Nurturing Indonesia: Medicine and Decolonisation in the Dutch East Indies (Cambridge University Press, 2018)

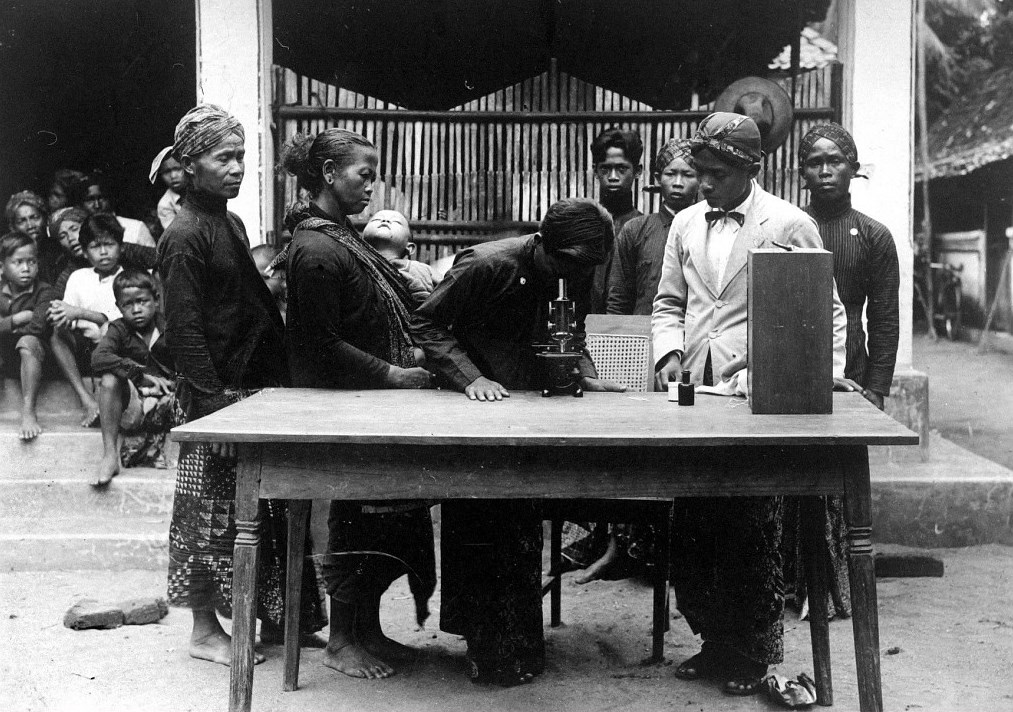

Agus Sugianto, Tulungagung (Artist); Collection Hans Pols

Hans Pols’ (University of Sydney) book offers fresh perspectives on the history of Indonesian nationalism and the sociopolitical role of medicine in the colonial context of the Netherlands East Indies. The book asks a deceptively simple question: why were doctors and medical students such prominent participants in Indonesia’s nationalist movements? Many historians of Indonesian nationalism have observed that physicians and medical students played a leading role in those movements, but few have thoroughly investigated why this might be the case, and how exactly the relationship between nationalism and medicine worked. This is the gap filled by Nurturing Indonesia.

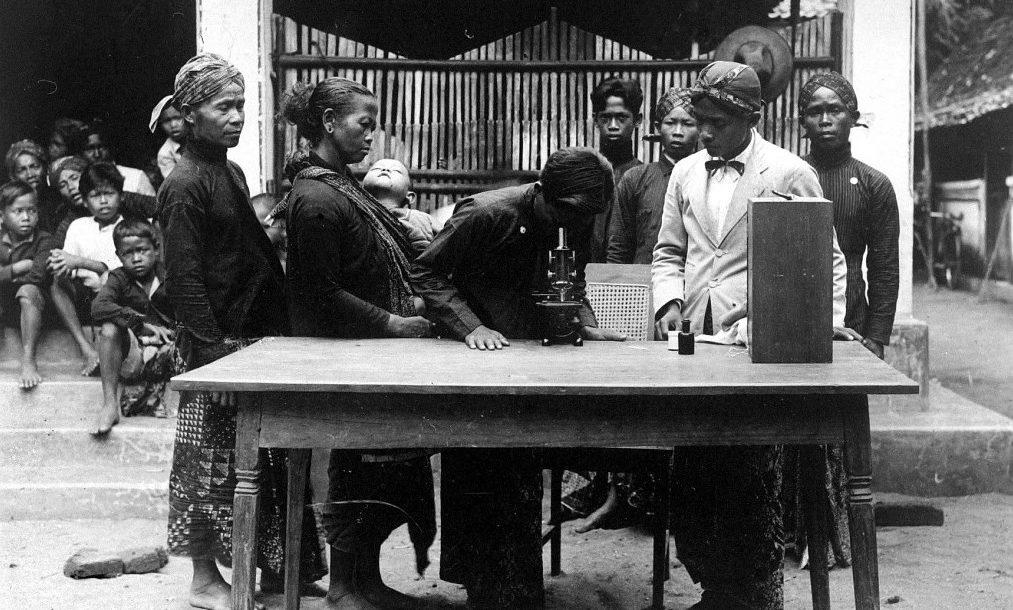

Pols’ argument is that the decision to give the Indies’ indigenous people access to medical training laid the groundwork for anticolonial activism, in three ways. First, the intellectual and social status accorded by medical training caused indigenous doctors and medical students to occupy a unique hybrid position within the strict racial hierarchy of Indies colonial society. Native doctors’ status as equivalent to, but never fully Europeans fuelled personal resentments that translated into bitterness towards the colonial system as a whole.

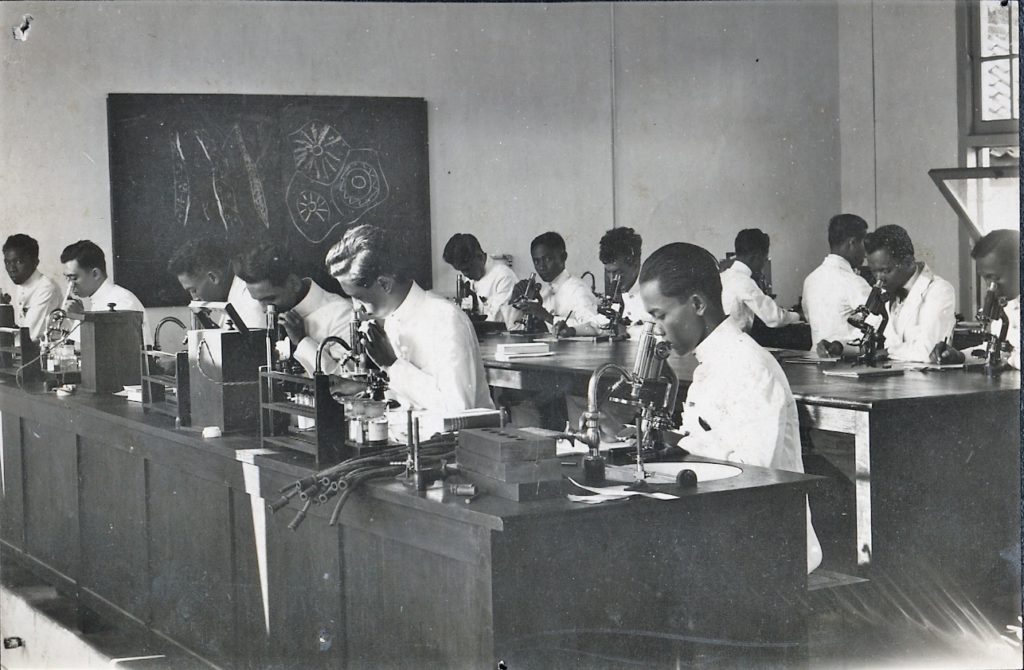

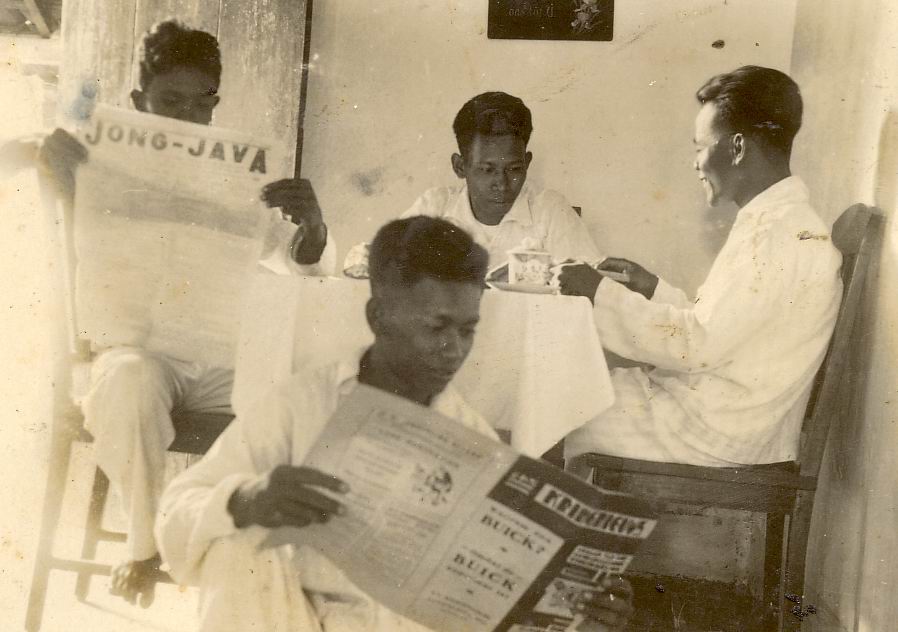

Second, the physical autonomy of the medical boarding schools created a cohort of young people who felt relatively unconstrained by customary and ethnic ties, and therefore defined themselves first and foremost as Indies natives, rather than as Javanese, Minangkabau, etc. This freedom and pan-Indies identity, as well as their facility with the Dutch language, made it easier for medical students and graduates to effectively organise around nationalist and anti-colonial causes.

Third, these students’ knowledge of medicine and biology provided them with a powerful set of rhetorical tools for critiquing colonialism. Through the metaphor of society as an organic body, they were able to pathologise the colonial condition, pointing to concrete instances of injustice and cruelty as symptoms of a systemic disease that needed drastic treatment.

Collection Indropo Agusni, Surabaya

Pols’ approach to this historical argument centres around a collective intellectual biography of the community of doctors and medical students who were politically engaged in the nationalist movements. Rather than a series of cradle-to-grave biographies of individuals, the book offers a structured account of the “ideas, initiatives, and careers” of notable members of this medical community. A particular strength of the book is the clarity with which Pols explains and illustrates the battle of ideas that took place in the early 20th century: the discourse of progressive modernity along Dutch lines that was articulated by the first generation of medical graduates, the backlash by the next generation who rejected this social Darwinism in favour of the ideal of an alternative Eastern modernity, and the reactionary agenda of Dutch and Eurasian psychologists who stereotyped the ‘Eastern mind’ as being essentially primitive.

The three most intriguing chapters of Nurturing Indonesia are: the second chapter, which discusses the development of a medical community through the institution of the native medical schools; the fifth chapter, which discusses the political implications of debates in colonial psychology; and seventh chapter, which deals with the impact of the Japanese occupation on the medical profession and their subsequent political role.

Collection Hans Pols

The second chapter describes the impact of the indigenous medical schools: how they created a community of highly-educated young people whose horizontal ties and mastery of Dutch superseded their class and ethnic identities, thus paving the way for the beginnings of an Indonesian national identity. Pols argues of Boedi Oeteomo, generally considered the Indies’ first nationalist organisation, that its founding “was the outcome of the vibrant intellectual life at the Batavia Medical College” (p. 67). While this chapter is strong on detail, it glosses over the role of women medical students and graduates in this period, offering only hints of women’s presence in these important developments.

The fifth chapter focuses on colonial psychiatry and psychology. Pols shows how reactionary Dutch and Eurasian politicians misused psychological theory in order to argue that the minds of Westerners and Easterners were essentially different, thereby justifying colonial domination as a natural state of affairs. Especially interesting was the argument made by Mohammad Hatta, the future Indonesian prime minister and vice-president: “Hatta’s critique of the damaging psychological effects of colonisation was clearly influenced by the analysis of colonial psychiatry by the physician members of the Perhimpunan Indonesia [Indonesian Association]. This critique formed one of the earliest sustained analyses of the role of psychological and psychiatric theories in colonial society as well as the psychological consequences of colonisation. Thirty years later, these issues would become familiar to a broader public through the writings of Franz Fanon.” (p. 130)

The seventh chapter deals with the Japanese occupation (1942–45), a period that has generally been treated with great ambivalence in Indonesian historiography. Pols identifies three main groups within the medical community, who were distinguished by their different responses to the occupation. The older generation of doctors took advantage of the removal of Dutch leadership by taking control of the healthcare system, without becoming politically committed. Younger medical students tended towards an oppositional stance against the Japanese occupation, which allowed many of them to successfully pursue political opportunities after the war. The third group, represented by the Association of Indies Physicians and the influential doctor Abdul Rasyid, were discredited by their association with the Japanese. The result is the general erasure of this group from national historiography: “Abdul Rasyid has been written out of Indonesian history. External histories rarely mention him.” (p. 181)

Collection Hans Pols

Nurturing Indonesia will have wide appeal, as it is written with clarity and in an engaging style. But it will be especially useful to two groups of readers. Those interested in the history of medicine will find a detailed case study of medicine in a colonial context; one in which indigenous experiences are placed at the centre of the discussion. In contrast to many accounts of colonial medicine that highlight its role as a tool of empire, Pols shows how medical education allowed for the growth of anti-colonial sentiments and nationalist activism. This has implications for general theories of 20th-century nationalism. Readers who are interested specifically in the development of Indonesian nationalism will find a fresh take on the topic. The contributions of well-known figures such as Ki Hajar Dewantoro and Cipto Mangunkusumo are given new meaning by Pols’ analysis of their roles in the indigenous medical community. In contrast to the usual approach of analysing these figures as nationalist individuals, Pols’ study of the medical community and his use of the concept of medical nationalism, offers fruitful leads for further research.

Nurturing Indonesia will be officially launched on Thursday 27 September at the Nicholson Museum in the University of Sydney.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss