Thailand’s police and military have been leading operations against the controversial Dhammakaya Buddhist temple complex in the search for a wanted monk. But the raids are a mere dash for cash by the country’s ruling junta, writes James L Taylor.

This may not be my kind of Buddhism, but what is going on against the Wat Thammakai/ Dhammakaya movement is puzzling and intensely concerning.

The junta is taking assets from the temple under the pretence of “reform” without having enacted any proper legal precedence or law. The junta’s action, ideology aside, is connected with the capturing of temple finances across many wealthy (Mahanikai) temples as the regime desperately tries to capture power and bolster its dwindling and misspent state coffers. Other temples which may later be targeted include Wat Saket, Wat Sothonwararam (Chachoengsao), Wat Wat Phra Si Rattana Mahathat (Phitsanalok), Wat Phra Pathom Chedi (Nakhon Pathom), Wat Yai Chai Mongkhon (Ayutthaya) and Wat Rai Khing (Nakhon Pathom).

In the process, there is an attempt to dissolve the Buddhist Association of Thailand (Samnak Phut) and amalgamate under the Religious Affairs Department in the Ministry of Culture to take responsibility for controlling all national temple finances and assets. The regime also intends to cancel the 1962 Sangha Act, amended in 1992, dispose of the Council of Monk Elders (Mahathera Samakon), and bring back the 1941 Sangha Act. It also intends to regulate the personal financial practices of monks and monasteries, restrict monks from disrobing following South Asian precedence, and reform monastic education.

The authoritarian and forceful manner in which the junta is carrying out its purge does not hearten for popular support. In raiding Dhammakaya, the motivation is clearly about money, claimed as illicit to justify its actions.

The Dhammakaya movement may well be a mass spectacle, some people regarding it as specious in its mass production of a neoliberal, commodified (global) religiosity, though in the last decade or more it has been largely discreet and remained outside of any political alliance. However, attacks against the movement’s elderly (and seriously diabetic) spiritual leader Phra Dhammachayo (born 1944), begs for an unbiased and reasoned critique. The Dhammakaya Foundation became a United Nations-accredited non–governmental organization in 1986 and this incident will gain some international attention.

The movement has been under the public spotlight since I first wrote about it in the late 1980s, but is now relentlessly pursued by DSI, the “independent” Department of Special Investigation of the Ministry of Justice, in a case that in fact goes back to 2006 and is likely to become explosive. The events of the past few weeks have even drawn in the outspoken neighbouring ultra-nationalist Burmese monk Ashin Wirathu and monks across Asia in support of the besieged expansive temple complex at Pathum Thani, to the north of Bangkok.

The boss of DSI, appointed to pursue the case in 2016 against Dhammakaya, is Police General Paisit Wongmuang, who is acting on a letter of complaint signed by Paiboon Nititawan, ex-Chairperson of the Reform Committee on the Protection of Buddhism; Dr Mano Laohavanich (formerly Dhammakaya scholar monk, Mettanando Bhikkhu); a network of people affected by the credit union debacle (discussed later), and the conservative Women’s Network for the Protection of Buddhism.

The problem started with the ultra-nationalist junta-favourite monk Buddha-Issara, in a complex plot to destroy Dhammachayo (linking him fictitiously to Thaksin) and to fail the then Mahanikai Acting Supreme Patriarch Somdet Chuang of Wat Pak Nam, the original spiritual source of Dhammakaya. Somdet Chuang criticised Buddha Issara and PDRC (the reactionary “People’s Democratic Reform Committee”) when they illegally occupied government offices prior to the last coup.

The regime sees the annihilation of the Dhammakaya movement as a step towards dissolving the sangha’s supreme power and authority, and emplace instead a compliant civilian administration following Phutta-Issara’s suggestions. The junta in essence wants to completely eliminate any future power and opposition to its absolute totalitarianism.

The Dhammakaya temple is not without influential supporters, though mostly associated with wealthy urban middle class, and the nouveau riche. At times in the past it has been visited by members of various political parties and elites, including the current king (then Crown Prince), and Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn, the latter laying the foundation stone for the Ubosot (Pali: uposathagara) in December 1977.

The military, following the successful 2010 strategy of attrition and encirclement of protestors are only letting people out and not in, and now have mobile medical facilities ready for the final incursion. There are about 10,000 lay persons and monastic sangha at the Pathom Thani temple with raw food not allowed inside, only cooked food sent in which is inadequate and in any case mostly rotten by the time it gets inside. The military (using their compliant police department), under Article 44, are of course outstanding practitioners at “cracking down” on their own protesting civilians. The whole area around the monastery is suffering socially and economically because thousands of people rely on the temple for their livelihoods, and those who work outside the area have to find alternative longer routes. It should also be remembered that there are usually more lay people residing in the temple than monks and novices. A local resident Anawat Thanacharoennat (64) recently suicided in protest of the use of Article 44 against the temple (for more see here).

What is the fascination or desperation in capturing Abbot Dhammachayo? Self-styled PM Prayuth Chan-ocha says it does not matter how long it will take the more than 3,000 police and army personnel (each paid Baht 400 per day) recently boosted again in numbers, but they will stay on until he is found. In fact, monks and laity have not seen him for some time in any case. Prayuth has also now placed a DSI official Pol Lt Col Pongporn Pramsaneh in charge of the National Office of Buddhism in his frustration in not arresting Dhammachayo.

Although long known for astute marketing, Dhammachayo is charged with “money laundering” and racketeering in a case which has many sticky fingers, and as many holes as a leaky bucket. The monastery received a large donation from the Klong Chan Credit Union Cooperative (comprising 52,000 members). The ex-head of the credit union Supachai Srisupa-aksorn is now serving 16 years’ jail time for embezzlement after dishing out a massive 11.3 billion Baht (878 cheques issued through 10 Thai banks) of members’ money to six main organisations and numerous linked groups and individuals (see here and here).

The groups who received money (many of them obtaining sums far exceeding Dhammakaya) have not been charged; it is only Abbot Dhammachayo who is hunted. The religious movement has claimed that it has repaid the money donated from the union, after realising the problematic source of the payment. The credit union said that henceforth they have no issues with the temple. However, DSI (whose boss was not long ago replaced for not bringing the temple down) have not stopped and continue to pursue the hapless religious leader.

DSI and the Office of the Attorney General apparently recouped Baht 3.8 billion, and no one, seemingly, knows where the money is. The credit union’s new chairperson (Mr Prakit Pilangasa in interview on Satellite Channel 29, and Digital TV Channel 19, interviews 23 and 24 February 2017) plans to take legal action against DSI and the Attorney General to recover this money.

There are a number of rumours circulating in the alternative media as to why DSI and the military needs to destroy not just Dhammachayo, but likely uncomfortable incriminating evidence, which they assume may be held at the temple. It must also be remembered that Dhammakaya holds massive wealth, which the military junta, spending money copiously on itself and its schemes, would appreciate to bolster the dwindling national reserves.

There are some other factors in this complex mix: Thailand’s reactionary (pro-amaat) mainstream media were and remain quick to make a connection to Thaksin, groundlessly and mischievously alluding to Dhammakaya as a bastion of the former pro-Thaksin politicians — mainly through a couple of people who were known to have frequented the temple on more than one occasion, such as the former Minister of Public Health, Sudarat Keyuraphan (also see here).

After all these years, the amaat regime are still taking every opportunity to discredit and completely eradicate Thaksin and his former popular political interests. Neither, it should be noted, is the temple “red” — in a general sense it is far from it, if anyone knows followers of the temple. Although there may well be some “red” devotees, like all sectors of societies, it is not clear cut. The media cunningly note the “alleged links” to Thaksin – enough to further discredit the temple, but they never provide any evidence. An allusion, for a particular purpose, is taken as a statement of truth.

A number of points following the above discussion also need to be mentioned with a bearing on the establishment’s desire to get rid of the movement.

First, Dhammakaya is Mahanikai/Mahanikaya. This Thai Buddhist fraternity is not favoured by royalists consolidating attention, symbolic capital and resources through a number of Dhammayut royal temples. As noted above, we saw recently the implications of the amaat decision to dump the Mahanikaya Acting Supreme Patriarch (Somdet Chuang) in favour of a royal Dhammayut monk from the favoured Bangkok Wat Ratchabophit. The Thammakai are targeted for new purges to capture assets.

Second, the idiosyncratic temple has not been known to overtly support the palace with necessary liberal merit donations. This is not a good move, and unlike establishment temples and many famous elite patronised forest monks.

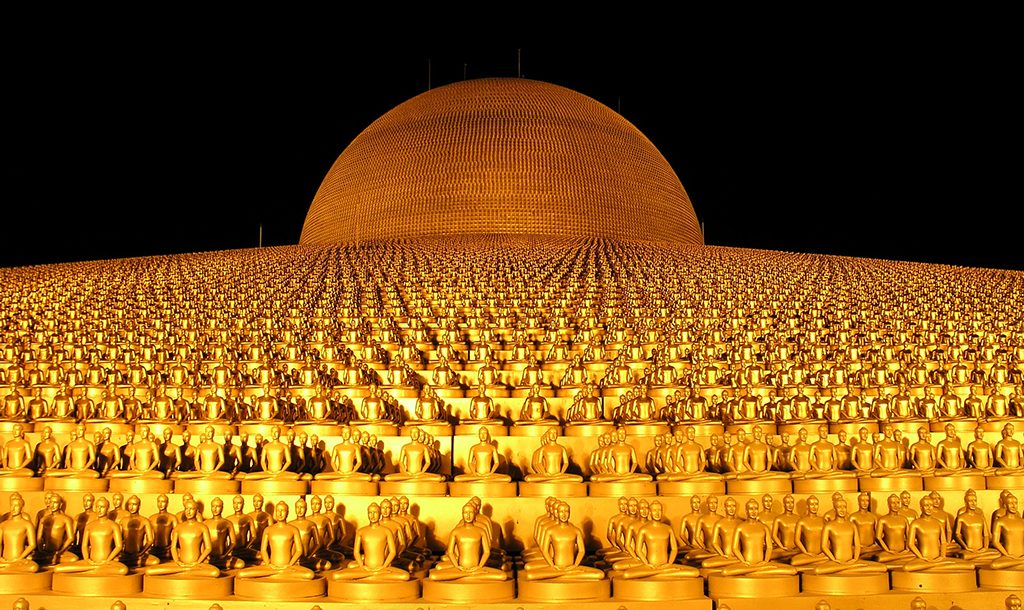

Third, as noted earlier, Dhammakaya is immensely rich. Many devotees for instance initially donated massive amounts of gold in the building of the expansive Cetiya and its Buddha images at the Pathum Thani temple.

Fourth, the movement is global in reach (with 200 branches worldwide), appealing to conservative rationalists; it is stoically politically neutral, aloof, and does not necessarily show favour to those above who it should favour for regal benefice and protection.

Fifth and finally, the movement’s commanding religious and monetary autonomy is worrying for the military royalist establishment who need to control the significant wealth of its national institutions, religious and secular, for its network personal benefits. This is part of a broader agenda of capturing monastic wealth for the benefit of the military regime and its programs.

Dr James L Taylor is Adjunct Associate Professor, Anthropology & Development Studies, University of Adelaide. He has written extensively on Thammakai since the late 1980s and 1990s including in his book Buddhism and Postmodern Imaginings in Thailand.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss