The Workers’ Party’s (WP) secretary-general Pritam Singh will be conferred the title of Leader of the Opposition, and with it a promise from the government that Singh will be “given the staff support and resources to carry out this role”. While is it still unclear what such resources would be, clearly the most important resource that Singh can get is government information.

Singh is no stranger to lack of information. Just earlier this year, he had some tense exchanges with other Members of Parliament from the People’s Action Party (PAP) about the availability of retrenchment data. In 2011, Singh also made calls for a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) in parliament, citing the need for transparency to ensure citizens continue to trust the government. Pundits commenting on Singh’s new appointment have already suggested that he could be given greater access to government data to aid the work of a shadow Cabinet, including briefings from government ministries, but also point out that this would likely be available only to the Leader of the Opposition.

Access to that data, suggested as an exclusive privilege for Singh, is quite different from the FOIA he proposed. There were two strains of argument in the GE2020 that hinged on the issue of access to information. The first is its value to policy making by both political parties and Singaporeans who have the interest or expertise, and the second is about government trust. These are issues that can only be resolved with an FOIA, and it is worth exploring them cohesively.

The “half-step” debate on policies

There is an inextricable relationship between information and policy, as a good policy proposal is only as good as how closely it relates to everyday life, which is often represented in statistics. Particularly for GE2020, politicians have attempted to distinguish themselves from their opponents by how well they are able to use data in formulating policies.

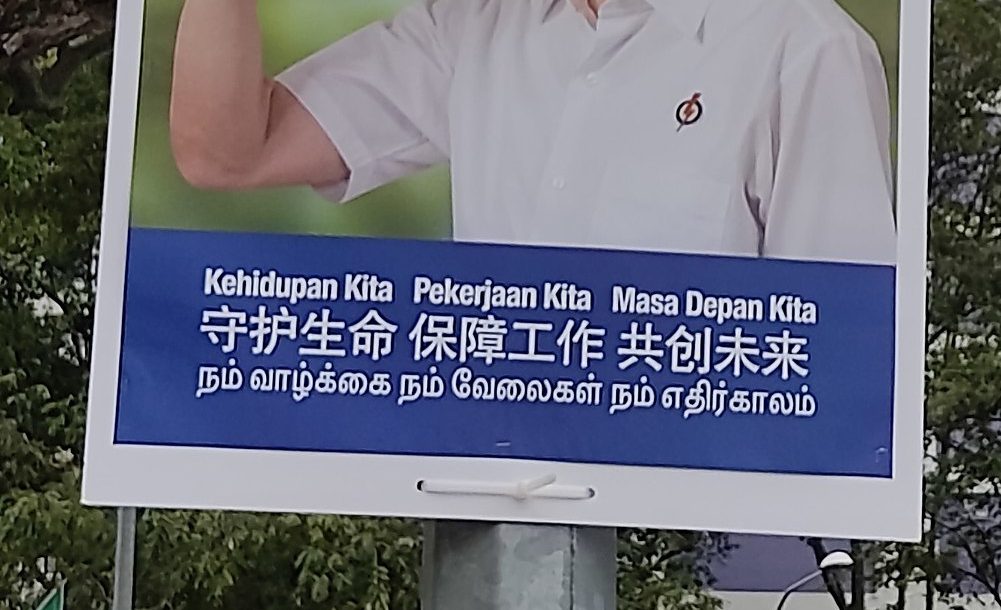

One of the highlights of GE2020 was the first televised debate between the PAP and the three largest opposition parties, in which the WP fielded economics professor Dr Jamus Lim. Lim was engaged in an argument with the PAP candidate over how the WP was a “PAP-lite” that took a “half step to the left” from the PAP’s more conservative and pro-capital policies. Lim pointed out the principled difference of the WP being on the side of labour instead of capital, and that its policy positions were carefully weighed.

While the focus on the details within policies might not have translated massively to votes, GE2020 suggests that a greater focus on the details of policy making, rather than the broad strokes of policy proposals, might be taking hold in an increasingly educated and politically-conscious electorate. There is reason to hope that beyond getting caught up in the battle of personalities, the elections might have sparked an interest among citizens to think more deeply about policy issues.

The use of information serves to distinguish political parties as seasoned players who are serious about making a contribution to government policy. GE2020 might have demonstrated that sheer party branding still retains the strongest pull on votes, but as parties gain traction and younger voters become more engaged, sound policy proposals that affect their lives will be a key distinguishing feature between parties.

The debate over the Net Investment Returns Contribution (NIRC) in GE2020 highlighted this difference. While the WP proposed a 10 percent increase, the Singapore Democratic Party (SDP) had pushed for a flat sum of S$13.3 billion drawn from the unused balance of investment income. This directed the tenor of the discussion from “how are you going to pay for this” towards “how much are you going to commit to this, and why”. The widespread and effective use of information for policy formulation among different parties helps sharpen the distinction between ideas and encourages voter discretion. This can only happen when information is available to all parties, not just a select few.

The grounds-up contribution to policies

It is becoming increasingly unlikely that Singapore can depend on policy makers to come up with policy proposals by working in isolation. As social problems become more complex, our elected representatives need citizens and civil society to pitch in with expertise that comes from people who might not always be willing to stand for election. The advocacy effort to conserve Bukit Brown in 2011 was a significant instance where civil society has demonstrated both willingness and ability to offer alternative solutions to land development policy. The previous administration’s proposal to create a law against ‘fake news’ saw a spirited push-back from civil society and academia, of which many members made submissions to a public consultation process in 2018. Earlier this year, the Freedom of Information Singapore Working Group (FOISG), a collective of Singaporean students, have pushed for a Freedom of Information Bill to be tabled in Parliament, so that citizens can play a role in policy formulation.

The desire among citizens to play a part in policy making cannot be ignored, and an FOIA allows such aspirations to be realised, even when – and especially if – such aspirations comes from outside of Parliament. Such ground-up contributions can no longer be seen as isolated instances of activism, but instead as indicative of a maturing and educated citizenry keen to be heard and to challenge existing ways of governing Singapore. While it may appear adversarial, such activities are beneficial to society at large. They generate new ideas that different sides of the political divide can draw upon.

An FOIA essentially means that citizens are promised the correct and complete set of information on request, rather than relying on their Members of Parliament to ask on their behalf. An FOIA regime can and should also provide for automatic, scheduled release of many categories of information—for instance, quarterly or annual figures of a critical aid programme. It should also include stricter requirements on the government to declassify previously classified information after a stipulated period of time, should there be public interest in it—for instance, the defence commitment for a particularly controversial piece of military equipment. Doing so not only ensures continuity in the flow of ideas, but also allows interested groups to build longer-term proposals that can be tweaked as more information is made available, while also encouraging transparency in governance.

POFMA and the crisis of trust

Perhaps the most urgent need for an FOIA is to build public trust in the government, even if citizens do not use it for policy-building. The Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA) was passed in May 2018, with the purported view of using it to correct online information that the government of the day deems as false and a threat to society. However, the use of the law thus far has been anything but straightforward, leading to long and multi-layered legal challenges against official correction directions.

A key feature of these disputes has been the controversies over underlying facts and figures, where those found to be in breach of the law were blamed for not having the correct data, or to have made statements on official policy based on a different set of data. These included ambiguities about retrenchment figures of Singapore professionals, secrecy over the renumeration of the chief executive of a sovereign wealth fund, and the investment gains and losses of the sovereign wealth funds.

A great deal more transparency on public information would certainly lead to a diminished use of POFMA. Open sharing of public information would effectively mean that anyone seeking to challenge policies or official statements must first refer to publicly available information as established and objective ‘fact’. Thereafter, anything else that follows can only be regarded as analysis or deduction, which then cannot be subject to POFMA. More importantly, information transparency will lend greater credibility to the government, as it would be seen as doing its best to make sure no one trips up over using incorrect, speculative or fabricated data. Such transparency would fend off unease that the use of POFMA might be politically motivated. The very presence of factual and correct information, made available in publicly-known online locations, offers an effective guard against misinformation and a powerful inhibitor to malicious actors bent on disinformation.

There is also a need to distinguish between types of information, as the proper release of each type has a bearing on public trust. There is raw data, such as the quantum of Singapore’s reserves, which office holders have been reluctant to reveal. Reasons given have ranged from the long duration needed to calculate the figure to concerns about national security. Holding back on such data, unfortunately, has the adverse effect of preventing a proper assessment of whether the reserves have been well-spent or properly invested. While raw data can be sensitive, some degree of transparency can help to improve trust that our reserves have not been misused, and allow alternative policies to be crafted to make better use of them.

Another type of information relates to policy deliberation. The most prominent example of this has been Singapore’s population management policy. In 2013, the population size of 6.9 million projected in a White Paper created much public unease and controversy, leading to Singapore’s largest public protest. Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong had to clarify in parliament that the 6.9 million figure was not a target but a planning parameter. Population management again surfaced during GE2020, but this time the number thrown around was 10 million and was the subject of yet another POFMA order. The man behind the controversy, former chief planner Liu Thai Ker, clarified that the figure was, once again, not a target but a planning parameter.

In such circumstances, the exact figure mattered much less than the decision-making process that went on behind the figure, and the government agencies involved in population management would have instilled a lot more public confidence if they had detailed how such parameters were calculated, the reasons behind them, and the conditions under which such an increase would be sustainable. Hence, while some raw data might be considered sensitive, the process of decision-making cannot be treated as such if the wish is for the public to have faith in policy-making that affects their lives.

Problems with FOIA and mitigation

Proposals for an FOIA in Singapore have faced opposition from past administrations. Reasons given include hindering trust in politicians, abuse for profit motivations, and concerns about a downward spiral of frivolous and vexatious requests for information. These concerns have some merit, but there were also complemented with convoluted arguments about an FOIA leading to greater government opacity and avoidance of record-keeping, and the notion that openness might not lead to better governance. This is difficult to swallow when one considers that current official opacity and prospective good policy outcomes are precisely why an FOIA is needed. When queried in 2018 about introducing an FOIA, a PAP office-holder remarked, “I’m sure that will be considered”. To date, no such consultation has been conducted and this is clearly a lost opportunity.

Certainly, countries with an FOIA, like the United Kingdom, have faced issues with odd requests that border on attempts to fulfill personal fantasies and support wild conjecture. However, there is no reason to believe that this has had a negative impact on UK society. Indeed, a 2016 report by the Independent Commission on Freedom of Information noted that while “requests under the Act do impose a financial burden on hard-pressed public authorities”, these were “justified by the general public interest in accountability and transparency of public bodies”. Indicatively, Singapore would do well to consider an FOIA for the benefits it brings to its own reputation as a functioning democracy, rather than just the costs it exacts.

When carrots are not enough: Singapore’s actually fairly exciting general election

...A substantial share of the population wants debate...and a shift from the conceit of “apolitical” technocratic management.

The issues identified are also surmountable. The problem in Singapore is that there has been no publicly-known official effort to study the provision of information to the public as a priority, followed by tackling these issues as by-products of that priority. Solutions to these issues have been proposed by FOISG, who have outlined a number of safeguards to prevent abuse of an FOIA. These include imposing restrictions on personal data, sensitive data that pose security risks, information that can be deemed frivolous or vexatious, and non-existent information. Beyond the type of information, the process by which information can be classified and declassified also needs to be considered. An FOIA needs to assume that publishing information is a given, and restrictions can only be considered on a case-by-case basis, within a stipulated time and procedure for review that has the final aim of eventually making such information fully public. To ease public service workload and acclimatise them to gathering and organising information for sharing, Parliament can pre-agree on information that has to be released for specific programmes. This should be part of the process when ministries seek budgets for their programmes – after all, if Ministers want money, they must be expected to be accountable to the public and provide necessary information, to instil public trust that the specific pot of money is well spent.

Freedom of information is an essential part of any functioning democracy. An FOIA promotes a multiplicity of policy ideas, holds administrations and state agencies to account, and provides a sound basis for public discourse that is free from falsehoods. The issues identified by past PAP administrations are manageable, and processes can be set in place to ensure that the workload on our public service is minimised, while ensuring accountability and transparency in government work.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss