I ought to have learnt by now not to make predictions about Indonesian politics, but I will say this: the present election certainly has the atmosphere of a walkover. Jokowi has been an articulate and focused campaigner, shamelessly exploiting the advantages of incumbency, and Ma’ruf Amin’s presence on his ticket has had the expected prophylactic effect against attacks on the president’s religious bona fides. Even if we allow for the possibility of some voters being deterred from picking Jokowi by a Jakarta-like scare campaign from grassroots religious leaders, a win for Prabowo Subianto still looks improbable.

Maybe because he can read the writing on the wall, Prabowo’s campaign has been a bit perfunctory. If his recent speeches and dozy debate performances are any guide, it doesn’t appear that he’s used the last five years to develop new rhetorical tactics to undermine undecided voters’ confidence in Jokowi. Indeed, his behaviour does little to weaken the thesis that Prabowo is running primarily to win parliamentary votes for his party, Gerindra, and thereby safeguard his influence on (or in) a re-elected Jokowi administration.

Given all this, most speculation about the future has less to do with the outcome of April’s election and more do to with what Jokowi’s second term might look like—and even which Indonesian politicians are best-placed to succeed him in 2024. This is why there’s an unusual level of interest in one of the vice-presidential candidates: Prabowo’s running mate, Sandiaga “Sandi” Uno.

Rich, telegenic, and relatively young, Sandi is the only person on his ticket doing the hard work of electioneering. In Sandi’s recent campaign trip to West Java, which included a day in Bandung on 10 March, we saw the signs of how this financier-turned-politician is using the 2019 campaign to build a political brand that’s independent of his association with Prabowo—and which, we can only assume, is designed to last him through a second Jokowi term.

This Gerindra cadre in Bandung was still gung-ho. (Photo: author)

• • • • • • • • •

Sandi Uno gained much of his national fame from being the running mate of Anies Baswedan in the 2017 Jakarta gubernatorial election, which was immediately recognised as a watershed for the mainstreaming of Islamic identity politics in Indonesia. Whereas Anies was a respected Muslim intellectual, Sandi entered the race without much religious credibility. I understand that he was counselled that he needed to make changes to his hitherto secular lifestyle if he wasn’t to be a liability for Anies’ campaign. Sandi soon adopted the veneer of piety now expected of Indonesian politicians, praying in public and inserting Islamic phrases and greetings into his public speech.

Although Sandi was a beneficiary of the religious-based campaign against Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (Ahok), he avoided the more odious rhetoric and alliances that Anies and Prabowo have pursued. Sandi, for instance, hasn’t been known to have met Islamic Defenders Front (FPI) leader Habib Rizieq Shihab or visit FPI’s headquarters, and he found excuses to not appear at either of the “212 reunion” events that commemorate the December 2016 anti-Ahok demonstrations.

But in 2019 Sandi finds himself again on the Islamists’ ticket of choice, and is obliged to pay obeisance to the conservative ulama who are campaigning on his and Prabowo’s behalf. Hence a curious get-together Sandi attended on Sunday at a home in Sindanglaya, a neighbourhood in the hills above Bandung.

The campaign schedule described it as an audience with “local figures” from West Java. These local figures were, in fact, a group of religious leaders who were closely involved in the 212 movement; apart from Sandi, the guest of honour was the former West Java governor Ahmad Heryawan, a star of the pro-Prabowo Islamist PKS party. Their host was Abu Syauqi, a businessman best known for founding Rumah Zakat, an Islamic charity. A Toyota Alphard and Mercedes S-Class rested in an open garage as testimony to Abu Syauqi’s prosperity, as mostly-female party cadres and volunteers mingled with their children while the ulama and politicians convened indoors. Their meeting was billed as a closed-door event, but audio was piped to speakers outside the house.

Members of Laskar Pembela Islam, an affiliate organisation of FPI (Photo: Quinton Temby)

A PKS supporter at the Sindanglaya event (Photo: Quinton Temby)

If there was ever a setting for Sandi to pose as a trusted friend of political Islam, it was here: in West Java, where conservative religious networks and their political influence run deep, and in the presence of some key organisers of the 212 movement which did so much to get him and Anies elected in 2017.

What was noteworthy about this meeting, though, was that Sandi didn’t engage in as much religious pandering as he might have. In interviews he has claimed that he thinks that the economy should be the singular focus of his and Prabowo’s campaign, and in the meeting at Abu Syauqi’s home, at least, Sandi stayed true to his word. He spoke to the ulama almost entirely about the economy, from the prices of staple goods to criticising a recent campaign promise from Jokowi to introduce a benefit for unemployed high school graduates.

Sandi still seems a little incongruous in company like this, his speech marked more by flashes of American-accented English than Arabic phrases. The only obvious invocation of Islam I noticed was his quoting a Qur’anic injunction against setting the community against itself, and even that was in the context of an appeal for those campaigning on his behalf to eschew “divisive” politics.

Still, whether or not the religious figures were expecting more red meat than they got, they allowed Sandi to leave with the endorsement he would have been looking for. The householder, Abu Syauqi, told journalists that “he’s now a vice-presidential candidate, one day president. I hope he becomes president. [He’s a] good guy”.

A vision of the future? (Photo: Quinton Temby)

• • • • • • • • •

If Sandi is going to be president one day, part of that story is going to be about his appealing to young Indonesians and their values. And the values that are ascendant among young Indonesian Muslims were on display at a campaign stop later that day, at a “Young Entrepreneur Summit” held on the campus of the elite Bandung Institute of Technology.

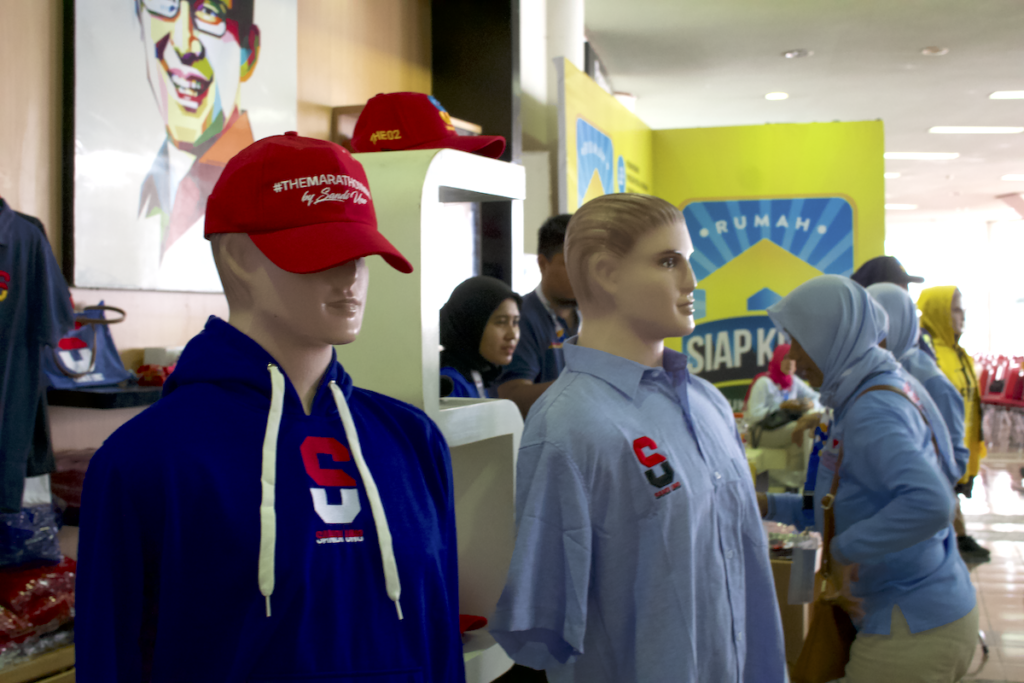

More than the Sindanglaya meeting, the Entrepreneurs Summit showed Sandi appealing to his natural constituency. The event was essentially a campaign event in the guise of a self-help extravaganza. The official Sandiaga Uno website, SandiUno.com, was a co-sponsor and media partner of event, and everybody in the 7,000-strong crowd got a show bag of Sandi Uno-branded merchandise.

If ticket-holders came for a show, they got their money’s worth. A DJ set and dance performance served as the warm-up act for Sandi’s keynote address on entrepreneurship, and a conversation featuring him and several famous Muslim entrepreneurs. Rossa, one of the superstars of Indonesian pop music, provided the closing entertainment.

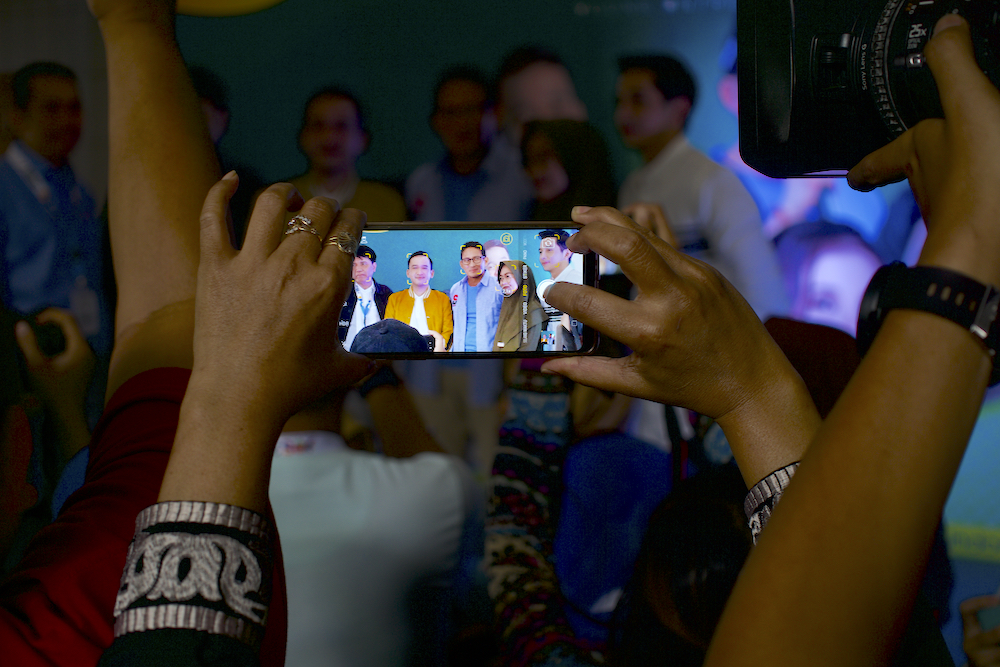

Selfies at the Young Entrepreneur Summit (Photo: author)

Sandi Uno merchandise at the Young Entrepreneur Summit (Photo: author)

More interesting, though, was the character of the attendees, and the obvious rapport between them and Sandi. They were were overwhelmingly young, and around two-thirds female, almost all wearing long jilbab. The event was organised by KAHMI, the alumni wing of a large Islamic students’ organisation, so the conservative flavour of the crowd was apropos.

Showcased here, perhaps, is an important element in Sandi’s present and future appeal: a successful Muslim businessman with an appropriate veneer of piety, speaking to the concerns of an expanding class of young Indonesians who are themselves modern, pious, and aspirational, yet as anxious as millennials everywhere about whether their education is opening up the sort of economic opportunities and social mobility they feel they deserve.

Opening prayers at the Young Entrepreneur Summit (this and above photo: author)

• • • • • • • • •

While Sandi is selling himself to voters as a successful yet relatable “entrepreneur”, the term means little except as a euphemism for what he really is: an oligarch. Sandi is typically referred to in the western media as a “billionaire” (which he does not deny), though we have no idea of his real net worth. If Globe Asia magazine’s estimate of a half-billion US dollar fortune is anywhere near correct, then that makes Sandiaga one of the wealthiest pribumi (i.e. non-Chinese) businessmen in Indonesia.

For scholars who advance the “oligarchy theory” of Indonesian politics, one thing that distinguishes the relatively small number of Muslim oligarchs from their ethnic Chinese counterparts is their ability to have a significant role in formal politics, unencumbered by the racism that limits ethnic Chinese elites’ participation in public life.

But the actual record of pribumi oligarchs in formal politics has been mixed, and particularly unimpressive in presidential politics. The likes of Aburizal Bakrie, Surya Paloh, and even Jusuf Kalla have had to settle for exercising behind-the-scenes influence on poorer but more popular politicians like Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono and Jokowi.

What makes Sandi Uno interesting among this set of Muslim oligarchs is that he may—and I stress may—have cracked the code, being rich enough to bankroll such of his own political activities as he chooses, and just likeable enough to have an electoral constituency substantial enough to become the basis of a viable presidential campaign.

“Time for the young to achieve” (Photo: Quinton Temby)

Press conference at the Young Entrepreneur Summit (Photo: author)

• • • • • • • • •

Having (or spending) lots of money isn’t enough to get you elected president, though. (Again, just ask Aburizal Bakrie). Whether Sandiaga Uno will be a leading candidate for the presidency five years from now depends on a few factors.

Ma’ruf Amin: Jokowi’s Islamic defender or deadweight?

Progressives may hope that Ma’ruf’s conservatism will be checked by realpolitik.

We might already be getting clues about what Sandi thinks the answer to those strategic questions are. He is doing what you might expect him to do if he has a post-election, post-Prabowo environment in mind: avoiding painting himself into a corner with on-the-nose appeals to identity politics, and not being too strident—and especially not too personal—in his criticism of Jokowi to risk burning his bridges with a president who, as Sandi would be well aware, has a vindictive streak.

And in Indonesia, nobody really wants to be in opposition if they can avoid it. Sandi was until recently a senior officeholder in Gerindra, which, if Jokowi wins, will most likely join his governing coalition for the sake of “national unity” and “reconciliation” in exchange for a few cabinet seats. If Sandi is inclined to stay in politics full-time after the election, that scenario might provide him with the perfect opportunity to insinuate himself into Jokowi’s orbit, and to maintain a public profile until it’s time to put together a presidential campaign.

Then again: what did I say about predictions?

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss