Indonesia’s General Election Commission (Komisi Pemilihan Umum, or KPU) recently announced the interim list of candidates for the national and regional legislative elections scheduled for February 2024. This list, known as the Daftar Calon Sementara or DCS, provides voters with initial information about candidates’ backgrounds and affiliations. One thing that has caught the public’s attention is the continued trend of retired Indonesian military (TNI) and police (Polri) officers—or the so-called purnawirawan—mounting legislative candidacies.

In spite of having given up their official powers, retired TNI/Polri officers often hold important, if not strategic, positions within Indonesian society, as board members of corporate entities or high-level appointments in state institutions. Meanwhile, there is a tendency from political parties to consider former territorial commanders, notably from the army (TNI AD), as election campaigners or “vote-gatherers”.

Mapping the Indonesian political spectrum

A new survey shows that political parties are divided only by their attitudes on Islam.

To what extent are these factors apparent in the 2024 legislative elections? Using a new dataset drawn from the KPU’s interim candidate list, our analysis shows that at least 69 retired TNI and Polri officers are set to stand for the national legislature (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat, or DPR) in the elections scheduled for 14 February 2024.

Our examination of these purnawirawan politicians’ characteristics and backgrounds suggests that political parties’ needs to recruit “vote gatherers” has driven Indonesian political parties to nominate retired military and police officers as DPR candidates.

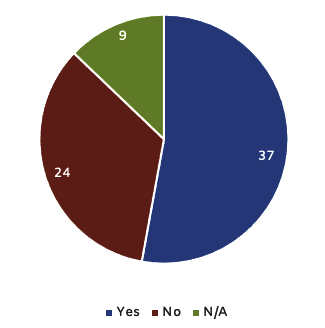

A majority of them have territorial command backgrounds, meaning they were once appointed as a commander in either provincial, city, or district military or police command (see Figure 1 below).

FIGURE 1: Territorial Command Experience of Retired TNI/Polri Officers in 2024 National Legislative Elections

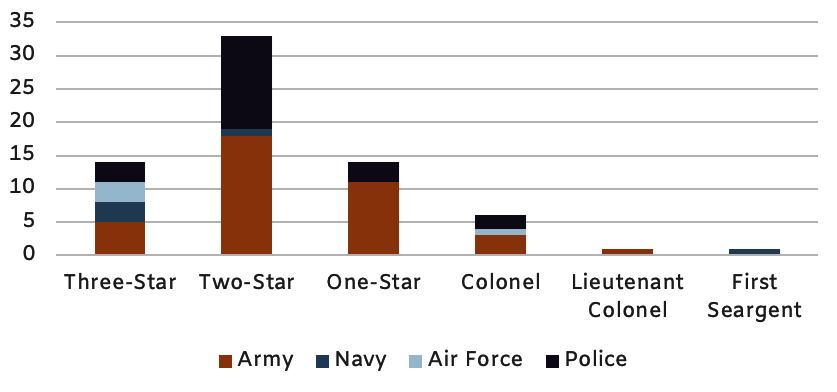

Our study finds that retirees with army backgrounds are more likely to be DPR candidates compared with other services (the navy and air force) and the police. The army is the largest standing force in Indonesia and has fifteen Regional Military Commands (Komando Daerah Militer, or Kodam) all over the archipelago, while the navy and air force respectively only have three regional commands (see Figure 2 below).

FIGURE 2: Rank of Retired TNI/Polri National Legislative Candidates

Furthermore, a big proportion of the nominated retirees hold two-star general rank: there are 18 army major generals (mayjen) and 14 police inspector generals (irjen). Meanwhile, one-star army general (brigjen) comes in third place (11 candidates). The lowest ranked candidate from a military background is a retired first sergeant from the navy.

Retired officers as “vote gatherers”

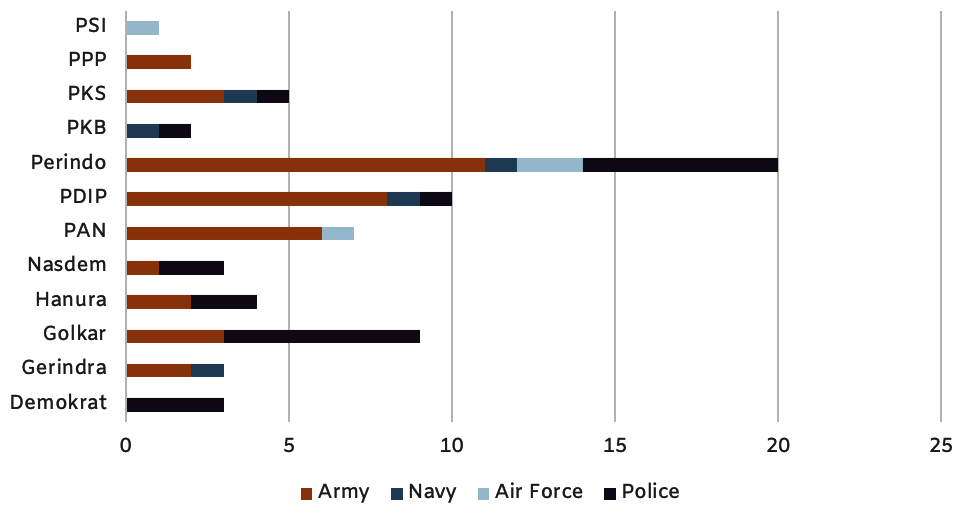

Ahead of the 2024 election the Perindo Party, which did not win any seats in at the previous elections in 2019, has nominated at least 20 retired military/police officers. The winner of the 2019 polls, PDI-P, designated 10 purnawirawan candidates, followed by Golkar party with 9 candidates (see Figure 3). A recent survey by Kompas showed Perindo so far has been the best performer amongst the parties not currently represented in the DPR, with 3.4% electability.

Perindo put 15 out of its 20 TNI/Polri retiree candidates in the top three positions on the part list in their respective electoral districts (dapil). It should be noted that under the open-list proportional representation election system, a candidate’s ranking on the party list has no guaranteed impact on their electability. However, Perindo’s move to rank TNI/Polri retirees high on candidate lists showcases its intention to attract voters with their presence. It is no secret that political parties often assign popular candidates and senior party members to these pole positions.

FIGURE 3: Retired TNI/Polri National Legislative Candidates by Political Party

Other parties have also pursued the same strategy, though the number of retired military/police candidates is lower than in Perindo. In total, 43 out of 69 retired officer candidates are listed in the top three of the party list in their respective electoral districts. Here we can see that political parties are attempting to exploit those retirees’ military and police credentials to gather votes.

To attract voters, it is also not unusual for political parties in Indonesia to nominate putra daerah (“native sons”)—those who have an ethnic affiliation with a majority of the population within the respective electoral district—as their legislative candidates. Our study finds that 24 of the retired TNI/Polri candidates are nominated within an electoral district that contains their hometown. Though this practice is small in percentage terms (34.7%), nearly half of the nominated retirees from Perindo, PDI-P, and PAN are putra daerah. There is also a belief that these putra daerah have advantages compared to outsiders or pendatang. Thus, we can conclude that political parties also consider that purnawirawan’s social-cultural background can help generate votes for them.

In conclusion, the participation of the retired military/officers does not merely revolve around the protection of their own interests and the extension of professionalism as some of the above cited literature has suggested. The need to boost electability made political party leaders to act pragmatically by taking advantage of the popularity and credentials of retired officers. Although it is possible that some of these retired military and police candidates run in the legislative elections to fulfil their own interests, we should not dismiss the role of civilian politicians in dragging those purnawirawan into the legislative election battleground.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss