Nine months since the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) retook the city of Marawi from a coalition of Islamic State (IS) affiliated groups, resulting in the deaths of at least 802 militants, 160 government forces, and 47 civilians, President Rodrigo Duterte signed the Bangsamoro Organic Law (BOL).

The legislation grants political and financial autonomy to a new Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in the Southern Philippines after decades of insurgency and years of tumultuous peace negotiations. Promisingly, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) voiced its satisfaction with the legislation, and is working towards the next steps of implementation, including the decommissioning of 30,000-40,000 fighters. Nevertheless, the BOL must still overcome a range of challenges, including efforts by IS-affiliates to spoil the prospect of peace in Mindanao and Sulu.

Speaking on behalf of the IS-aligned faction of the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF), Abu Misri Mama derided the BOL as an agreement that will benefit only the MILF, and warned of future attacks in response. Although the AFP dismissed the threat as empty propaganda, continuing clashes with the BIFF in Maguindanao and Cotabato lend credibility to Abu Misri Mama’s announcement. The BIFF, like the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) and the Maute Group, reject the notion of autonomy for Muslims in the Southern Philippines, and seek to create an IS Wilayat (province) in Southeast Asia; a casus belli that resonates with and attracts fighters from Mindanao, Sulu, and abroad.

Small and fragmented though they are, the BIFF, the ASG, and the Maute Group are resilient organisations that have defied the AFP’s attempts to stamp them out, and there is no better illustration of that resilience than the AFP’s victory in Marawi.

Based on the number of incidents and associated casualties inflicted by Philippine IS-affiliates before, during, and after the Battle of Marawi, IS-affiliated violence in the Southern Philippines is on the rise. Established in January 2016 by Angelica Mangahas and myself, the Political Violence in the Southern Philippines Dataset codes incidents of political violence occurring within the administrative boundaries of Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago from January 2016-June 2018.

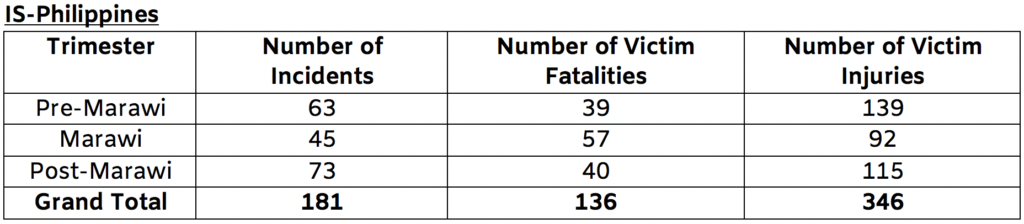

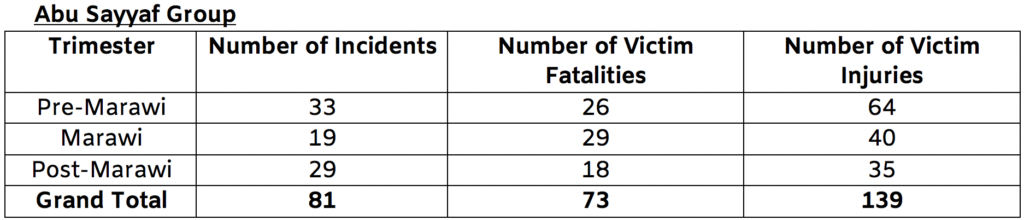

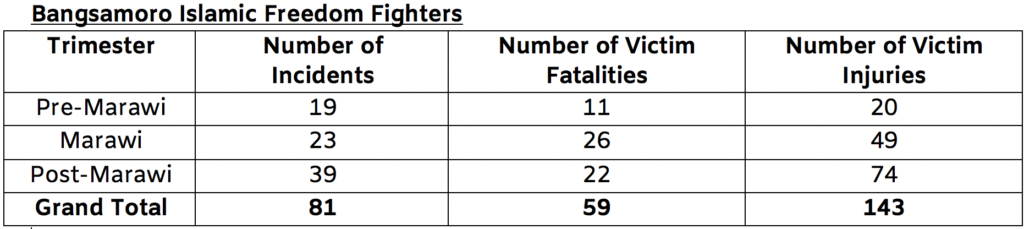

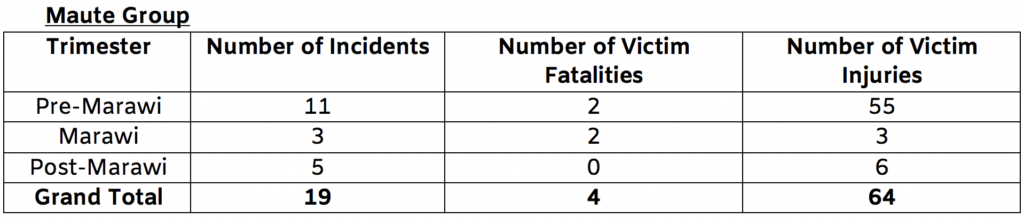

The set records 918 incidents of violence perpetrated by 8 general categories of conflict actors, which includes the ASG, the BIFF, the Maute Group. To interpret the impact of the Battle of Marawi on IS affiliates, namely the BIFF, ASG, and Maute Group, I divided my data into six-month trimesters labelled the “Pre-Marawi” period from November 2016–April 2017, the “Marawi” period from May 2017–October 2017, and the “Post-Marawi” period from November 2017–April 2018.

By segmenting the time series into equal samples, I avoid overweighting the Pre-Marawi period by excluding 134 IS-affiliate incidents occurring from January 2016 through October 2016, in contrast to just 21 incidents between May and June 2018, i.e. the Post-Marawi Period.

IS affiliates engaged in a combined total of 181 incidents inflicting 136 fatalities and 346 injuries. During the Battle of Marawi, the number of incidents declined, only to increase to 73 incidents in the Post-Marawi period. Lethality increased appreciably during the Marawi and Post-Marawi periods as well, while the number of injuries declined. The dip in incidents during the Marawi period may be due to the opportunity costs of maintaining the siege, which could have left groups unable to engage in other attacks. Since Marawi, the number of incidents has surpassed previous levels, indicating that violence is gradually escalating in the region. Considered at the provincial level, however, it becomes clear that this violence was not evenly distributed.

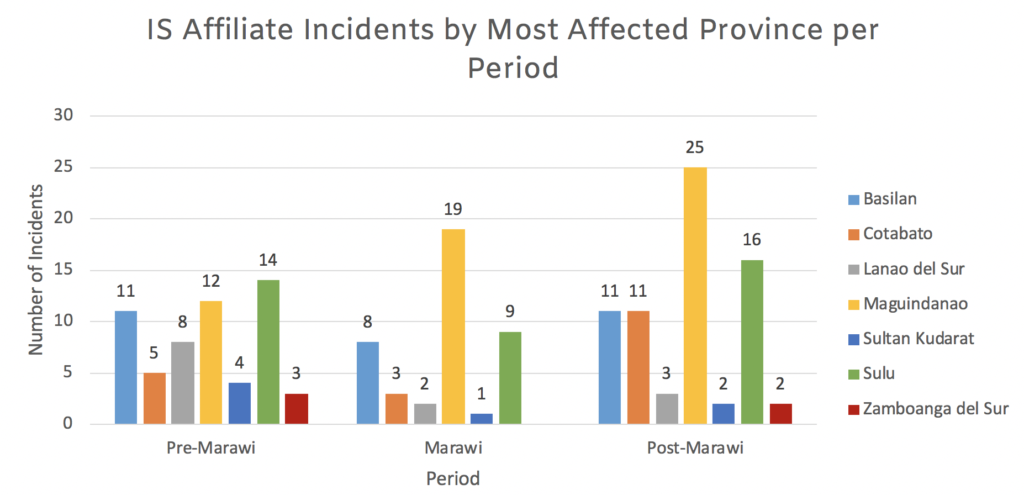

Figure 1: Does not include provinces with only 1 recorded incident per period: Tawi-Tawi, South Cotabato, Zamboanga Sibugay, and Lanao del Norte. Independent municipalities such as Zamboanga City, which is governed independently from the province it is located in, Zamboanga del Sur, is considered part of the province for analytic purposes, following the standard practice of the Philippines Statistics Authority.

Across all 3 periods, the IS affiliates were most engaged in the provinces of Basilan, Cotabato, Lanao del Sur, Maguindanao, and Sulu. Maguindanao, the primary base of the BIFF, was the only province to endure a steady growth in the number of incidents across all periods. All other provinces experienced a decline in incidents during the Marawi period, followed by a rebound in those numbers. For Cotabato and Sulu, the rebound in incidents Post-Marawi exceeded Pre-Marawi levels, whereas in Basilan, incident levels before and after Marawi were equal. In Sultan Kudarat, Lanao del Sur, and Zamboanga del Sur, the Post-Marawi rebound was lower than their Pre-Marawi levels. Ultimately these fluctuations are best explained by the specific activities of each IS affiliate during each period, since they contributed different levels of violence to distinct provinces.

In terms of the number of incidents they engaged in, the ASG mirrors the combined trend of all IS affiliates. Most ASG incidents occurred in the Sulu Archipelago, although Post-Marawi incidents tended to be smaller in scope than those during Pre-Marawi period. The majority of all incidents were armed assaults involving firefights between the ASG and security forces, often within the hinterlands of Basilan and Sulu, but also in urban centres such as Patikul. Despite a decrease in maritime kidnappings in recent years, the kidnapping of local residents of Sulu, Basilan, and the Zamboanga Peninsula by the ASG and affiliated gangs remains a regular occurrence. This data suggests that the ASG has not so much declined as returned to their Pre-Marawi modus operandi.

Unlike the ASG, the number of BIFF incidents, fatalities, and injuries increased steadily and significantly across each trimester. The BIFF was responsible for all incidents in Maguindanao and Cotabato, engaging in armed assaults against security forces and frequent bombings against civilian, military, and police targets. The clear growth in almost all dimensions of their operations indicates that the BIFF took advantage of their more limited participation in the Battle of Marawi, and the subsequent AFP preoccupation with “mop up” operations to establish themselves in Maguindanao and Cotabato. According to local reports from the area, the BIFF has become so entrenched in the Liguasan delta that residents who rely on the watershed to make their livelihood can no longer fish and travel safely, while thousands more are displaced by AFP operations targeting the BIFF.

Finally, the Maute Group’s incidents, the majority of which occurred in Lanao del Sur, declined by about half of its Pre-Marawi total during and after the battle, while fatalities ceased in the Post-Marawi period and injuries dramatically declined. For most militants,

Terrorist arbitrage in Southeast Asia

Jihadists know how to take advantage of the unique space for mobilisation offered by the Indonesia–Malaysia–Philippines triborder area. Governments are still catching up.

While the Maute Group recovers and the ASG returns to (criminal) business as usual, the BIFF continues to evade state forces and thrive in the Liguasan delta. As the data suggests, victories like Marawi are short-lived, due in part to the AFP’s inability to “finish the job”, which results in the displacement rather than abatement of violence. The passage of the BOL will hopefully lead to more effective collaboration between the AFP and the MILF to prevent this cycle of violence from recurring. If the BOL falters or falls short of its promises, however, defections from MILF commands into the ranks of the purported Southeast Asian Wilayat of the Islamic State will become a serious concern for the nascent Bangsamoro government.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss