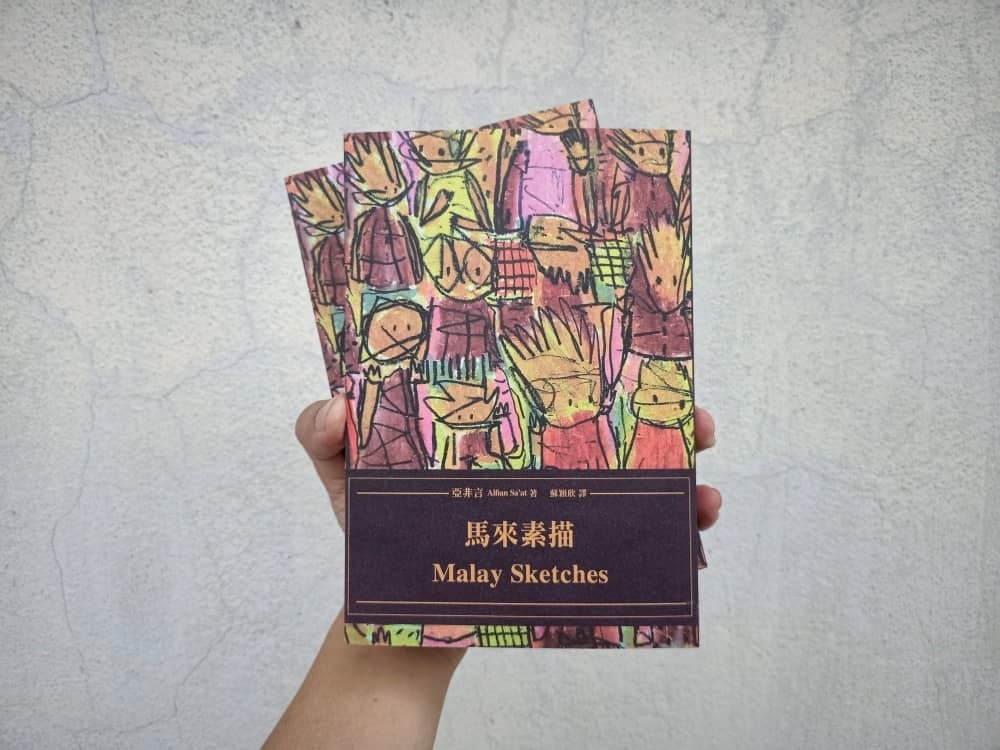

Last year, I translated Singaporean writer Alfian Sa’at’s flash fiction collection Malay Sketches into Chinese for publication in Taiwan. Malay Sketches bears the same title as British colonial administrator Frank Swettenham’s 1895 travelogues whose orientalist portrayal of Malay lives, customs and beliefs has been subverted in Alfian Sa’at’s work, which subtly captures the realities of life for the Malay ethnic minority in Singapore.

As a Chinese Malaysian, I realised that translating an ethnic Malay Singaporean writer’s work, written primarily in English but including many untranslated Malay terms, into Chinese for publication in Taiwan raises many questions. Issues of language politics and the mechanism of literary translation in Malaysia and Singapore need to be unpacked.

The first question that arises is: Why translate the work and for whom? The original audience I had in mind were not Taiwanese or Mainland Chinese but the Chinese-reading public in Singapore and Malaysia. Taiwanese readers who were not familiar with the Malay culture and the Singaporean context would need footnotes. Unlike other, more assimilated, Chinese diaspora communities in Southeast Asia, there are still robust Chinese-reading ecosystems in Singapore and Malaysia, largely sustained by education and media. In Malaysia, ethnic Chinese constitute a minority population (less than 25%), but in Singapore they are the majority (more than 75%). However, the percentage of those who read and speak Chinese is much less. Part of my initial motivation in translating Malay Sketches, which includes many unbelonging minority characters, was to make the dynamics of race relations in both countries visible and relatable.

Recent debates on racism and “Chinese privilege” in Singapore have prompted us to rethink whether racial privilege is always intertwined with the history of colonialism, as well as language and class privilege. It is tempting to view Sinophone and Anglophone literature in Malaysia as the minority and Malay literature as the majority; however, the majority versus minority and dominance versus resistance binaries are not particularly helpful in understanding the multi-layered racial and linguistic relationships featured in Malaysian and Singaporean literature. Examining the politics of literary translation offers a way to identify common ground for relatable and connectable differences.

Translating in the national context

In plurilingual countries, such as Malaysia and Singapore, translation is a daily activity. To a certain extent it is unconscious, and people naturally switch codes in public spaces in vernacular Malay, Chinese dialects, English/Singlish/Manglish, Tamil and other indigenous languages. This is the “rojak” culture of which Malaysians and Singaporeans are so proud. However, such daily crossovers in speech do not necessarily occur in writing. Unlike in films and plays, in which simultaneous subtitles/surtitles serve as a temporary, albeit imperfect, solution to language barriers, the linguistic threshold for literary works is higher. (Interestingly, Alfian Sa’at’s play, Tiger of Malaya, highlights the challenges that arise when characters try to understand each other through translated surtitles.)

In recent years, literature written by migrant workers from South and Southeast Asia began to take root in Malaysia and Singapore. These literary works are inevitably confined in separate linguistic realms and discourses unless translated. Thus, literary translations between languages becomes a conscious, if not political, effort to let one another be heard within the national context.

I emphasise the “national context” because the translation of literary works today is most commonly understood as an inter-national endeavour with two purposes: 1) to introduce foreign authors to the local community (translate in); and 2) to introduce authors from non-Western traditions to the global, often English-reading, public (translate out). Translation in Malaysia and Singapore differs, as it needs to take place both across and within (translate within).

Translation in the national context is a conundrum. First, the dominant role of English over other ethnic-based languages hampers translation between non-English languages. In both countries, linguistic communities are often tied to racial identities—Malay for the Malays, Chinese for the Chinese and Tamil for the Indians—the boundaries of which are difficult to cross in today’s racial politics. These are also the bureaucratically defined “mother tongues” for Singaporeans.

Conversely, despite its colonial legacy and contribution to hegemonic power globally and locally, English is seen by many, especially political elites in Singapore, as a “neutral” language without racial connotations. Notably, translating into English also makes exposure to the global market possible. Conversely, translating into Malay, the national language for both countries, has less value.

The place of publication is also crucial, as the English-speaking West remains the centre for literary publications. This has engendered an imbalanced representation of power among writers in Singapore and Malaysia, as those writing in English and publishing in the West receive much more attention than those writing in languages other than English and/or publishing locally. Sinophone Malaysian (Mahua) writers, such as Ng Kim Chew, Chang Kuei-hsing and Ho Sok Fong, recently received attention from global critics after their works were translated into English and published in the US and the UK. Thus, there is an urge to translate out but not within.

Due to the rise of “Sinophone studies” in US academia, people have started to pay attention to Chinese literature outside Mainland China that challenges the standard form of “Chineseness”. The best example of this type of literature is Mahua literature. However, this also shows that Chinese is never a minority language in the global setting.

In search of a language that unites

The second question is: Why is there a need to translate within if it is accepted that there is one common language that everyone can read and converse in (i.e., English for Singapore and Malay for Malaysia)? In Malaysia, Malay, as the sole national and official language, should theoretically be the language for all Malaysians; however, in reality this is not the case, at least not in literature. Those who admire the function of Bahasa Indonesia blame non-Malays for not speaking and writing “well enough” in the national language and even attribute the lack of success to the existence of Chinese and Tamil vernacular schools. Thus, a paradox emerges in which people celebrate the greatness of “rojak” culture, multiculturalism and multilingualism, but are reluctant to translate within because of the desperation for there to be one language that unites all. As historian Rachel Leow indicates, language diversity is seen by the Malaysian state as a “source of crisis” that needs to be managed instead of a source of “connection, human creativity, and alternative modes of being national.” This can be seen in the controversies that arose in the civil service and at a public seminar in recent years.

To be fair, good intentions underly this desperation: people want to communicate effectively. This was the dream of many anti-colonial nationalists in Malaya during the 1950s and 1960s when movements to learn the national language were initiated by people throughout the new nation. In particular, the Chinese-medium Nanyang University was a stronghold for promoting Malay language and literature among the Chinese community. Its student union has organised Malay language evening classes since the establishment of the university in 1956, and a full-fledged Malay Studies Department was established in 1968.

Malay was celebrated as the national language; however, the use of English in a non-colonial sense and for Third World solidarity has also been considered. Renowned Anglophone writer Han Suyin taught a course called “Contemporary Asian Literature in the Context of National Emergence from Colonialism” at the University, some two decades before the term “postcolonial” was coined by US-based academics. Han Suyin and many Nanyang University students viewed Malay as a language that connects the polyglot society, but also believe that the development of culture and literature written in other languages should be celebrated. Nominating Malay (rather than English) as the national language was a conscious decolonial act. Malay was also seen as a language of liberation.

Further, Malay is a vernacular language in the Andersonian sense that it became the print language for anti-colonial nationalists and later the language of the postcolonial government. The inclusive meaning of Malay as a vernacular language has changed over the years, especially after it became highly politicised and racialised following the 1969 racial riot.

Literary translation flourished in Malaya during the 1950s and 1960s. One could say that it was carried out in the spirit of nation building; however, those experiments seem to have failed. Our generation urgently needs to rethink the following simple questions: Why translate? What is the legitimacy of literary translation within Malaysia now?

For Malaysian scholar and translator Chong Fah Hing, every era needs to develop its own “translation cognition”. He has criticised local agencies that prioritise the translation of classical and canonical Chinese literature into Malay (as a representative of Chinese literature “proper”), but not local Mahua literature. For him, the effect of translation depends on whether the translators have correctly grasped the pulse of times and the needs of their community, and whether they understand the text and context well. He noted that a translator could easily “kill” a writer if s/he is not familiar with the socio-historical context of the literary field that the author belongs to and the characteristics of the writer’s text.

Literary translation is not only about transmitting textual meaning from one language to the other, but also requires cultural and intellectual translation and the understanding of the (un)translatability of the text and context. The local Chinese-Malay translation work (translate within) of the Nanyang University generation, including Liaw Yock Fang, Yang Quee Yee, Chan Maw Woh, Lim Huan Boon, and Leo Suryadinata, was particularly significant precisely because these translators captured the pulse of times and straddled the Chinese and Malay cultural communities. Notably, they bypassed English, the significant pivot language in the field of literary translation. The same can be said about the Malay poetry translation projects of the early 1970s by the Mahua modernist writers, Chong Fah Hing’s Chinese translation of the Malay poetry anthology and the Malay translation of Mahua poetry. Another notable phenomenon is that a translator who translates both from Chinese to Malay and Malay to Chinese is always a Mahua person. Thus, a Mahua translator also needs to translate into a second or third language, a practice not in line with most translation practices.

The myth of a national culture

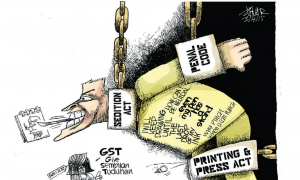

Six decades after independence and the promotion of the Malay language in education, culture and the public sphere, it is worth asking: What fruits have been reaped from those efforts? Are there more non-Malay writers who choose to write in Malay? Did those who complied with the policies receive adequate attention? What developments have there been in Malay literature? Unfortunately, the answers to all these question are in the negative. For a creative writer, choosing not to write in their first language is a conscious, often difficult, decision. Renowned Chinese American poet Ha Jin famously said that to survive as an immigrant after the Tiananmen massacre he was “exiled to English”. The much-gifted bilingual poet Salleh Ben Joned, Malaysia’s late enfant terrible, claimed that it was impossible for him to write in his “beloved mother tongue” in the absence of any response from his fellow Malays. He had to resort to English, even if that is not the language that his “Muse wants to speak in”. The late theatre director Krishen Jit chose to participate solely in Malay-language theatre in the 1970s, but his credibility was disputed by some who saw him as an outsider to Malay culture, which prompted him to revise his views a decade later. The Orang Asli (Semai) writer, Akiya, wrote in Malay, but in a recent talk, he implied the feeling of marginality when facing other Malay writers. A stimulating online forum on the 50th year of the 1971 National Cultural Congress from which the infamous National Culture Policy was created shows how a bureaucratic and exclusivist definition of a “national culture” has undermined our diversity and how artists and writers have tried to subvert it. Despite developing in a direction opposite to what the state desires, the development of Sinophone Malaysian literature has become more institutionalised, and more Anglophone Malaysian authors have received global attention and awards outside Malaysia, which the state chooses not to recognise. Paradoxically, the Malay language has become the most policed language in Malaysia. As Eddin Khoo pointed out in the forum, Malay culture itself is the greatest victim of the policy, as it carries the burden of becoming a national culture” at the expense of eliminating its own heterogeneity. The policy has not built a national culture, but a culture of resentment.

When a local language is elevated as the language-of-power, especially when the language is knitted together with racial privilege (Malay in Malaysia) or global hegemonic power (English in Singapore), great efforts are required to unpack the power dynamics and the politics of language. One way of doing this is to encourage literary translation from within and revitalise the vernacular nature of language.

Revitalising the vernacular

What is the “vernacular” in Singapore and Malaysia? In Singapore, it refers to mother-tongue language education in Chinese, Malay and Tamil, and the publication of newspapers and press in these three languages (i.e., non-English). In Malaysia, vernacular schools mean state-funded Chinese and Tamil schools which educate around 22.5% of Malaysian primary students. These are often seen as a stumbling block to national unity and have always been a target of criticism.

In Malaysia and Singapore, the vernacular has become the antithesis to the national and the official. Interestingly, the Malay language in both countries can be considered both a national and vernacular language. It is national as stipulated by both states (albeit many Singaporeans do not speak their national language), and it is vernacular as practised by the people. For example, if we consider the role of English in the media and education in Malaysia today, particularly in the case of previous Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamed’s stubborn insistence that Science and Mathematics be taught in English in schools (PPSMI) and the movement to abolish the policy (Gerakan Mansuhkan PPSMI), Malay can also be considered the vernacular language of Malaysia.

The vernacular language originates from a decolonial nationalist endeavour to challenge hegemonic power; however, this endeavour should not, in turn, become a hegemonic power itself. Indeed, the vernacular is a language that wants to include, communicate, empathise, understand and have dialogue with others.

The vernacular can also become an “echo chamber” if discourses are kept in separate linguistic realms and isolated from others. This is where translation should enter. Translating within is a vernacular effort to connect and not to segregate. Interestingly, while Malay Sketches was written primarily in English, the author, Alfian Sa’at, found himself translating his character’s voice from Malay to English in the writing process. In a personal communication, he stated:

I decide between translation strategies: to “domesticate” the text so that it appears readable, as if it was originally in English, or to “foreignise” it, so that there are traces of the original language, even if it may be jarring. It can be an interesting experiment in creating an in-between language, where the words appear in English, but the syntax and the rhythm of the line sound like Malay.

This inherent translation process has made the English in Malay Sketches a vernacular language too, as it wrestles with and disrupts the standard form of language. Similarly, Sinophone languages in Malaysia and Singapore are not standard Chinese. In my translation, in which Alfian Sa’at’s Malay characters speak Sinophone, I tried to use local expressions, but some terms had to be modified for Taiwanese readers. For example, in Malaysia and Singapore, people often use transliteration to refer to foreign words, such as luo li for lorry and de shi for taxi, but in the Taiwanese lexicons the terms ka che (truck) and ji cheng che (metered vehicle) are used. These terms are also different in Mainland China. It is always a challenge in literary translation to balance the demands of the original texts, the agency of the translator and the demands of the imagined readers.

Translating the vernacular from within

Unfortunately, productions of and discussions about literary translation are still rare in Malaysia compared to Singapore, which has more institutionalised supports such as the National Arts Council and Singapore Book Council. In recent years, the Georgetown Literary Festival in Penang has invested serious efforts in kickstarting the conversation. An analyst also suggested the literary translation hub shift from Kuala Lumpur to the island. Nevertheless, comparative studies on the literature of different languages in the national context are also scarce. It is my view that more meaningful discussion will be created when we compare Anglophone literature in Malaysia and Singapore with other Malaysian and Singaporean literatures, instead of relating them to global postcolonial literature. The same can be said about Sinophone Malaysian and Singaporean literature, as they make less sense in relation to global Chinese literature than that suggested by Sinophone scholars in the West or overseas Chinese scholars in China.

“Malaysia” and ”Singapore” do not refer only to a rigid idea of a state, but also a symbiotic community, a collective history and a living place with which people identify. In this respect, writers from Borneo further manifest their distinctive linguistic and national identity and thus trouble the neat categorisation of race and language on the Peninsular. A telling example is Malaysian writer and translator Pauline Fan’s recent award-winning English translation of Sarawakian poet Kulleh Grasi’s Tell Me, Kenyalang, which was originally written in Malay alongside Iban and various indigenous languages. The book was published in New York and could easily be seen as a practice of translating out. However, it is arguably done in the spirit of translating within, as it disrupts the paradigms being played out in Malaysia’s language and race politics.

My intention to translate Malay Sketches into Chinese reflects a similar desire. However, the fact that my translation was published in Taiwan but not within also shows that language paradigm constraints in Malaysia and Singapore still exist and need to be overcome. Transnational collaborations might offer a way to address these problems. Sometimes one has to make a detour or multiple detours to reach home.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss