Prior to the 17 April election, the 2019 Indonesian presidential contest was often described as one pitting progressive against extremist Muslim coalitions. Incumbent Joko Widodo (Jokowi) ran on his record, stressing economic development. Challenger Prabowo Subianto presented himself as a religious/economic nationalist. He relied on hate speech demonising Jokowi in efforts to polarise the electorate along religious lines. He tried to convince voters that his opponent is not a true Muslim, and indeed, is an existential threat to Islam and the Muslim community and that he would be the saviour of both Indonesia and Islam.

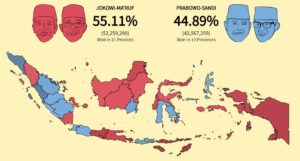

Prabowo’s campaign had many of the features of what Anthony Wallace called revitalisation movements. He spoke in a charismatic, revivalist voice, promising a new Islamic utopia and presented himself as the strong man who would deliver it. He did not succeed. Voters were not convinced and Jokowi won with a comfortable 55% to 45% margin. Regionalism, ethnicity and historical loyalties were the factors driving voting decisions. Support for both candidates was so strongly correlated with ethnicity that it is unlikely that religion was a major factor. Still, a significant, portion of the electorate did find Prabowo’s religious rhetoric convincing. Their potential to influence the future of Indonesian politics is uncertain.

Prabowo, Jokowi and Islam

The great irony of the election was that a deeply religious Muslim (Jokowi) ran on a secularist platform, while his Islamist opponent (Prabowo) had very limited religious credentials. Symbolism, not substance, was at the heart of Prabowo’s Islamist campaign.

Prabowo presented himself as the defender of Islam, but is not especially religious. His level of Islamic education and knowledge is often described as “minimal.” He became a member of Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), Indonesia’s largest Muslim organisation, only in August 2018. Yusril Mahendra, founder of the Islamist Bulan Bintan party, observed that Prabowo does not have a track record for supporting Islamic causes.

Prabowo is from a privileged family with strong ties to the military government of former president Suharto and is from a mixed Christian/Muslim heritage. His father was economist Soemitro Djojohadikusumo who helped to shape Suharto’s developmentalist policies. His mother, Dora Sigar, was an Minahasan Christian from northern Sulawesi. His siblings are Christians. In the fourth presidential debate Prabowo stated: “My mother was a Christian. I was born from the womb of a Christian.” He could have leveraged his religiously blended family background to promote religious tolerance, but chose not to. Prabowo’s Islamist supporters and Christian detractors downplayed his mixed religious heritage. An alim from Bandung told me that he admired Prabowo for being a “strong Muslim” despite his background. An Ambonese pastor said that Prabowo had not learned the “Gospel message” from his mother.

Prabowo is a Muslim and certainly not a Salafi, like many of his supporters. During the campaign, he endorsed prayers for the dead (tahlil) and celebrations of the birth of the Prophet Muhammad (maulid)—both practices deemed heretical by Salafis. In the 1990s he was often mentioned as one of the leaders of the “green” or Islamic military faction. While in the army, he cultivated relations with Kyai (traditional Muslim scholars), not as a source of Islamic knowledge but to acquire supernatural powers some are believed to possess.

Jokowi, on the other hand, is from a middle-class Javanese family in Surakarta. He has deep roots in Javanese culture and maintains strong relationships with NU. His religious mentor is Kyai Abdul Karim of Pesantren Al Quraniy Azzayadiy, a frequent confidante and source of guidance. Pesantren Al Quraniy Azzayadiy has historical ties with Pesantren Tremas. In the early 20th century, Tremas was linked with the most influential ulama in Mecca. Several NU founding fathers studied there. Kyai Karim is a scion of this spiritual lineage. As his student, so is Jokowi. Jokowi understands Islam as “a blessing for all creation.” He rejects movements that “oppress other religions, engage in takfir (condemning Muslims as non-believers), have arrogant mouths and unsheathed swords in their hands, disguise their robbery of other people’s property and cover their bloodstained swords with robes and prayer shawls and use God’s word to deceive people.” These are clear references to Islamist groups that became the core of Prabowo’s campaign.

Historical Loyalties – Soekarno’s Partai Nasional Indonesia (PNI) and Natsir’s Masyumi

A surprising number of people I have spoken with mentioned loyalties dating to the colonial era as reasons for supporting their candidate of choice. Analysis of provincial and local election indicates that history mattered a great deal in the 2019 election.

Indonesia’s first president Soekarno and Mohammad Natsir were two of the giants of Indonesian nationalism and led two opposing major movements whose debates shaped Indonesian politics. Soekarno was fiercely devoted to Indonesian secular nationalism, whereas Natsir promoted an idea of Indonesia as a democratic Islamic state. Soekarno founded Partai Nasional Indonesia (PNI) in 1927. Natsir was Masyumi chairman between 1945 and 1960.

The Democratic Party of Struggle (PDIP) is the successor to PNI. Its leader, Megawati Soekarno Putri, is Soekarno’s daughter. She was also Indonesia’s fifth president. PDIP is a secular nationalist Javanese party. Jokowi has been a member since 2004 when he was elected mayor of Surakarta. Many people in central and east Java are fiercely loyal to Soekarno’s legacy and to Megawati. One man from Purwokerto in Central Java explained that his family has supported the Soekarno family since the 1930s, that he continues this tradition and would follow Megawati anywhere. He supported Jokowi because Megawati did.

Natsir was an ethnic Minangkabau from West Sumatra and a leading Persatuan Islam (PERSIS) intellectual. PERSIS is a modernist organisation rooted in Salafi teachings. Soekarno outlawed Masyumi and jailed Natsir in 1960 for supporting ethnic/Islamic insurgencies. Masyumi followers and their political heirs, never forgave Soekarno and his political heirs. When he was released in 1966 Natsir founded the Saudi-Wahhabi oriented Dewan Dakwah Islamiyah (DDII) that gave rise to many components of Prabowo’s Islamist coalition. PERSIS ulama in Bandung told me that Prabowo is not a religious man, he supported him because Jokowi is PDIP.

Prabowo’s Islamist Coalition

Prabowo’s Islamist image was a product of a pragmatic political calculus. Following a series of high-profile political losses, his thirst for power led him to cultivate an Islamist identity. He founded the Gerindra Party as his personal electoral platform in 2008 with a populist, ultra-nationalist agenda. When that failed, Prabowo ran as an Islamic populist in 2014. For the 2019 election, he relied on an alliance between conservative nationalist and extremist Islamist forces: Gerindra, the Alumi 212/GantiPresiden movement and its “Grand Imam” Habib Rizieq of Front Pembela Islam (FPI). Alumi 212 is the coalition of conservative Sunni traditionalists and Salafis that organised the 2016 AKSI Bela Islam demonstrations leading to the political demise of Jakarta governor Tjahaja Purnama (Ahok), a Christian of Chinese descent, for allegedly insulting Islam. Prabowo’s coalition also included remnants of Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia (HTI) (which seeks to establish a global Caliphate); NU Garis Lurus, a faction that rejects NU’s pluralist positions; and puritanical factions of Muhammadiyah. It was also supported by the Islamic political parties Partai Amanat Nasional (PAN) and Partai Keadilan Sejahtera (PKS).

Jokowi and NU: the view from the pesantren

Islamic boarding schools are ground zero for Jokowi’s efforts to win over the Muslim grassroots. Ideology and patronage are both playing a part.

This coalition is fundamentally unstable because its constituents have incompatible theologies. Salafis are textual literalists. They have an anthropomorphic understanding of God, taking Quranic references to the physical attributes (sifat) of God literally. They consider devotions other than those mentioned in the Qur’an to be sinful innovations (bid’ah). Other Muslims believe that references to God’s physical attributes are metaphors. They believe saint veneration (ziyarah) and prayers for the dead (tahlilan) that Salafis condemn are the sunnah (practice) of the Prophet Muhammad. These have been among the most divisive issues in Indonesian Islam since the emergence of modernist Salafi movements–including Muhammadiyah and Persatuan Islam–in the early 20th century. NU was founded, in part, to counter these developments.

Hate Speech and Campaign Symbolism

Prabowo and his “cyber army” of social media influencers mounted a “black campaign” to persuade voters that Jokowi was an existential threat to Islam and Indonesia. They offered Prabowo as the Muslim alternative to depravity. This is more than normal “dirty politics”. It is the type of hate speech that can lead to communal violence.

Prabowo’s “cyber army” relied on tactics used by Prabowo in his 2014 presidential campaign, and against Ahok in 2017—lies, distortion and innuendo. A series of defamatory claims–each more implausible than the last—were used to denigrate Jokowi and his supporters.

Jokowi is a Communist

Jokowi was depicted as a Communist and a Chinese Christian who planned to sell Indonesia to China. Claims were made that, if re-elected, he planned to eliminate religious instruction in public schools, support same-sex marriage, forbid the sounding of the azan (call to prayer), and prohibit women from wearing jilbab – claims which had no factual bases.

If Jokowi (is re-elected) certainly, the Azan will be forbidden.

He did not “criminalise the ulama (religious scholars)”. This claim was related to pornography charges brought against FPI leader Habib Rizieq that were dropped because the police do not know who uploaded the incriminating evidence. Sources with close ties to the Jakarta police told me that videos disclosed to date are “the tip of the iceberg.”

Stop criminalising our Imam – al Habib Muhammad Rizieq bin Hussein Syihab

Comments on social media described Jokowi as a dog and his supports as dog excrement; a pig, or as one who eats pork; and as being a Syiah Muslim, a Zionist, Chinese, or an American agent. Some suggested that once re-elected, he planned to replace Kyai Ma’aruf with Ahok as vice-president.

Former Muhammadiyah chairman Amien Rais introduced what became a key symbol in this discourse when he referred to Ahok as Dajjal, the anti-Christ who will appear shortly before the Day of Judgement. In 2019, Rais said similar things about Jokowi, announcing that four Dajjal were supporting him. Allegations that Jokowo’s son Gibran Rakabuming Raka used Dajjal symbolism in his café appeared repeatedly in Panjimas and on social media. This type of hate speech establishes social environments conducive to outbreaks of communal violence.

Amien Rais: There is a Political Anti-Christ Behind Jokowi End Times Phenomena

On election day, many voters received a WhatsApp message stating: “If you are a Muslim, number two [Prabowo’s ballot position] is your choice.”

Conversely, the Jokowi campaign stressed economic issues. The campaign homepage did not mention religion. Jokowi highlighted his personal piety to refute Prabowo’s hate speech but did not reply in kind. He performed the Umrah (minor pilgrimage) and was photographed just outside the Ka’bah two days prior to the election. He solicited support from celebrity preachers, including Yusuf Mansur, whose prosperity-oriented message appeals to the urban middle class, and Gus Muwafiq, who is popular among NU millennials. He also garnered support from distinguished ulama including Habib Lutfie and Kyai Maimoen Zubair who blessed his candidacy by presenting him with a sorban (prayer shawl) and tasbih (prayer beads) prior to his pilgrimage.

He stressed endorsements by NU and progressive Muhammadiyah leaders. Many NU leaders despised Prabowo because of his association with Salafis, FPI, and Suharto. They worked quietly in pesantren networks to build support for Jokowi. Anti-FPI sentiments were voiced in Maarif including articles by Muhammadiyah and NU authors. NU activists described their efforts on behalf of Jokowi as jihad. Muslimat, the NU women’s organisation, issued a similar statement. Muhammadiyah does not endorse election candidates and members are free to do so. Former Chairman Syafii Maarif endorsed Jokowi. He expressed concern about Rais’s rhetoric and told me that his old colleague has lost his political acumen and sense of judgement.

Jokowi’s social media campaign was directed by NU activists. It depicted Prabowo as an extremist puppet.

Prabowo as an Islamist Puppet

Provincial and Local Election Results

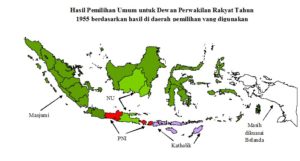

Certainly, some voters found Prabowo’s appeal to Muslim identity politics and demonisation of Jokowi convincing. However, regionalism, ethnicity and deeply rooted loyalties were the election’s deciding factors. The results mirrored those of Indonesia’s first general election held in 1955. In 1955, the Islamic party Masyumi carried predominantly Muslim areas outside Java. Partai Nasional Indonesia (PNI) and NU carried Javanese-majority provinces. PNI and the Roman Catholic Party captured non-Muslim regions. PNI was Soekarno’s party, and, like NU, was primarily Javanese. Masyumi leader Natsir was a Minangkabau from West Sumatra. In 2019, Jokowi carried ethnically-Javanese and non-Muslim provinces by large margins. Prabowo carried Muslim areas outside Java by equally impressive margins. Then, and now, regional and ethnic divisions were at least, if not more, important than religion.

1955 Parliamentary Election Results: At that time NU was a Political Party and there was a Roman Catholic Party

2019 Presidential Election Results

Parallels are equally apparent when provincial results and seemingly anomalous cases are considered. In South Sulawesi, NU and PNI received approximately 20% of the vote in 1955. Masyumi received 42%. The remainder was divided among minor parties. In 2019, Jokowi received 43% and Prabowo 57%. Loyalty to the Masyumi legacy and that of Muhammad Natsir runs deep in the region. The 2014 election in which Jokowi received 71% and Prabowo 20% was an anomaly. Only ethnic factors can explain the difference. Jokowi’s 2014 running mate, Jusuf Kalla, is from South Sulawesi.

Results in Lampung, North Sumatra and Bengkulu further establish the deciding role of ethnicity, religion and history. In North Sumatra, Jokowi received 52% of the vote and Prabowo 48%. The province is approximately 36% Christian which explains Jokowi’s victory. In Lampung, Jokowi totalled 59%. Lampung is more than 50% Javanese. Prabowo won in Bengkulu, by the narrowest of margins, 50.11 %. Bengkulu has historical ties to Soekarno. He was exiled there from 1938 until 1942. His wife Fatimawati, Megawati’s mother, was a Bengkulu native.

Micro-level results also establish the importance of historical patterns. At Yogyakarta Polling Station 18, Prabowo received 78% of the vote. At Polling Station 15, less than a kilometre way, Jokowi received 80%. Polling Station 18 is in the Kauman, a neighbourhood inhabited by pious Muslims that is the birthplace of Muhammadiyah. In the 1950s it was a centre of Masyumi activism. Polling Station 15is near the kraton (palace). This area has been a center of PNI/PDIP activism since 1927. Taken together, this data indicates that religious polarisation was at most a secondary factor in the election. Prabowo’s efforts to incite religious hatred failed. Religious polarisation cannot explain sub-national voting patterns without the untenable assumption that people in the areas Prabowo carried are more inclined than others to find hate speech convincing. A more reasonable conclusion is that they could not tolerate the thought of voting for a Javanese candidate closely tied to Soekarno’s legacy.

The Prabowo Campaign as a Revitalisation Movement: The Politics of Islam and Evil

Prabowo attempted to define the election as a cosmic struggle between Islam and evil. For many of his Islamist supporters, Prabowo’s campaign was a distinctively Javanese revitalisation movement focusing on the imminent arrival of a Ratu Adil or Satria Piningit. Revitalisation movements see society as irreparably broken and irremediably defiled. A charismatic leader appears in the darkest hour, bringing a message of socio-religious reconstruction that followers attempt to establish as social reality. The Ratu Adil is the just king of Javanese prophetic tradition who appears to restore socio-cosmic order in a time of chaos. The Satria Piningit is a divinely inspired cultural/religious hero associated with the Imam Mahdi who will arrive to restore Islam to its pristine condition prior to the day of judgement.

Prabowo has suggested that he is a Ratu Adil since 2014. I have spoken with many Indonesians who described his campaign in this way. By claiming that Jokowi is linked to the anti-Christ and seeks to destroy Islam, Prabowo created a vision of an Indonesia mired in the defiled condition that only a Ratu Adil or Satria Piningit can remedy. The fact that Jokowi carried Javanese majority areas by large margins indicates that appeals to this concept were not convincing to the very audience most likely to find them attractive.

Prabowo was pragmatic in his pursuit of power. He does not seem to take his own rhetoric seriously, though some of his supporters clearly do. On July 13 2019, he greeted Jokowi as a friend. He also had a cordial meeting with Megawati. Many of his most devoted followers were outraged and labelled him a traitor. Alumni 212 declared that they would be loyal only to Habib Rizieq. In October he accepted an appointment as Defence Minister. FPI vowed to distance itself from the tyrannical coalition. Devotees of revitalisation movements rarely abandon hope when “prophecy fails.” The tendency to maintain cognitive continuity leads them to minimise a leader’s failure to meet expectations or to search for one who can.. Many of Prabowo’s followers were willing to abandon him, but not the hateful extremism he proclaimed, after he met with Jokowi and Megawati. Prabowo described their differences as “normal” and vowed to work with them. It is unlikely that those who now call Prabowo a traitor will join with him in cooperating with people they think are evil incarnate. It is impossible to predict what course they will take. This much is clear. Divisions along ethnic and religious lines can be negotiated; however, when an election is framed as a struggle against absolute evil, there can be no compromise or retreat. Ardent supporters of the anti-Jokowi black campaign may repackage their message for the 2024 election if a suitable “Ratu Adil” style candidate emerges. It is also possible that they will resort to tactics other than electoral politics and nearly certain that they will not give up the fight. No matter what strategy they choose, this group’s ability to influence Indonesian politics will depend on the emergence of the type of charismatic leadership that revitalisation movements crystallise around.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss