water Rising Wall)’ (2020), show the orientalist view of happy feet dipping into blue water. Elisala-Mosby’s sea wall is subtly inlaid with Mineral patterns (classic Melanesian designs). Sea walls will not stop ever-rising water. In 2021, Tuvalu’s Foreign Minister Simon Kofe, memorably made this point when he addressed COP26 in Glasgow standing knee-deep in sea water.

Left: Aliansyah Caniage & Kamila Raisa, Composing Archipelagos Edition, Cards Against History, 2021. Set of 120 playing cards in teak box with metal fittings, off-set printing on velcro-backed cardboard with gold embossing, edition of five, Cards each 21 x 15 cm. Box 34 x 35.5 x 28 cm. Installation dimensions variable. Right: Aliansyah Caniago, Cabinet of Common Beings, 2021. Acrylic, ink and oil pastel on canvas. 600 x 150 cm. Tree branches each 10 x 260 x 10 cm. photo Rémi Chauvin Courtesy the artists and Contemporary Art Tasmania

Writing for her equally ambitious exhibition, Composing Archipelagos (Contemporary Art Tasmania, Hobart, 2021) curator Jasmin Stephens notes that, ‘The archipelago with its unifying but elastic quality asserts the ocean as a connecting rather than a dividing force.’ Aliansayah Caniago’s startingly blue painting ‘Cabinet of Common Beings’ (2021), drawn from Composing Archipelagos, re-connects endangered species and script from pre-colonial trade languages such as Jawi (Arabic/Malay). In contrast, museum cabinets often house de-contextualised wonders as if tossed onshore by legitimate events, not plunder. Museum exhibitions are shifting from complicity to using public spaces as problem-solving agents.

For many years, Sarah Pirrie has walked along Darwin’s inter-tidal zone and transformed her observations into lyrical artworks. Her luminous work titled RISE is an imaginary horizon line inhabited by a cast of characters drawn from mangrove wrack and diffracted by means of a Riso printer. Pirrie shows the contextual relationships of mangroves as salt and fresh waters move through their filtering roots, pulsing and flowing. What is real, what is natural? The artist says, ‘The wrack line of a local beach in Darwin, on Larrakia Country, is a fitting visionary subject of spatial and temporal rising sea levels.’

The most recent of the Reports by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2022) highlights the ‘compounding’ impacts of climate change, and how impacts in one sector can ‘cascade’ into other sectors. Compounding impacts are when multiple events amplify the effects of the other, such as, the combination of more intense cyclones and sea level rise. Many recent exhibitions expand on these themes, from Big Weather at National Gallery of Victoria, which offers a First Peoples view on climate change, to Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes, 2021, and activist archive at Framer Famed, Amsterdam.

The scientists’ reports viscerally chronicle the collective failure to limit global warming to 2 degrees Celsius (preferably 1.5 compared to pre-industrial levels). Most ecosystems are in a perilous position. Over 90 per cent of coral reefs and their ecosystems are collapsing; none is dying more photogenically than the Great Barrier Reef. Other less picturesque dying ecosystems include alpine ash forests, mangroves and marine kelp forests. All have an extremely high carbon storage capacity which grants them high economic importance comparable to rain-forests.

Tita Salina and Irwan Ahmett, BATAM (Bila Anda Tiba Anda Menyesal / When You Arrive You’ll Regret), film, viewing room (centre). Installation view, The Cross Art Projects.

In RISE 2, is the elegant film essay by Tita Salina and Irwan Ahmett, ironically titled ‘BATAM (Bila Anda Tiba Anda Menyesal / When You Arrive You’ll Regret)’ or, simply, ‘Regret’. In this darkly witty artwork, Irwan enacts a Pyrrhic border crossing to ‘escape’ from Batam Island in Riau Archipelago to the glittering future of Singapore. The emissions targets for 2030 set in the Paris Agreement are just eight years away. From remote Torres Strait to mega-cities like Jakarta, enforced climate refugee status continues to increase.

RISE 1 presented a wall graphic written by Sienna Stubbs for the exhibition Big Weather (National Gallery of Victoria, 2020). An excerpt reads: ‘For 60,000 years, we as Yolngu have lived in harmony with the land through our system of gurruṯu, the system that relates everything in the world to each other. Through gurruṯu, everything is connected….’ RISE 2 follows RISE 1, and both are visualised as interconnected exhibitions. In RISE 1 three generations of Yolngu artists illuminated the concept of saltwater estates, using the example of the estate of Rulyapa—part of the ocean between Yirrkala and Dhambaliya (Bremer Island), in North-East Arnhem Land. The artists are fighting to regain Aboriginal custodianship. Siena Stubbs’ essay for Big Weather, ‘The past is in the present is in the future’. Download as pdf

Artists Biographies

Aliansyah Caniago (b. 1987) lives and works in Bandung, Indonesia. He studied Painting at the Bandung Institute of Technology Faculty Art and Design. Aliansyah contributes to regional and international exhibitions and workshops, often with partner Raisa Kamila, to engage with communities and their environmental concerns. Recent exhibitions include: Composing Archipelagos, Contemporary Art Tasmania, 2021. Morning in Gyeongju, Gyeongju Arts Centre, Gyeongju, South Korea (2019); The Tree Without Roots, Taipei Botanical Garden, Taipei, Taiwan (2018). See: https://indoartnow.com/artists/aliansyah

Fitri DK (Fitriani Dwi Kurniasih)

Fitri is a visual artist and writer from Yogyakarta who uses graphic art techniques to encourage dialogue on environmental and social issues, particularly women’s rights. Fitri is a member of SURVIVE! Garage community, Taring Padi art collective, the all-women artist group Bunga-Bunga Besi, and a vocalist in Dendang Kampungan. Taring Padi are major contributors to Lumbung, documenta 15, Kassel, Germany, 2022.

Fiona Elisala-Mosby

Fiona is from Dauan Island in the northern islands of Zenadh Kes (the Torres Strait) and lives and works on Moa Island where she is is Studio Co-ordinator at Moa Arts. Fiona graduated from Queensland College of Art with a Bachelor of Visual Art in Contemporary Australian Indigenous Art and has been exhibiting at art fairs and in galleries since 2015. Her weaving is represented in Long water: fibre stories, a touring exhibition by the Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane. See: https://moaart.com.au/

Narelle Jubelin

Narelle Jubelin’s research-based practice incorporates inter-relations in the histories of imperialism and modernism. Her use of the miniature relates to feminist art and marginalisation, for example the role of women weavers in Timor-Leste’s independence struggle, Elastic / Borracha / Elástico: Dili / Darwin / Sydney (2014). In her installations her artworks are frequently exhibited alongside historically embedded ones. She lives in Madrid with architect Marcos Corrales Lantero, often a collaborator in her exhibitions. See: https://thecommercialgallery.com/artist/narelle-jubelin/biography

Sarah Pirrie

Sarah Pirrie’s work has referenced a range of social and environmental issues and is often shaped by local activity and phenomena in and around Darwin. Her art practice is conceptual, site-responsive and often collaborative. She works as an artist, educator, curator and writer and has exhibited extensively in solo and group gallery exhibitions in Australia since 1995. See: https://sarahpirrie.com/

Tita Salina and Irwan Ahmett

Film work by Ahmett and Salina (as AhmettSalina Studio) is suffused with a self-organised spirit in part owing to the city of Jakarta, a megacity of 15 million people. Their tactical, interventionist work brings into play sharp social commentaries on urgent issues concerning urban development, ecological catastrophes, political repression, colonial legacies, and the exploitation of human and ecological resources. Ahmett and Salina have recently exhibited their works in 10th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art’ (APT10), Brisbane (2021-22), and Contemporary Worlds: Indonesia, National Gallery of Australia (2019), Bangkok Art Biennale, (2020)

Pennyrose Wiggins

Pennyrose Wiggins is an artist, sculptor, designer and New Zealander, now based in Darwin Wiggins traverses the Top End landscape and the symbols unwittingly embedded in road signs. She uses brushwork and detail to create a new meaning. She exhibits with Outstation Gallery, Darwin. See: https://pennyrosewiggins.nz/

Muhammad ‘Ucup’ Yusuf

Ucup’s reduction woodblock prints feature impossibly dense scenes containing pop and traditional cultural references surrounding a central idea. His artistic practice is committed to exposing difficult realities that exist in Indonesian society including corruption, environmental degradation and the continued deprivation of the underclass. Yusuf is a member of the Indonesian arts and culture organisation Taring Padi and is a founder and co-director of the artist project space SURVIVE! Garage community. See: https://survivegarage.wordpress.com/

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss