After a six month run (24 June 2017 – 7 January 2018), ‘Passion + Procession: Art of the Philippines’ is just about to close at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW). Before it does, however, the members of Perspectives on the Past decided to conduct a little experiment: to visit this exhibition, and to each write a mini-review based on our own insights, experiences and knowledge. This was no small challenge, as our disciplinary backgrounds are diverse – archaeology, performance studies, museum and heritage studies, and history – and our perspectives even more so.

***

First, there’s the title, ‘Passion + Procession: Art of the Philippines’, in colourful letters on a simple white wall leading into AGNSW’s Upper Asian Gallery. I am sure some curatorial staff are quietly thrilled with how the exhibition’s alliterative name manages to introduce the key themes of ritual and politics (or, as my friend wryly observes, ‘Jesus and Guns’). But it’s the subtle use of + instead of and that catches my attention: is this a cross for crucifixion, or a target for practice?

Entrance to ‘Passion + Procession: Art of the Philippines’, AGNSW. Image: Natali Pearson

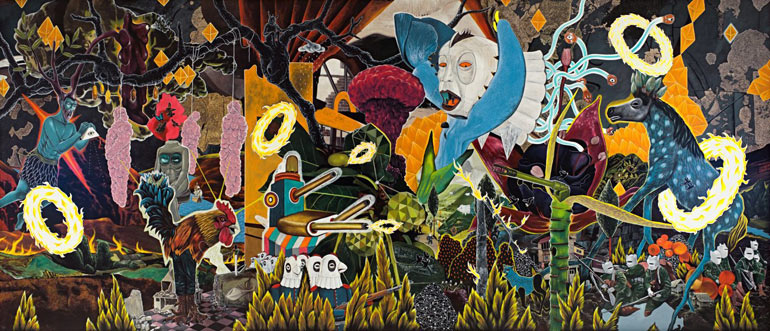

In contrast to this simplicity and subtlety, the first work of art I see is an oversized riot of colour – Rodel Tapaya’s Do you have a rooster, Pedro? (Adda manok mo, Pedro?) (2015-16). This is a grand statement – not just of the artist’s, but also the exhibition’s, intent. It is surreal, chaotic and violent, and rewards longer viewing. There are pink, cocooned bodies hanging from a charred tree, armed soldiers with bird heads, and spinning rings of fire. I usually prefer to find my way into a work of art without the help of curatorial text, but in this case I am grateful for the adjacent wall panel, which tells me that the eponymous rooster has been made flightless as punishment for his violence and unruliness. Tapaya has used the rooster as a symbol of control, violence and betrayal, and as a way of highlighting disrupted peace negotiations in the southern Philippines’ Mindanao region.

Rodel Tapaya, Do you have a rooster, Pedro? (Adda Manok Mo, Pedro?), 2015-16. Acrylic on canvas. AGNSW.

Curiously, according to the text, the rooster also relates to the story of Jesus predicting that Saint Peter (San Pedro) would deny him three times before a rooster crowed the next morning. Regular gallery-goers might recognise a neat synchronicity here, because – be it by accident or design – this is a story that is also being told in the major exhibition gallery downstairs, where Rembrandt’s Denial of St Peter (1660) is on display as part of the ‘Rembrandt and the Dutch Golden Age’ exhibition.

Rembrandt van Rijn, The Denial of St Peter, 1660. Oil on canvas, 154 × 169cm. Rijksmuseum.

As we move further into the exhibition space, my friends talk and dart about, dipping into works of art and peeking around corners to get a feel for the space. Curators and exhibition design staff spend a lot of time planning and executing an exhibition, but visitors – like my friends are doing now – can miss the wayfinding clues. Sometimes this is a deliberate choice on the part of the visitors, like one of those Choose Your Own Adventure books– subvert the curatorial intention and you might get a different outcome.

Wayfinding: Gallery guide (what you are supposed to do), AGNSW. Image: Natali Pearson

In their enthusiasm, visitors can also miss the gallery’s clues about where not to go. As they peer deep into a painting, my friends accidentally step over the black lines on the floor (“do not cross”). Wondering about the carving technique used to create the wooden sculptures scattered throughout the gallery space, one of us gets too close, and the security guard quickly makes his presence felt. The wood looks smooth and I long to run my hand over it, but this would probably have us ejected.

Too close? Rodel Tapaya, Do you have a rooster, Pedro? (Adda Manok Mo, Pedro?), detail, 2015-16. Acrylic on canvas. AGNSW. Image: Natali Pearson

Renato Habulan, Pilgrimage (Lakbay panata), detail, 2012. Wood, wax and found objects. On loan from Mr Edwin V Valencia. Image: Natali Pearson

There are ten contemporary Filipino artists featured in this exhibition. For me, there are two stand-out pieces. The first is the glorious The bond is stronger in the age of division (2017) by Geraldine Javier, consisting of dozens of plants rendered in embroidery and enclosed in wooden frames. Each embroidery/plant is connected to those around it by looping strands of silk thread – a root system that seems to spread across the wall and join the entire work together.

Geraldine Javier, The bond is stronger in the age of division, 2017. Wood, silk and cotton thread, silk organza, synthetic yarn, embroidery. Courtesy of the artist and A3. Image: Natali Pearson

Geraldine Javier, The bond is stronger in the age of division, detail, 2017. Wood, silk and cotton thread, silk organza, synthetic yarn, embroidery. Courtesy of the artist and A3. Image: Natali Pearson

Instead of a curatorial statement, this piece is accompanied by text written by the artist herself:

My appreciation for plants is always focused on the leaves and flowers, but never the roots. However, as an avid gardener, I know how vital roots are to a plant’s growth. They are hidden from sight and often ignored. Maybe that is a bit like how we view people. We judge them too by outward appearance – or gender, religion, nationality, even by status in life. What is hidden, like the roots of the plants, is a deeper psyche, or collective unconscious that connects us all. A connectivity that can’t be cut off by poor signals or power interruption.

But how do roots move through the earth? Do they respond to situations, crisis, like we do? Do they invade and kill neighbouring roots? Do they reach out and tangle with each other for added strength and even, perhaps, create a sense of community?

This work reminds me of Southeast Asia’s botanical resources – of how plants and their by-products were used as dyes, as medicines, as food enhancers, and of the critical role they played in fostering global maritime trading networks. It reminds me of explorers and colonisers, of how places – and people – were valued for their economic and scientific potential and sometimes little more. It also seems to be a visitor favourite – during my hour in this gallery, I witness no fewer than three different groups pose for photos in front of this work.

Posing at the gallery. Image: Natali Pearson

The other work that catches my attention – in fact consisting of three separate pieces – is that of Norberto “Peewee” Roldan. In There are no ideas but in things: 100 perfumes, clusters of glass perfume bottles are assembled on an old dressing table, a bright lighting fixture bringing their decorative lids into relief. Each perfume has been used, some more than others. Are they someone’s favourites?

Norberto Roldan, (L) There are no ideas but in things: 100 perfumes, detail, 2005. Installation with cabinet, mirror with collage, found bottles and lighting fixture. On loan from Paulino and Hetty Que. Image: Natali Pearson

Above the table hangs a mirror, paint flaking off its wooden frame; its lower edges are crowded with a handful of postcards, pages torn from a calendar, a wedding photo. There are political overtones in this collection of papers, but (unlike the transparency of the glass bottles) their meaning remains opaque to the uninitiated. This is a domestic altar of a sort, a shrine to female grooming and beauty that, like the light behind those glass bottles, is brought into stark relief through its proximity to the more overtly- religious ornaments on display in the other two altars (There are no ideas but in things: first communion and There are no ideas but in things: 10 hail Mary’s).

Norberto Roldan, (L) There are no ideas but in things: 100 perfumes, detail, 2005. Installation with cabinet, mirror with collage, found bottles and lighting fixture. On loan from Paulino and Hetty Que. Image: Natali Pearson

These assemblages bring together the personal and the communal, representing, as Roldan says, ‘a parallel world – the past and the present – where we may assign our own arbitrary memories and from the predicament of our own self-imagined symbols, we can attempt to assemble a sense of order and truth.’

Norberto Roldan, (L) There are no ideas but in things: 100 perfumes, 2005. Installation with cabinet, mirror with collage, found bottles and lighting fixture. On loan from Paulino and Hetty Que. (C) There are no ideas but in things: first communion, 2005. Installation with cabinet altar, picture frame, found objects and lighting fixture. On loan from Lito and Kim Camacho. (R) There are no ideas but in things: 10 hail Mary’s, 2005. Installation with box altar, plastic dayglo figurines, found objects and lighting fixture. Courtesy the artist and Silverlens. Image: Natali Pearson

I saw some of Roldan͛s altars in Manila recently, where I also attended the Asia Society Arts and Museum Summit. Roldan had participated in a panel on local identity in a global context (moderated by Mikala Tai from 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art), and had shocked conference attendees with his announcement that Green Papaya Art Projects, the artist-run initiative he co-founded in 2000, was closing. For a long time, Green Papaya has been held up as an example of how small cultural organisations can thrive outside major institutions, but this model, says Roldan, is no longer viable. Rather than just shutting shop, Roldan is, with the assistance of Asia Art Archive, carefully and deliberately curating Green Papaya’s own death. It takes courage and vision to accept when a project, especially a long-running and widely- lauded one, is over, and I like Roldan’s work all the more for the difficult decisions he has made with Green Papaya.

As AGNSW expands its institutional authority (and footprint) with the Sydney Modern Project, I can only hope that there are more exhibitions like this – showcasing the diversity of artistic practice in both Australia and our region, and providing a space for discussions about, and close engagement with, religion, politics, gender and other issues both global and local. Rembrandt is not the only one who has something to say about San Pedro and the rooster, after all.

Rodel Tapaya, Do you have a rooster, Pedro? (Adda Manok Mo, Pedro?), detail, 2015-16, acrylic on canvas. AGNSW.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss