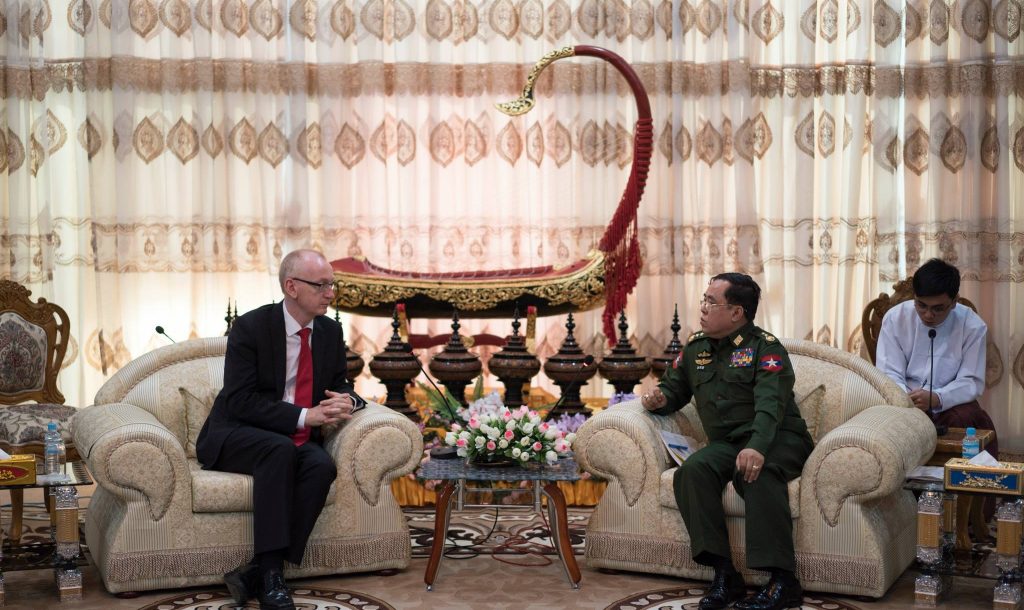

New Mandala co-founder Andrew Walker in conversation with Lt Gen Wai Lwin, the Minster for Defence. Photo: James Walsh

This column was published in The Myanmar Times on Monday, 28 March 2016.

On a recent Tuesday, I turned up, unannounced, at the National Archives building in Naypyitaw. I confess I was not sure what reception my New Mandala collaborator, Andrew Walker, and I would receive.

There was a time, not so long ago, when any “walk-ins” at a government facility would struggle to get a positive reception. The barriers to entry were high. Appropriate paperwork was essential.

Andrew and I had nothing: just our business cards and a modest ambition to learn more about one of the country’s far-flung corners during an obscure period of Myanmar history. We presented these credentials to the first wave of friendly staff and were asked to wait while they reverted to higher authority.

Within minutes, we were being shepherded through to the appropriate reading room, where the archival database – computerised and easy to navigate – was put at our disposal. Andrew, who was the driving force behind this expedition, paid a small fee and got himself registered as a user of the archives, valid for both Naypyitaw and Yangon.

Before we knew it he was loaded up with important research material and encouraged to continue his hunt for obscure files when we returned to Yangon. In the meantime, the archive staff went out of their way to copy a big batch of records that we picked up a day later.

The archive workers were clearly proud of their facilities and the ease with which they could attend to our requests. For researchers, both Myanmar and foreign, this level of access and openness will prove a tremendous advantage in the years to come.

Archives store government records, and so it is not as though there are no sensitivities involved. Anybody who has spent time trawling through archival material appreciates that official business has a habit of reverberating down the generations.

Archival sources are particularly valuable to historians but can also provide great insight for anthropologists, economists, geographers, political scientists, sociologists and more. The search can be painstaking, but it often pays serious dividends. Where digitalisation has occurred, then even the hard work of scouting for sources is greatly simplified.

Other aspects of doing research in Myanmar are also getting much more straightforward. Under the government of President U Thein Sein, it was usually possible to get meetings with officials, big and small. Old hesitations about sitting down to chat with foreign researchers had faded, leaving behind a natural curiosity about the types of questions they would want to ask.

In the early years of the U Thein Sein period I recall being unexpectedly seated next to a retired senior army officer. As we got talking about the life of an academic focused on Myanmar society, he challenged me to ask the questions that the scholarly community struggles to answer.

What followed was an entertaining hour when I put to him some of the big intrigues of the past century. While he admitted he did not know the answers to all the questions, he was genuinely curious about the blind spots in academic knowledge. It was probably one of my most useful research sessions. Ever.

It was also a product of an auspicious confluence of experience, collegiality and access.

Happily, there are now more consistent opportunities for foreign researchers to benefit from these kinds of interactions. Yangon is filling up with a rising generation of analysts and academics eager to get their heads around the opportunities for serious enquiry.

Some are focused on immediate concerns: peace processes, ethnic conflicts, political reform, legal impunity, economic development. Others are committed to studying historical, religious, cultural and social issues. Taken together they represent an unprecedented research engagement with Myanmar affairs. The best of them are building strong new collaborations with Myanmar colleagues.

It helps that many are able to spend long periods in the country; some even have official research permission. One consequence of this better access is that increasing numbers of scholars are developing field sites outside Myanmar’s big cities. Major provincial towns are more accessible than ever for researchers looking to get a different perspective on Myanmar life.

Before long I anticipate that we will see researchers secure permission for long-term, village-level studies of the type that has been so common elsewhere in Southeast Asia. Until now, most of the research of a substantial variety in rural Myanmar has been undertaken either by Myanmar or Japanese scholars.

We are also seeing a new wave of heavy investment in the data gathering that will support long-term economic and political planning. The 2014 census helps in this regard. It has been followed by other surveys that have sought to capture new information about how Myanmar is changing.

It is the nature of academic debate that those who are involved in all of this research activity will come to different conclusions. That is healthy and productive. With mutual respect for different research methods, there should be plenty of opportunities to keep learning from each other.

Nicholas Farrelly is director of the Myanmar Research Centre at the Australian National University and co-founder of New Mandala. His column appears in The Myanmar Times each Monday.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss