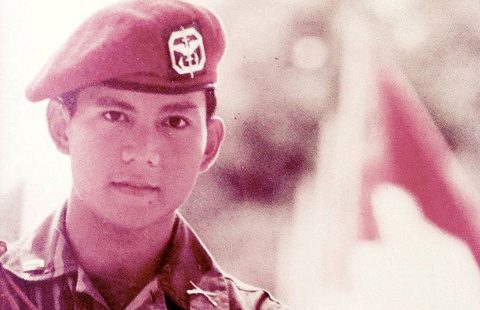

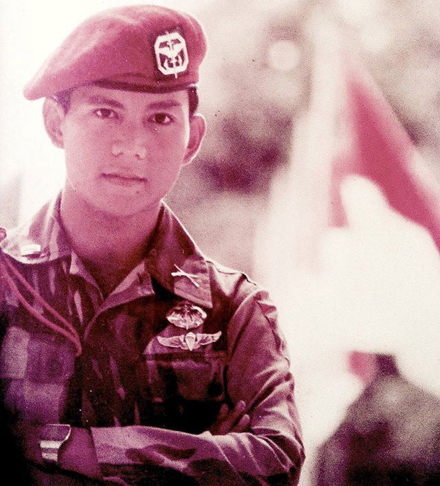

Prabowo Subianto’s time as an exile, has helped him sell nationalism at home and his image abroad, writes Danau Tanu.

In a recent post, New Mandala’s Liam Gammon said of Prabowo:

The pro-business cosmopolitan who can ‘knock Indonesia together’ is the one who shows up to events at posh Jakarta hotels with diplomats and investors. The fist-shaking demagogue is the one who appears in front of the voters. It’s important that foreigners tempted to see Prabowo as the leader Indonesia needs, understand just how different these two personas are.

So, how does Prabowo pull off these personas?

Prabowo Subianto is a ‘Third Culture Kid’. Despite sounding child-like, the term is popular among globe trotters and often appears in the international media. ‘Third Culture Kids’, or ‘TCKs’ for short, describe those who spend their childhood moving internationally multiple times and attend international schools. Prabowo did both.

In the 1950s and 60s, Prabowo left Indonesia and lived overseas with his family while his father was in exile for supporting a failed regional revolt. During this time, Prabowo grew up in Singapore (while it was still under British rule), Hong Kong, Malaysia, Switzerland and the United Kingdom while attending British, American and international schools. Prabowo graduated high school from the American School in London in 1969.

Growing up in six countries as Prabowo did is typical of Third Culture Kids, but it is no easy feat. TCK experts, David Pollock and Ruth Van Reken, explain that, ‘With one plane ride a TCK’s whole world can die.’ These children have to trade in their social network of relationships for new ones each time they move, with repercussions on their adolescent development.

When this is coupled with the reality of having to adjust to a new country, new language and new culture every two to three years, growing up can be rather confusing. It is an elite form of cultural displacement. Unsurprisingly, many TCKs become ‘cultural chameleons’ as a matter of survival. They learn to pick up the cultural cues, languages, accents and mannerisms of their surroundings so as to blend in with the dominant culture.

In Prabowo’s case, he was also a minority within a minority in the majority-white international schools that he attended. In an interview with the tabloid ‘The Politic’, Prabowo explains that he was almost always the only non-white student in class, making it even more important for him to learn to act appropriately within a Western milieu. If there were other non-white students in the school, they were often his own siblings.

Given the immediate post-colonial atmosphere of the time, one of Prabowo’s strongest memory of his experience abroad is that of racism:

There was still a strong sense of superiority among white people, westerners. They often insulted me at school. I was always part of the minority…Because we were often bullied, often insulted, we became tough. I can’t forget the first day I went to school in Switzerland. It was an international school where the majority were Americans. I must have been fourteen at the time. I got on the bus – immediately I was asked, ‘Where are you from?’ I answered, ‘I’m from Indonesia.’ [They said,] ‘Oh, your people still live on trees?’ Can you imagine? It was only the first day and already I was being greeted like that.

Rasa superioritas daripada bangsa kulit putih itu sangat tinggi, bangsa barat. Jadi di sekolah saya sering dihina. Saya selalu kelompok minoritas…Iya, karena kita kan sering diejek, sering dihina jadi kita makin…lebih tough. Saya gak bisa lupa, saya ingat hari pertama saya masuk sekolah di Swiss. Sekolahnya sekolah internasional, sebagian besar orang Amerika. Saya umurnya berapa waktu itu, 14 tahun. Naik bus, langsung ditanya, ‘Where are you from?’ Kamu darimana? Saya jawab, ‘I’m from Indonesia’, ‘Saya dari Indonesia’. ‘Oh, your people still live on trees?’ ‘Masih tinggal dipohon?’ Bayangkan itu ya, hari pertama kita sudah disambut semacam itu.

These experiences implanted a sense of nationalism for Indonesia in Prabowo.

Also, having had his whole childhood to train for, switching between a cosmopolitan who talks like a Westerner and a ‘fist-shaking demagogue’ that appeals to specific sectors of Indonesian society would come naturally for him. This leaves on-lookers wondering: which one is the real Prabowo?

They are both real. To those unfamiliar with the skills of a cultural chameleon, it may seem as though Prabowo is putting on different personas. But acting as a cultural chameleon is a communication skill, not the symptoms of a split personality.

If Prabowo appears to some Westerners as ‘someone who “thinks like us” and talks like a Westerner’, it is because they mistakenly conflate Prabowo’s fluency in English and Western culture-speak with having democratic values that the West tends to associate with itself. Essentially they are saying, ‘You’re not like all those other Indonesians. You’re different because you sound like us.’

It is false to assume that cultural assimilation is a prerequisite to sharing fundamental values, as though the likes of Joko Widodo, a non-Western educated man of humble origins, cannot understand international protocols.

To make it more confusing for the observer is that not only is Prabowo a cultural chameleon, but he is also a political chameleon – two very different skills that are not to be confused with each other. The former allows Prabowo to communicate effectively with different audiences, the latter allows him to change political tunes when it suits him. Over the past decade or so, he went from a military commander who was implicated in the killing of unarmed citizens to a defender of the poor.

In fact, acting like a political chameleon is a common trait among the famous faces in his election team regardless of where they spent their childhoods. Mahfud MD was a vice presidential nominee to Jokowi, but jumped ship after failing in his bid and became Prabowo’s campaign manager. Similarly, Amien Rais was well-known for his role as a spokesperson for the reform movement that brought Suharto down in 1998, but he recently surprised many by backing Prabowo whose campaign harks back to the Suharto era.

Rais’ support came after Prabowo chose Hatta Rajasa from the National Mandate Party (PAN), in which Rais is chairman of the advisory board, as his running mate. It is not the first time that Rais changed his tune. Previously, he was known to be hostile towards the ethnic Chinese and Christians up until 1998 when he realized that he would stand a chance running for presidency once Suharto falls, after which he adopted a more accommodating stance towards pluralism.

If there is one thing that is consistent about Prabowo and his campaign team, it is their willingness to barter political tunes for political gain. It just so happens that Prabowo’s childhood gave him the ability to present these tunes in a cosmopolitan package when it suits.

Danau Tanu completed her PhD in Anthropology and Asian studies at the University of Western Australia on mobility and international education in Indonesia.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss