How many ways can you protest an election? Many, as Thailand has showed. The 2 February 2014 national election was likely among the world’s most bizarre voting days, with incidents ranging from “missing” polling stations to a shooting match complete with M16. Electoral irregularities are normally caused by the incumbent to improve their chance of winning, but in the Thai case, at least 2 million Thai voters were unable to cast their ballots because of their own peers.

Figure 1: Types of Protest Voting in the 2014 Election

| Descriptions | 2014 Election* | Implications | |

| No Vote | Not voting at all | Voter Turnout 47%;No Vote 53% | A high “no vote” means a low voter turnout but no effect on electoral outcome |

| Vote No | Casting ballot but voting for no one | Vote No 17% | If constituency A has more “vote no” than the candidate running (must be the only one), then a by-election is called |

| Invalid Vote | Casting ballot incorrectly | Invalid ballots 12% | Implications only if invalid votes higher than votes to a candidate running in a particular constituency |

| Vote Obstruction | Preventing others from casting ballots | Est. 2 millions+ | Obstructing others from voting or tearing up ballots is violation of the electoral and criminal laws |

*Results not including the 9 provinces in southern Thailand

Electoral protest in Thailand, however, goes far beyond merely punishing an incumbent. While it is a protest against the incumbent at one level, “protest voting” in the 2 February election was also in opposition to the idea of electoral democracy itself. There were four major types of protest voting: 1) No Vote; 2) Vote No; 3) Invalid Vote and 4) Vote Obstruction. Not all these forms of protest voting have legal bearing on the election results, but they all point to different ways voters can both erode electoral support and weaken the legitimacy of the incumbent.

The “No Vote” campaign launched by the People’s Democratic Reform Committee (PDRC) was a protest against the electoral system, not just the election. Under the leadership of former Democrat Party strongman, Suthep Thaugsuban, the No Vote movement is an anti-election campaign against what they see as a corrupt and unjust electoral system. Supporters of the No Vote campaign strongly believe that a low voter turnout would help debunk the “myth” of Pheu Thai’s popularity. Symbolically, the fewer the people exercise their voting rights, the more people are upset at the current electoral arrangement.

As a main strategy for the People’s Alliance for Democracy (PAD) in the 2007 and 2011 elections, the Vote No movement aims to not only “steal” votes away from going to any particular candidates, but it can prompt a by-election if the shares of Vote No are higher than those received by a candidate, in a constituency with only one candidate running. In theory, this campaign makes more sense than its No Vote counterpart because it has real implications for the electoral outcome. However, the failures of the PAD’s Vote No in the previous two elections made this strategy unappealing to the PDRC.

Casting an invalid ballot on purpose is also another way to make a protest vote counts. A clear sign that an invalid ballot is considered a protest vote is when comments are written on the ballots showing the voter’s intent. The last form of protest voting involves obstructing others from casting their ballots. Through coercion, many of the PDRC supporters have set up (human) barricade or encircled polling stations to cause an “automatic No Vote” when voting is called off in certain districts.

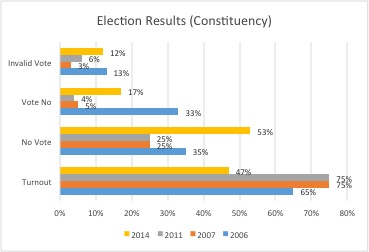

Figure 2: Results in constituency elections (2006-2014)

At a first glance, the unofficial 2014 election results (excluding the 9 southern provinces) show a much lower voter turnout than in the previous elections. At 47%, voter turnout this round was nowhere near the high of 75% in the 2011 and 2007 elections, and much lower than the boycotted 2006 election. Although not all 53% No Vote were supporters of the PDRC, the movement will surely take credit for their “success” in convincing people to forgo their voting rights.

If the main aim of the No Vote campaign is to discredit the electoral system, then its success must be qualified given the Vote No shares and invalid ballots in the 2014 election. Vote No accounts for voters who still believe in electoral democracy because they continue to exercise their rights even though they vote for no one. The 17% Vote No is much higher than the 4%-5% in 2007 and 2011 elections (although much lower than the 2006’s 33%) still signifies some degree of belief in the electoral system among the electorates. The 12% invalid ballots also account for those committed to electoral democracy.

Ultimately, what the early election results have shown is three things. First, Pheu Thai will emerge as a “weakened” winner. There is no doubt that in both constituency and the PR systems, the incumbent will grasp electoral victory. What they have lost is support from the electorate, particularly some alarming results in the party strongholds in the North and Northeast. The PDRC met with some success in mobilizing the No Vote and will take credit for the rest of the non-Pheu Thai votes in their next move to demonstrate the illegitimacy of Pheu Thai. Third, Thai electorates have shown that despite the lower voter turnout, more than 50% of the country still wants to decide their government at the ballot box.

Aim Sinpeng recently completed a PhD on Thai protest politics at the University of British Columbia, Canada

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss