Last week, former US President Barack Obama and his family visited Indonesia, where they followed a well-worn tourist trail from Bali, across Java to Yogyakarta, and finally to Jakarta. Obama has a special connection to the country – particularly Jakarta, where he lived for several years as a child, and also Yogyakarta, where his mother conducted research for her doctorate.

Post-presidency, much has been made of the fact that Obama is living his best life, and his trip to Indonesia has been no exception.

Although he made a speaking appearance at the Indonesia Diaspora Congress, the purpose of Obama’s trip to Indonesia was mostly personal. Nevertheless it was hard not to miss the symbolism of this former President’s visit to a majority Muslim country, at the same time as his successor in the White House seeks to minimise travel by Muslims to America.

From white-water rafting in Ubud to visiting the UNESCO World Heritage sites of Borobudur and Prambanan, Obama’s visit to Indonesia provided plenty of photograph-friendly moments for the former first family – and an expected boom in foreign tourism dollars.

White water rafting in Bali. Image: TMZ

Visiting the temples of Borobudur and Prambanan in Central Java. Image: Daily Mail

Performing independence

Obama is just one of a long line of politicians and celebrities (or, in Obama’s case, celebrity-politicians) to visit the 9th century temples of Borobudur and Prambanan.

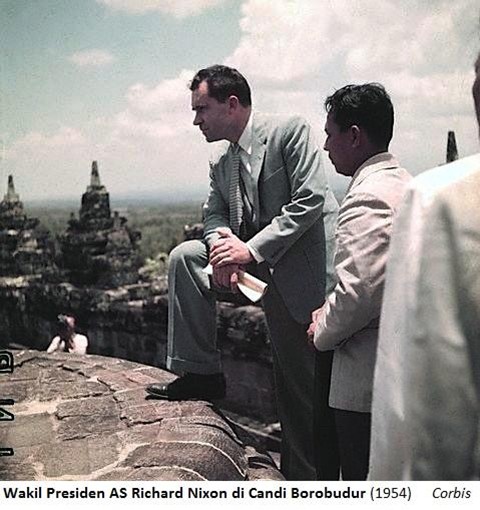

In 1950, for example, Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru visited Borobudur with his daughter Indira Gandhi. Richard Nixon – then Vice President of the United States – was also photographed surveying the view from the temple’s massive upper terrace in 1954. Other visitors included King Norodom Sihanouk from Cambodia, President Quirino of the Philippines, and Prime Minister U Nu of Burma.

Indonesian President Soekarno welcomes Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, and his daughter Indira Gandhi, to Borobudur in 1950. Image: Tropenmuseum

American Vice President Richard Nixon on Borobudur’s upper terraces, 1954. Image: Indonesia Zaman Doeloe

These were performative acts of legitimisation. Following Indonesia’s declaration of independence in 1945, the new nation had turned its attention to modernisation and the need to articulate a unifying national identity. The temples were central to this vision for the future, which was at the same time deeply enmeshed with the glories of its past. As Marieke Bloembergen and Martijn Eickhoff have observed, the temple visits were:

…significant public performances: they helped to legitimise Indonesia as a modern independent state that seriously cared for its beautiful national (and trans-Asian) Buddhist/Hindu heritage. The temples became an important tool in Indonesia’s cultural diplomacy. These monuments made “Indonesia” and its national archaeological monuments more visible on the world map.

“Discovery” and recovery

Pre-independence, European colonists had also recognised that they could use these ancient sites to make a statement about the (colonial) future.

According to William Chapman’s A Heritage of Ruins, it was not the Dutch but the British who possessed ‘the leisure, curiosity, and a special quality of romanticism to bring the ancient, decaying monuments into focus.’ During the British interregnum in Java (1811-1815), Sir Stamford Raffles initiated a program of cleaning and restoration at both Borobudur and Prambanan. When the Dutch returned to Java in 1815, they established a colonial archaeological service, and local and foreign photographers were commissioned to document and record the monuments.

A watercolour painting of Borobudur by Raffles, c. 1814. Image: British Museum

Daguerrotype of Borobudur by Adolph Schaeffer, 1845. Image: Asia-Pacific Photography

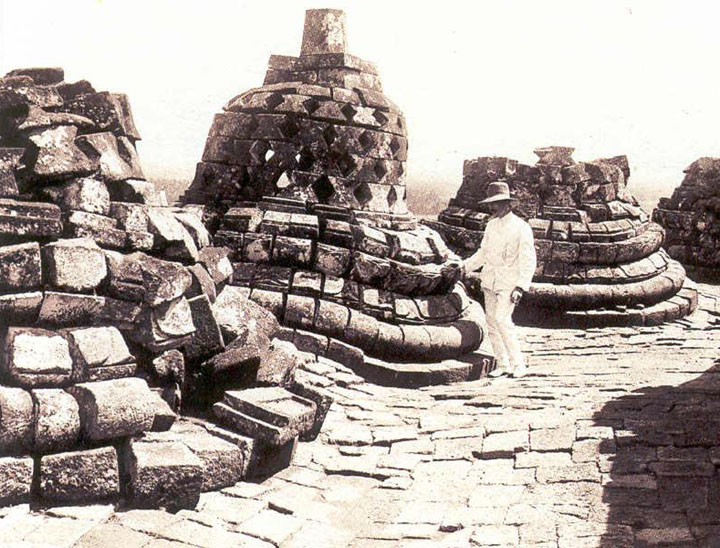

Dutch engineer Theo van Erp on Borobudur’s upper terrace, c. 1902. This photo shows some of the challenges the Dutch colonial archaeological services faced in restoring Borobudur. Van Erp was instrumental in developing ideas to protect and restore the monuments, one of which was to erect a large metal ‘umbrella’ to protect Borobudur from rain. This idea was never implemented. Image: William Chapman, A Heritage of Ruins, 2013.

Benedict Anderson has observed that sites such as Borobudur and Prambanan were successively ‘disinterred, unjungled, measured, photographed, reconstructed, fenced off, analysed and displayed’. Raffles’ restoration programs were linked to the idea that he had ‘re-discovered’ the temples, and the Dutch archaeological service had been developed with protection and preservation – from the ravages of rain, jungle, earthquake and volcanic ash – in mind.

These colonial narratives of discovery and recovery effectively negated the fact that the monuments had been part of the social and cultural landscape – notwithstanding changes in their usage – over centuries. For example, scholars remind us that a local awareness of, and respect for, Hindu and Buddhist holy places in Java was maintained by Indonesian Muslims both before and during the colonial period.

Although the Dutch sought to position themselves as ‘benign caretakers of the previously neglected ruins of great Hindu civilisations’, these restoration activities were not acts of generous colonial benevolence. As Susie Protschky says,

To unearth the secrets that might be embedded in antique temple structures was not only to reconstruct Java’s past but also to command its future, through knowledge, oversight and organisational vigour.

Restoration activities were racially segregated: the Dutch provided managerial authority and the Javanese provided the labour. Not only did this arrangement privilege the agency of Europeans over Asian pasts, it also ensured that this inequality continued into the future.

Furthermore, by deeming these Hindu-Buddhist monuments of the past to be worthy of restoration, the Dutch were better able to undermine present-day Javanese civilisation, particularly in its Islamic modes, and thus to entrench themselves more firmly in positions of authority.

Temples that tweet

Decades later these temples are still being put to strategic use. These days it is less about commanding Java’s future, and more about the economic potential inherent in the temples.

In 2014, the very first photo that Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg posted from his trip to Indonesia showed him meditating (to the extent that you can meditate while being photographed for social media) on Borobudur’s upper terrace. Indonesians are among the world’s most enthusiastic users of social media, and the photo was nothing if not strategic: Zuckerberg was in Indonesia seeking to increase Facebook’s market share.

Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg meditating on Borobudur’s upper terraces at sunrise, 2014. Image: Facebook

Following Obama’s visit last week, Borobudur’s official Twitter account (yes, you can tweet Borobudur, and also Prambanan) shared a photo of him with various culture and tourism officials, the temple acting as backdrop to the batik shirts and beaming smiles.

A tweet from the official Borobudur Twitter account showed Obama with local culture and tourism officials. Image: @BorobudurPark

These carefully managed – and extensively photographed – visits send messages to the viewing public about Indonesia’s ancient past and its legitimacy, now, as a world-class tourist destination. The ubiquity of social media in Indonesia has only added to the visibility of these visits on the world stage.

Since Borobudur and nearby Prambanan were recognised as UNESCO World Heritage sites in 1991, domestic and foreign visitor numbers have been steadily increasing. Borobudur currently attracts around 360,000 foreign tourists per year, and officials have expressed hopes that Obama’s visit will result in these numbers rising to 400,000 by year’s end.

While UNESCO inscription boosts the profile of heritage sites, it can also be a poisoned chalice. It brings with it more formal reporting requirements and greater expectations about management and conservation, with funds directed towards World Heritage sites often coming at the expense of other heritage sites. In the cultural landscape around Borobudur, local communities have experienced the disruption of expanded tourist infrastructure. For many, this has meant a shift away from agriculture and towards tourism as a revenue source.

Setting aside the fact that his visit to Borobudur was accompanied by 650 security personnel, Obama’s visit also conveys the message that Indonesia is safe for international visitors. Despite a bombing in 1985, and recent security threats made against the temples, media photographs showed a relaxed family on holiday. A Yogyakarta-based tourism official remarked,

Obama’s visit will further strengthen the safe image of Yogyakarta as a leading tourist destination… following the visit of Obama and his family, the number of foreign tourists from Europe, the US, and Asia to Yogyakarta would increase.

Obama waves to visitors at Prambanan temple on 29 June 2017. Image: Reuters/Pius Erlangga

The afterlives of monuments

While their significance has changed over time, these temples have never been neutral: they have extended Dutch colonial power into the cultural realm, legitimised independent Indonesia as a nation-state with its own heritage, and, post- UNESCO inscription, allowed the temples to grow as a tourism resource. Onto these sites, individuals and groups have projected spiritual, historical, nationalistic and political imaginings – and will continue to do so.

Deborah Cherry, Professor of Art History at the University of the Arts London, believes that monuments have afterlives – they can be re-modelled, re-used, re-sited, re-made, cast aside, destroyed or abandoned to accommodate changing political and social climates. Although Obama expressed an interest in the ongoing restoration of Prambanan, it was the symbolic value of these temples, as emblems of pluralism and religious tolerance, that he dwelled on:

I saw Borobudur Temple, a Buddhist temple in a [predominantly] Muslim country, Prambanan Temple, a Hindu temple that is being preserved in a [predominantly] Muslim country, as well as a traditional shadow puppet play and the Ramayana story. Tolerance should be the spirit of Indonesia, and it is also reflected in church and mosque buildings that are located right next to each other.

He also reiterated the importance of protecting and preserving the temples because, as he told Indonesian President Joko Widodo, ‘I believe in the future of this country.’

A future that is still, it seems, embedded in the past.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss