In my very-shortly-to-be-published book, Thailand’s Political Peasants, I argue that a distinctive relationship has emerged between Thailand’s rural population (which I describe as a “middle-income peasantry”) and the Thai state. This relationship is characterised by a combination of (1) relatively low agricultural productivity and (2) heavy dependence on state subsidy. This has produced a rural population for which a strong electoral relationship with the state is of central socio-economic importance.

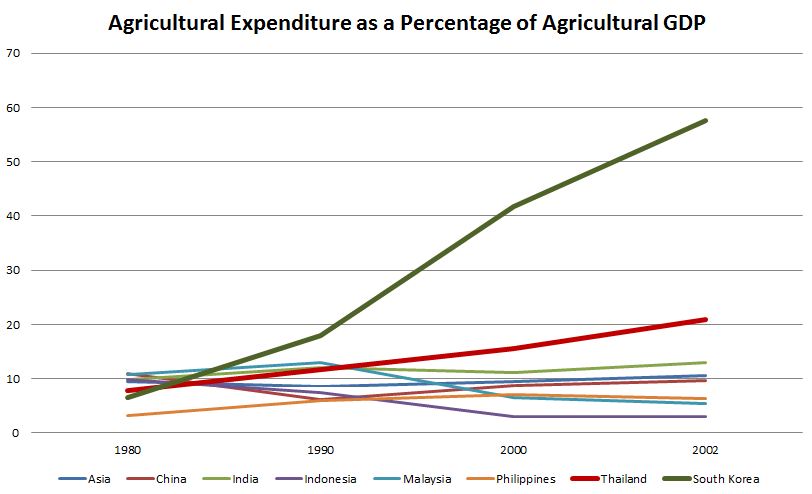

I recently came across some comparative data on agricultural expenditure that illustrates one dimension of this argument (Table 2.4 in this paper). Some of the data are summarised in the graph below. It shows government agricultural expenditure as a percentage of agricultural GDP in a number of different Asian countries from 1980 to 2002 (and it includes the Asia average). Thailand is a strong performer on state investment in agriculture. There was a solid jump between 2000 and 2002 with the arrival of Thaksin, but the upward trajectory long pre-dates the Thaksin era.

Thailand is a big spender on agriculture but, as I have argued in some earlier posts, this has not had a dramatic effect on agricultural productivity. Thailand’s middle-income peasantry is locked into a relatively unproductive relationship with the state.

However, in terms of government investment in agriculture, Thailand is far from being the stand-out in Asia. In the following graph, I have added the data for South Korea. The contrast is striking. (Unfortunately data for Japan is not provided.) In 2002 the government’s spending on agricultural equalled almost 60% of agricultural GDP. Importantly, government action in Korea really has transformed the agricultural sector. In the context of a dramatic movement of labour out of agriculture into other sectors of the economy, agricultural productivity in Korea has climbed dramatically. I will explore this issue in more detail in a later post.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss