The scale of the so-called Aksi Bela Islam 212 (Action to Defend Islam 212) mass mobilisation on 2 December 2016 caught many people by surprise, and played a major role in the electoral defeat of Jakarta’s then-popular incumbent governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (Ahok) and his eventual imprisonment over a blasphemy charge. The exact size of the demonstration itself is contested—its proponents claim extraordinary numbers, as high as 7.5 million participants, whereas more sober analysts estimated turnout at somewhere south of a million. But what most people can agree on is that it was and still is the single largest street-level mass mobilisation Indonesia has ever seen.

“Alumni” of the 212 demonstration, pictured at the “Aksi Bela Islam 313” on 31 March 2017

“Aksi Bela Islam 313”, 31 March 2017

A coffee seller cycling past a wreath from PKS cadres for the 212 reunion

Understandably, then, the organisers of the “212” mobilisation (dua-satu-dua, as it’s typically known in Indonesia) were not going to let its one year anniversary go uncommemorated. Indeed, it’s clear from the build-up that they considered the Reuni Akbar Alumni 212 (Great Reunion of 212 Alumni), held in Jakarta on 2 December 2017, to be another historic event in itself. To those with the ambition of using their involvements in the Aksi Bela Islam to advance themselves, the success of the 212 Reunion was critical. This is especially the case in light of the fact that none of the subsequent Aksi Bela Islam mobilisations—in February and March 2017—were able to replicate the scale close to the original 212.

To the typical person who either attended 212 and/or is sympathetic towards any number of the issues (both symbolic and political) under the Aksi Bela Islam rubric, the 212 reunion serves as a commemoration of an important chapter in the “awakening of Islam” in Indonesia; a chapter that many take pride in being a part of and, to extend the metaphor, would like to see develop into a full-length book. The fact that in 2017 the date coincided with Maulid 1439H (the birthday of Muhammad) was seen as a sign of a greater power at play—not to mention the additional Maulid crowd the event could draw.

Alumni from Bekasi putting up their banner.

At the same time, the build-up to the reunion itself was marked by doubts and criticism. Unsurprisingly, much of this came from the generally more pro-government/pro-Jokowi side of the political spectrum. Although the country’s largest Islamic mass organisation Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) did not formally endorse or discourage attendance at the reunion, many NU figures did not hide their lack of enthusiasm over the issue. Ma’ruf Amin—the Rais ‘Aam (chief spiritual advisor) of NU, Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) chairman, and a noted Islamic scholar who led the Friday Prayer at the original 212—questioned the motivation behind the reunion. Referring to the blasphemy charge against Ahok, Ma’ruf argued that the “problem” which caused 212 had already been resolved and there was no need for another mobilisation.

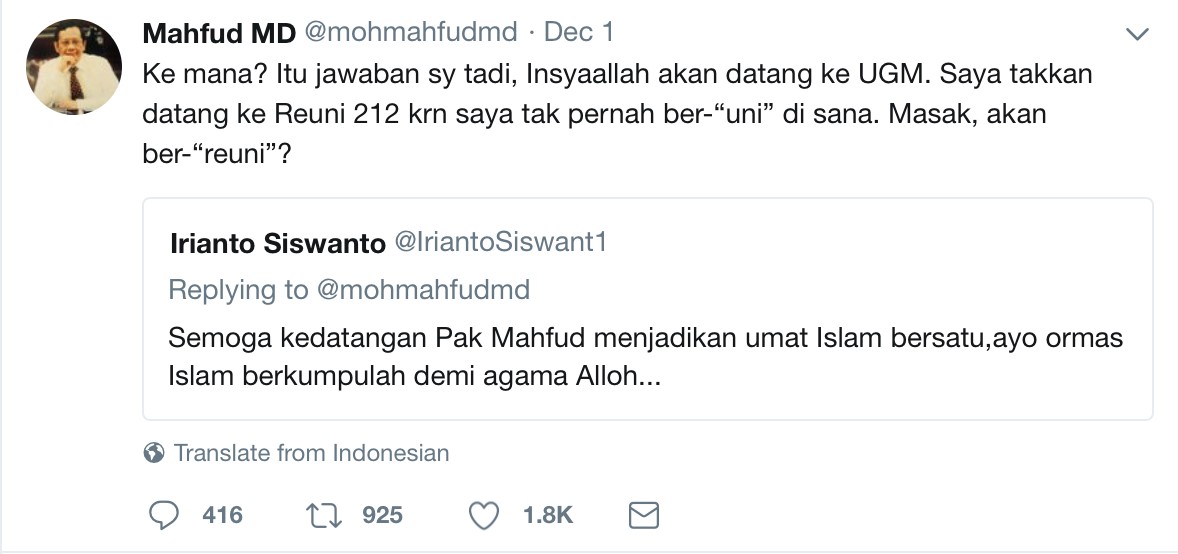

Mahfud MD’s tweet on 212 reunion.

Another heavyweight from an NU background, former Constitutional Court chief justice Mahfud MD, dismissed a rumour that he would attend the reunion. He tweeted that he had never “universitied” there, so why would he be joining its reunion? The Minister for Religion Lukman Hakim Saifuddin also asked that the event organisers to clarify their motivations. Similarly, the Chairman of Muhammadiyah, Haedar Nashir, made a public statement that the country’s second largest Islamic mass organisation had no intention of joining or supporting the demonstration. “It’s better that we only participate at the 17/8/1945 reunion”, he joked, referring to Indonesia’s Independence Day.

On 2 December 2017, it became clear that while the 212 Reunion achieved a scale of mobilisation that hadn’t been seen since the “Aksi Bela Islam 112” held on 11 February, it paled in comparison to the original 212. Analysts have attributed this to the electoral defeat and the imprisonment of Ahok, arguing that the raison d’etre of the mobilisation no longer exists. Judging from the turnout of the 212 reunion and the array of different interests present there, this may well be the case. This does not suggest that the Aksi can be described as being primarily a tool for competing oligarchs. Notwithstanding the politics at the elite level, it’s important to remember that people who attend the Aksi Bela Islam events don’t necessarily share the political objectives of the elites who are supposedly pulling the strings. Similarly, it’s also important to look beyond the rhetoric broadcast from the sound system of the mobil komando (light trucks with an elevated platform and a sound system, commonly used at street demonstrations in Indonesia) and take account of the heterogeneity of people who call themselves the “alumni” of the Aksi Bela Islam.

With that in mind, and aided by the medium of photography, I use this post to reflect on some of the highlights I observed at the 212 reunion.

Dawn prayer at the 212 reunion

“I regret not attending the previous 212. It was such a missed opportunity. When I heard that there’s going to be a reunion, I knew I had to come. I took the train from Bogor at around 9PM the night before, and by the time I arrived at the National Monument, it was nearly 3AM. Thanks to the water trucks provided by the volunteers, I was able to carry out my ablution without much problem. I quickly found a spot and got ready for one of the most best religious experiences I’ve had, conducting dawn prayer with a congregation of hundreds of thousands of people at the National Monument.”

So a friend told me while the leader-in-exile of the Islamic Defenders Front (FPI) Habib Rizieq Shihab took his time to explain his idea of NKRI Bersyariah through a livestream from Saudi Arabia. I found myself struggling to listen to my friend while trying to pay attention to Habib Rizieq’s argument for what he called the authentic constitution based on the Jakarta Charter.

“I’m so tired and I have to rush back to Bogor to go see Justice League with my friends, but it’s worth it. I felt so fresh after the prayer. I’ve never experienced an atmosphere so profound. We were crying, praying for the Rohingya and for Palestine.”

I said goodbye soon after, as my friend rushed to catch a train for his superhero movie, while I stayed behind to wait for another speech from one of the many people competing to speak on behalf of the Aksi Bela Islam.

Young FPI members arriving en masse in the early hours of 2 December 2017.

At around midnightI arrived at Jalan Sabang in central Jakarta, a popular area for night time snacking not far away from the National Monument. I was hoping to catch some of the reunion crowd there. I did, albeit in small numbers. There were some cars bearing various Islamic calligraphy stickers, or stick figures depicting an ideal Muslim family on the rear windows. I ran into a group of people wearing jackets with an embroidered patch of Indonesia’s red-and-white flag on the left and a black ar-Raya Islamic flag on the right, waiting for their Frappuccinos. But the Sabang and Sarinah zone was still largely dominated by Friday night joy seekers. Less than 2 kilometres away from the pious anniversary event of Indonesia’s largest street mobilisation, the weekend hedonism went on unaffected.

FPI member directing traffic.

At around 2am, I decided to head back to the Istiqlal Mosque and the Gambir train station area once I noticed the heavier-than-usual traffic flow. During this time, most of the people arriving were members of FPI’s paramilitary wing, primarily teenagers led by a few more senior members in their 20s, arriving by the truckload.

Volunteers at one of the tents (posko) which provided free drinks

People carrying out ablutions before the dawn prayer

By around 2:30am Jalan Medan Merdeka Selatan, the major road on the southern side of the National Monument home to the US Embassy and the City Hall, began its transition into a makeshift parking space for the participants of the reunion. Most of the vehicles I saw were from Jakarta, which is noteworthy given the widely-held assumption that many of the attendees of 2016’s massive rallies were bussed in from other regions. There were many temporary tents set up by volunteers from different groups, offering snacks, coffee, and medical attention, all without charge.

A long queue in front of the toilet

A young participant.

A few days beforehand, a friend of mine had emphasised to me that the reunion is not a demonstration. “There’s already no protest agenda this time. This is a reunion. It’s more like a symbol of unity of the Islamic ummah of Indonesia.”

The previous night, she had expressed her interest in attending the reunion because she thought it would be a fun and boisterous event. Indeed, most of the people I met there were more in a mood for festivity than protest. People asked me to take photographs for them or with them. When facing the front element of my lens, nearly everyone laughed and posed for the photos.

A participant poses for a photograph.

The festivity became even more pronounced during the breaks between the major speeches, during which time slots were given to the celebration of the Prophet’s birthday. There was some pushing and shoving in the area right in front of the main stage where I spent most of my time after the dawn prayer. But it was just people jostling to get a better view of their favourite preachers leading the sholawat.

Prayers at dawn.

Sunrise over the National Monument.

It’s clear that parallel to the elite-level political intrigues runs a current of pride and joy in being a part of the symbolic awakening of Islam in Indonesia. The Aksi Bela Islam is an opportunity for a symbolic convergence of heterogeneous groups in the name of Islamic unity. The fact that the opportunity was created by inter-oligarchic rivalry does not mean that such a rivalry is how most of the participants and sympathisers experience and make sense of their movement. To people who are outside of the immediate circles of power, one of the most obvious outcomes of the Aksi can be seen in the symbolic unity and show of strength it engenders. Groups which are typically at each other’s throats are now speaking from the same mobil komando and sharing the same increasingly crowded stage (at one point some people were asked to leave the stage due to concern that it may collapse).

A participant praying silently.

While the language of the movement is far from coherent at this stage, and while its leaders and supporters are still struggling to formulate a new raison d’etre, the desire for unity and a symbolic awakening is in the air. What exactly such an awakening means depends on who you speak to. But pondering such a deep question is not what drew people to the reunion in the first place. The awakening was accepted and celebrated as a given—and evidenced by Ahok’s defeat and imprisonment. For the most part, the focus was primarily on experiencing and celebrating a collective struggle for Islamic piety and identity.

Participants shared stories on their social media pages about how early they got up to get to the National Monument. Teenage girls posted boomerang videos of themselves on their Instagram pages wearing ar-Raya flags around their headscarves. People were eager to record what was happening via their Instagram stories whenever possible. These narratives about dedicating oneself to Islamic piety and unity were experienced, digitalised, and memorialised through social media to be relived again on another day. News reports were full of stories about people overcoming difficulties to participate at the reunion—something of a major theme since the beginning of the Aksi’s history. Even on the stage, Jakarta Governor Anies Baswedan was invited to present flowers to the 212 alumni with physical disabilities who made the effort to participate at the reunion.

Anies presenting a flower to the representative of the 212 alumni with physical disabilities.

Another piety-focused theme can be seen when Muhammad Al Khaththath, the Secretary-General of Forum Umat Islam (FUI) and a leading Aksi Bela Islam figure, led a pledge to conduct congregational prayer (salat berjemaah) for every dawn prayer from then on. A friend admitted that he’s pessimistic about the prospect of this “Gerakan Indonesia Salat Subuh Berjemaah”, or Indonesian Movement for Congregational Dawn Prayer. “But it’s still a positive outcome of today. This is what we dedicate ourselves to keep the momentum of Aksi Bela Islam alive for,” he said.

Anies delivering his speech.

A participant waving his ar-Raya flag.

This is not to say that the effect of the divisive gubernatorial election couldn’t be felt at the reunion. Anies opened his speech by celebrating the fact that the National Monument could once again be used for religious events. This was not allowed during Ahok’s administration, which caused a considerable animosity towards the former governor, particularly from the Majelis Taklim (religious study) groups which used to use the National Monument for their events. This caused an uproar of cheers mixed with shouts of “gubernur pribumi!” (“an indigenous [i.e. non-Chinese] governor!”).

For every ten friendly interactions I had at the reunion, there would be one marked by sectarian slurs thanks to my ethnic Chinese appearance. Since I began to attend the Aksi Bela Islam events, I’ve had my fair share of awkward experiences of being on the receiving end of apologies by people I’ve met at the Aksi, delivered on behalf of those who called me names.

Santri from Ciamis.

More 212 reunion participants arriving at the nearby train station.

A wave of new arrivals at the reunion after the dawn prayer.

In truth, I did feel a bit uneasy when people were chanting various “anti-foreign” and “anti-Chinese” catchphrases—especially given that I was probably the only obviously Chinese-looking person right at the stage area (apart, perhaps, from Ustadz Felix Siauw). At some point, a group of people pointed at me angrily while shouting aseng -aseng or cina-cina—derogatory terms for ethnic Chinese. I turned and walked away, only to be greeted by a friendly middle aged man wearing a Palestinian flag around his neck. This man, dressed like a typical member of FPI’s paramilitary wing, wanted to take a selfie with me.

The ustadz leading the prayer broke into tears. Some participants followed suit.

There is no denying that many, if not most, of the 212 alumni uphold interpretations of Islam which in part lead to an exclusionary attitude towards people who fall outside of their pan-Islamic kinship. It is also hard to refute that some of these interpretations come into conflict with the brand of nationalism promoted by Jokowi’s government. Whatever his motives in attending the reunion, Anies Baswedan lent legitimacy to the people he shared the same stage with by doing so. While it may be argued that it’s perfectly legitimate for Anies to endorse Al Khaththath’s aspirational dawn prayer pledge, the space of legitimacy quickly diminished when Anies described Ustadz Sobri Lubis, a firebrand preacher who’d publicly incited violence against religious minorities, as an honourable guest.

People trying to get to the reunion stuck in traffic.

It is therefore understandable that a common response from those who are concerned about the Aksi Bela Islam, and the perceived rise of Islamic conservatism, is to highlight the sectarian, anti-pluralism, and anti-secular undercurrents that can be observed in the movement.

However, to describe the proponents of the Aksi Bela Islam in value-laden terms (such as unpatriotic, intolerant, or racist) on the basis of the movement’s diverse range of self-proclaimed leaders and their rhetoric is both counter-productive and analytically problematic. It brushes over the heterogeneity which exists both at the leadership level and at the grassroots level of the movement. Worse still, such depictions deprive the movement’s participants and sympathisers the sincerity they experience and the authenticity they claim.

There are many legitimate concerns over the mainstreaming of the more exclusivist Islamic teachings in Indonesian society. But calling people who believe in and live by such perspectives as unpatriotic and racist, or resorting to ultra-nationalism to counter their rise, is hardly a productive way to begin what is a much-needed conversation.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss