The Shan rebellion, which broke out in northern Siam in 1902, was an important moment in the formation of the modern Siamese state. The repression of the rebellion witnessed the first large-scale operation of the modern Siamese army in the northern provinces. And, in heightening the bureaucratic anxieties of officials in Bangkok, the rebellion hastened the development of modern administrative structures and the displacement of traditional authorities. Some have also argued that the rebellion had an important impact on the shape of Thailand’s economic development – encouraging state investment in railways (to facilitate the rapid movement of troops) rather than agricultural infrastructure.

An under-explored aspect of the rebellion is the implications it had for for regional geopolitics, particularly the ongoing manoeuvrings between the Siamese, French and British on the upper-Mekong border. Recently, I have been working on French colonial documents dealing with the Shan rebellion. One particular set of documents has caught my interest.

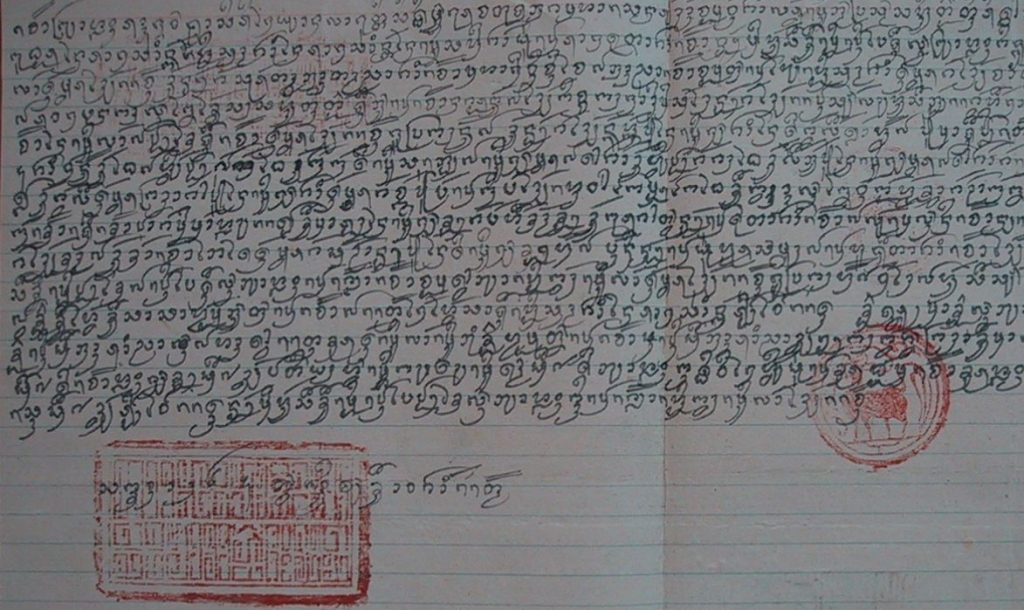

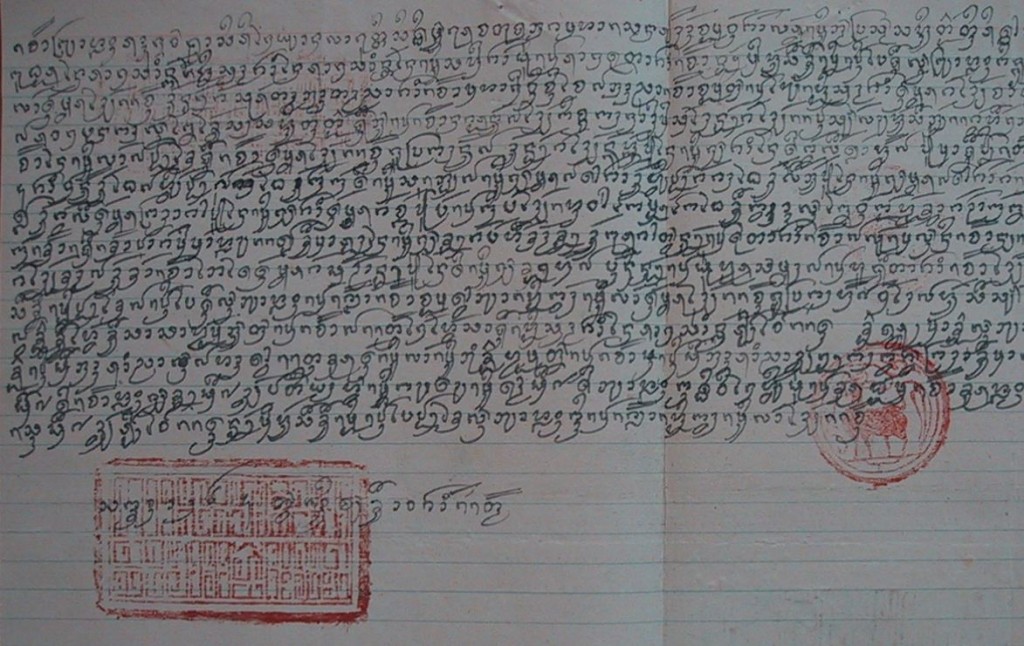

In December 1902 a package of letters was seized by French officials in the far north of Laos (near Luang Nam Tha, I think). The letters were sent to various chiefs in Sipsongpanna, by a Phaya Lassavong who was temporarily based in a village across the Mekong from the town of Chiang Khong. Phaya Lassavong was a “mandarin of Sipgonspanna” who had travelled to Siam and seems to have been involved in the early stages of the Shan rebellion. By September 1902 (along with a many other retreating Shan) he had arrived in the vicinity of Chiang Khong. The captured letters, written in October and November, were addressed to the king of Chiang Rung (Jinghong) and to the chiefs of various other towns in Sipsongpanna.

Lassavong informed the notables in Sipsonpanna about the revolt of the Shan, the oppression of the Siamese, and the retreat of the Shan to Chiang Khong and to French territory on the left bank of the Mekong. He foreshadows a new attack by the Shan in January 1903 and implores the king of Chiang Rung, and the many lesser chiefs, to send 500 troops to help fight the Siamese. Optimistically he suggests that they will be fighting alongside the French in their battle with the Siamese. He also says that the troops will enable him to bring many Lu families back to Sipsongpanna.

Alarmed by the diplomatic and security implications of the letters, the French moved quickly to arrest Lassavong. After some unsuccessful night-time raids, he was eventually captured, along with his son, after a short skirmish with guns and sabres The prisoners were taken to Muang Sing. Lassavong’s son was alleged to be a “most dangerous bandit.” There were reports that he had murdered the son of the chief of Nan, and stolen a valuable ring after cutting the finger that bore it off his body.

French authorities in Muang Sing took action to prevent the incursion of any “armed gangs” across the border from Sipsongpanna. Lassavong was forced to write a letter to his northern allies, stating that if any attempt was made to rescue him, both he and his son would be executed immediately. Plans were made to put him on trial before the royal court of Muang Sing and to send his son back to Nan to be handed over to Siamese authorities.

I am still trying to find out what ultimately happened to them.

I have copies of the letters written by Phaya Lassavong (one of them is in the image above). If there is anyone willing and able to translate them for me, I would be delighted to hear from you!

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss