Should we recognise humanity in another species? Robert Cribb takes a look.

In the 21st century, a growing campaign in the West has argued that orangutans and other great apes should be given qualified ‘non-human’ rights.

The campaign focuses on protecting great apes from being held in captivity (in zoos and circuses) and from being used in medical experiments. This call is for rights going beyond humane treatment for all animals and beyond the protection of great apes in the name of conservation.

Instead, it argues that the close neurological similarities between humans and great apes (and sometimes a few other animal groups such as dolphins, elephants and parrots) mean that these animals need to be treated with special consideration. In the case of orangutans, the argument rests on impressive evidence that they have complex social relations and are even able to feel compassion for other animals.

Fascination with the similarity between humans and orangutans goes back more than three centuries. Scientists, philosophers, theologians and creative writers have juggled with just how much importance to attach to anatomy, intelligence and culture in deciding where to place the orangutan in the human family.

In early travellers’ tales, it can be difficult to distinguish between stories of orangutans and stories of exotic human communities. Scattered through the travel literature are accounts of orangutans who hunted elephants, made fire, cooked meals, built simple huts and buried their dead.

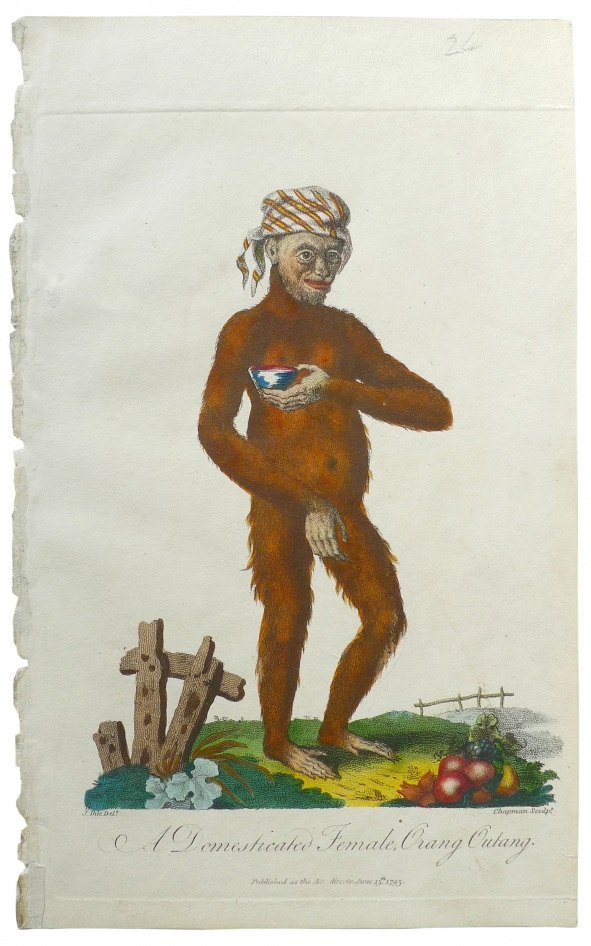

Most of the orangutans to reach the West during the 18th and early 19th centuries, however, were infants, taken from their mothers in Sumatra and Borneo and shipped to Europe as pets. The Dutch Stadholder Willem had one; Napoleon’s wife, the Empress Josephine had another.

Few of them survived even a single European winter, but while they lived, they captivated their owners and broader publics with cute behaviour. They would wear clothes, eat in a genteel way in imitation of humans, and show a child-like affection for their carers.

These observations, along with the travellers’ tales inspired the French philosopher Rousseau to conclude that orangutans were indeed humans whose evident lack of development was due to their isolation in remote jungles. He and other philosophers of the day were fascinated by so-called ‘wild children’ who had grown up in forests away from human company and who had the physical from of humans but none of their social characteristics. The name given to such people, homme sauvage (‘man of the forest’) was an exact equivalent to orang utan (Malay, ‘man of the forest’) and the Dutch ‘bosjesman’, which was applied to the indigenous peoples of southern Africa.

This early recognition of orangutans as humans crumpled in the face of three developments. First, specialists in the new discipline of anatomy began to demonstrate that the physiological differences between orangutans and humans were significant. Second, growing Western knowledge of other parts of the world pushed the early stories of ‘advanced’ orangutans into the realm of myth. And there was a sharp attack on orangutan status in the name of human rights.

Although Rousseau is hardly to blame, his idea of orangutan human-ness were taken up by the proponents of slavery. Recognising orangutans as human made it easier to argue that there was a hierarchy of humankind, stretching from orangutans at the bottom through indigenous Australian and southern African peoples, then Africans, then Asians, all the way up to Europeans.

The advocates of slavery even recalled a story that orangutans could speak but chose not to do so in order to avoid being enslaved. They argued that hard work was a characteristic of civilisation and that in this way slavery worked to ennoble primitive peoples who would otherwise be trapped in ape-like indolence.

In these circumstances, the advocates of human equality argued vehemently that orangutans should not be considered human. They emphasised the wretchedness of orangutan life in the jungle and stressed the unbounded savagery of great apes. The culmination of this portrayal was King Kong. Despite his filmic resemblance to a gorilla, his origin from an island off Sumatra makes him biogeographically an orangutan.

Ironically a similar concern with human rights underpins some of the modern-day resistance to recognising special rights for great apes. The argument is sharp: if we take the cognitive and emotional capacity of orangutans as definitive in giving them rights, there is a risk that we devalue the human rights of profoundly disabled humans.

The resemblance between humans and orangutans is discomforting and intriguing. The idea that we could reach across the species boundary and recognise humanity in another creature is both inspiring and repelling. Perhaps, however, the lack of respect that we show for Neanderthals, who are much closer to us than orangutans, suggests we should not expect too much.

Robert Cribb is Professor of Asian History at the Australian National University and, with Helen Gilbert and Helen Tiffin, author of ‘Wild man from Borneo: a cultural history of the orangutan‘ (University of Hawai‘i Press, 2014, soon to be released in paperback).

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss