This month marks 79 years since the decisive defeat of Allied forces in the Battle of the Java Sea (27 February 1942) and the Battle of the Sunda Strait (28 February – 1 March 1942). These battles were a turning point in the region, representing the beginning of three years of Japanese occupation and the effective end of colonial rule in the Dutch East Indies. Although many decades have passed, the sinking of these vessels, and the catastrophic loss of life that accompanied their destruction, continues to echo today as nations grapple with the complexities arising from the presence of foreign naval shipwrecks in Indonesian territorial waters.

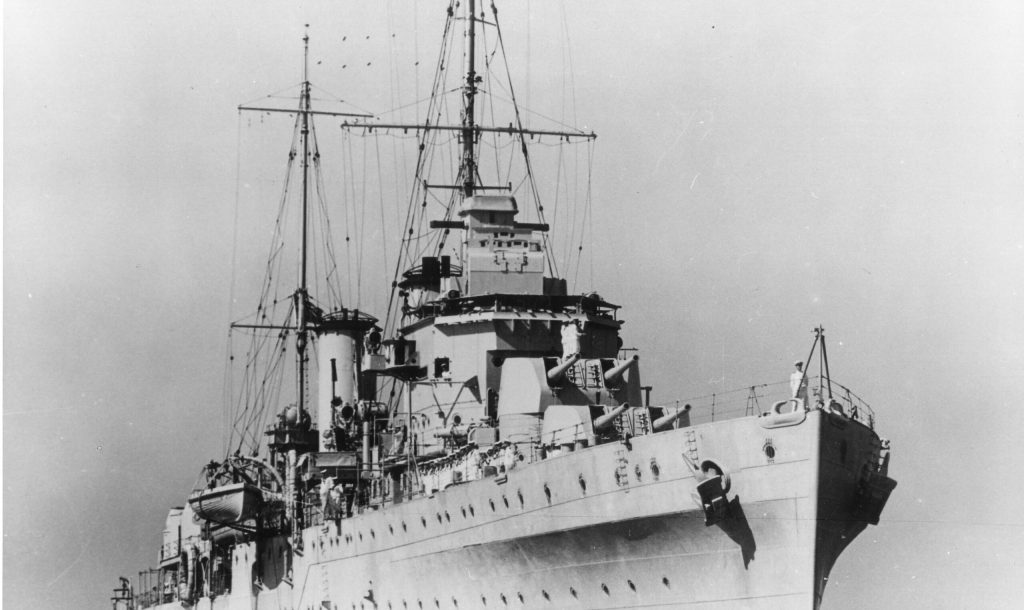

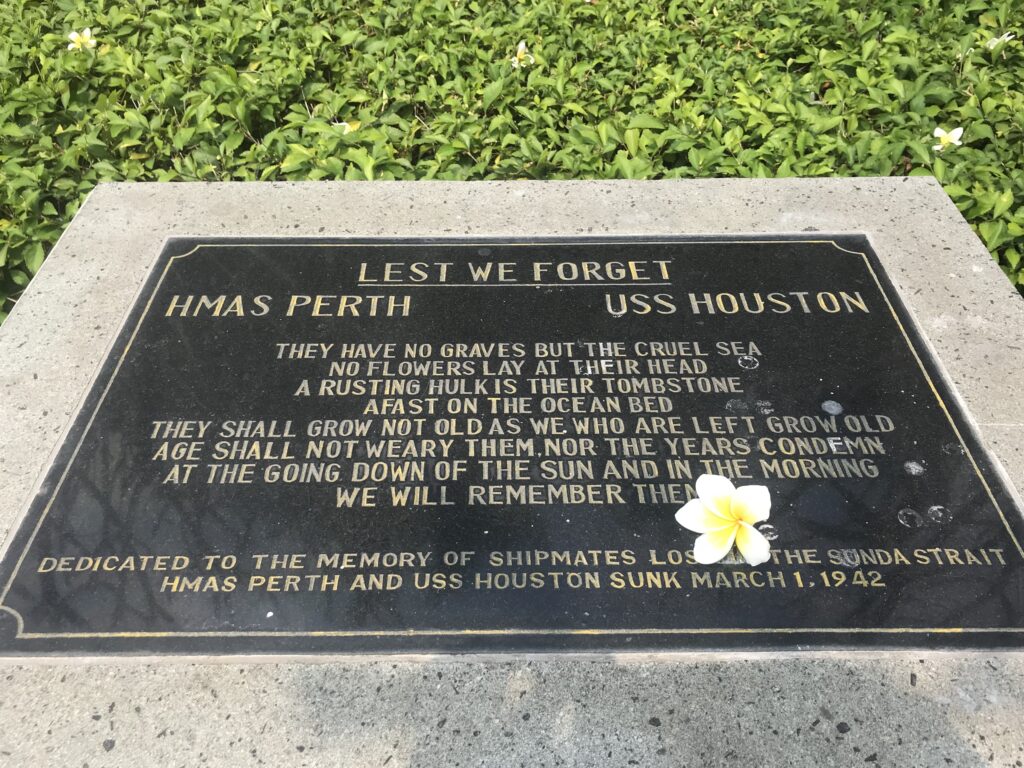

Cooperation and collaboration are essential if this maritime heritage is to be managed for the future. For Australia, the focus of bilateral maritime heritage cooperation has been HMAS Perth (I), a modified Leander class cruiser that lies – together with an American heavy cruiser, USS Houston – in Banten Bay, west of Jakarta. Perth’s company numbered 681 men (and they were all men) at the time of its sinking, 353 of whom perished when the ship was sunk by Japanese torpedoes. Of the 1061 aboard USS Houston, 693 died. Those who survived the Battle of the Sunda Strait were taken as prisoners of war and endured years of suffering on the Thai-Burma railway.

Remembering Perth and Houston at the Australian Embassy, Jakarta. Image credit: Natali Pearson

The wreck of the Perth was rediscovered in 1967 by an intrepid Australian diver, David Burchell. He sought to recover touchstone objects from the vessel before it was ravaged by what he called ‘diving pirates’, who, he feared, were salvaging non-ferrous metal from the many sunken warships scattered across the region. Official support for Burchell fluctuated, and, while the Australian and Indonesian governments did not actually block the project, nor did they show a lot of enthusiasm. After 25 years in the warm waters of Banten Bay, both Perth and Houston had become thriving marine ecosystems, alive with colour. The marine life attracted birds, meaning local fishermen relied on these wrecks for their livelihoods and also as navigational aids. To locate Perth, Burchell drew on the knowledge of these fishermen. His success in locating Perth was rewarded by the Australian Embassy with the gift of four tins of condensed milk . Burchell recovered various objects from the wreck, some of which are on display at the Australian War Memorial. Although Burchell was not successful in locating either Perth’s working bell or its ceremonial bell, he later played a key role in repatriating the working bell after it surfaced at an Indonesian salvage yard in the 1970s.

HMAS Perth (I)’s ceremonial bell, circa 1984, with other salvaged objects. Image credit: David Barnett

Burchell’s efforts, documented in his book The Bells of the Sunda Strait, were the first of many human interactions with the wreck of HMAS Perth (I). Many of these interactions have been motivated by a desire to pay respect to Perth and the sacrifices made by her crew. Some visitors have placed floral wreaths into the water above the site, while others have descended below the waves to the wreck itself. These divers, some of whom visited the site on a semi-regular basis, were the first to sound the alarm in 2013 that Perth was being heavily salvaged. By 2017, a survey conducted by the Australian National Maritime Museum and the National Research Centre for Archaeology (Pusat Penelitian Arkeologi Nasional, or ARKENAS) found that just 40% of the Perth remained in situ. A follow-up survey conducted in 2019 indicated that Perth had also suffered as a result of the December 2018 tsunami in Banten Bay. Meanwhile, the industrial scale-salvaging of Perth was followed, a few years later, by the complete removal of numerous Allied warships in the Java Sea (Fock and Willan 2016). To the distress of survivors and descendants, the presence of human remains on these sites had not deterred the salvagers, who instead prioritised the scrap-metal value of the wrecks.

For Indonesia and Australia, the salvage of Perth has put maritime heritage cooperation into the spotlight, prompting greater bilateral engagement and collaboration in an effort to protect and preserve HMAS Perth (I). The 2017 survey, for example, was used to lobby then-Minister for Marine Affairs and Fisheries, Susi Pudjiastuti, to issue a Ministerial Decree in February 2018 designating HMAS Perth (I) and surrounding waters as Indonesia’s first Maritime Conservation Zone (Kawasan Konservasi Maritim) (Keputusan Menteri Kelautan dan Perikanan No.21/2018). Since then, key stakeholders on both sides have worked hard to develop and refine a comprehensive management plan for the site, whilst also navigating the complexities of the new legislation, which was introduced nationally but must be implemented at the provincial level.

The race to save up to 50 shipwrecks from looters in Southeast Asia

How should we respond when heritage is damaged or destroyed?

While local communities and stakeholders from across different levels of government have been involved in discussions on how to protect and preserve this and other significant shipwrecks in Indonesia, opportunities for Australia to engage with the next generation of Indonesian practitioners and scholars have evaporated due to COVID-related travel restrictions. To address this, a new online course beginning next month will enable Indonesian students to learn more about the challenges and opportunities of managing underwater cultural heritage in an Indonesian context. The course brings together many of the key partners working to support better management outcomes for HMAS Perth (I), including the Sydney Southeast Asia Centre at the University of Sydney , the Australian National Maritime Museum , the Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries and four key Indonesian Universities (Universitas Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa (Serang) , Universitas Indonesia (Jakarta) , Universitas Hasanuddin (Makassar) and Universitas Gadjah Mada (Yogyakarta) . The course is supported by the Australian Government through the Australia-Indonesia Institute of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, and is currently accepting applications .

Scuba diving on the wreck of USAT Liberty, Tulamben, Bali. Image credit: Hence Kertajaya (Royalty-free Shutterstock)

Each year, and as Perth’s condition continues to change, the anniversary of the Battle of the Sunda Strait provides a valuable opportunity to reflect on the significance of the Perth and to consider anew how best to do justice to this wreck and its communities. In doing so, there is a need to broaden the scope of our understanding of underwater cultural heritage management beyond a conflict-centred approach to one that also creates space for multiple viewpoints, including not only survivors and descendants but also those who have lived with the wreck in their waters for close to 80 years. Establishing and nurturing partnerships between Australia and Indonesia is key to achieving this objective.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss