On Wednesday 4th of June, I attended an invitation-only fund-raising campaign for Jokowi-Kalla held at the Ritz-Carlton ballroom at Pacific Place. The event, Economic Platform Presentation of Jokowi-JK, was initiated by the Group of Professionals for Supporting Jokowi-JK. The group has been very successful in raising money for Jokowi-Kalla campaign. Up until Wednesday (4/6), they had reportedly raised Rp.25 billion for the PDI-P pair.

The event began with speeches delivered by invited speakers – Anwar Nasution, the chairman of Indonesia’s Supreme Auditing agency (BPK), Ari Soemarno, former CEO of Indonesia’s state-own energy giant Pertamina, infrastructure expert Ferdinand Nainggolan, and food security expert Florentinus Gregorius Winarno. The presentations were cut short by the MC, economist Rhenald Kasali. “Sorry but I am going to have to stop you there because Pak Jokowi needs to leave and we are all eager to hear from him.”

After a few rounds of polite interruptions by the MC, the warm-up gig was over and Jokowi finally walked onto the stage with the PDI-P campaign ad playing in the background. He began with the expected Islamic greeting and acknowledgements of VIPs in the audience. He described his running mate Jusuf Kalla as an “old friend”. Jokowi began his speech with a bold statement: the biggest problem Indonesia faces is not infrastructure or other issues highlighted by the previous speakers – it is attitude.

Jokowi showed a few slides containing graphs on the ever-increasing gap between the rich and the poor (to a wealthy audience) and argued that his government would prioritise on ensuring a more equitable distribution of wealth across the country. Wealth without the right attitude is worthless, he argued.

At this point I began to understand why some observers were concerned about Jokowi’s public speaking performance. He did not demonstrate the enthusiasm and energy that many people came to expect from a successful politician. Compared to Prabowo’s Sukarno-esque strongman oratorical performance, Jokowi was much more subdued and seemed somewhat hesitant from time to time. His relatively lacklustre performance as a public speaker became apparent when he deviated from his speech about the distribution of wealth – something that an experienced politician could use to incite passionate war cries from the audience – to his choice of attire. “I was heading to the car wearing my usual checkered shirt earlier, but my team asked me to put on a suit so here I am,” Jokowi explained, “and when I arrived here many people didn’t even recognise me.”

Jokowi’s expressed the need to develop human resources. He reiterated his statement about Indonesia’s attitude problem by arguing that elementary schools in Indonesia are placing too much emphasis on academic performance. Jokowi argued that in the status quo, elementary schools spend 80% of the time on teaching academic subjects, which leaves a meagre 20% on the more important aspects of education such as discipline, character and attitude building. “Now when you see elementary school students going to school, they always carry big backpacks full of books. To me that’s wrong,” Jokowi asserted. “I will make it 20% academic works and 80% character building.”

I was baffled by Jokowi’s portrayal of the problem of Indonesia’s primary education. Indonesia’s education is known to be plagued by a host of problems including the lack of well-trained teachers, systemic cheating, and the lack of a sufficiently robust academic teaching. None of the above can be described as an over-emphasis on academic education that not only overwhelms the students with pressure, but also cripples the development of students’ character. In fact, according to the latest results of OECD’s PISA tests, 95.7% of Indonesia’s 15 year-olds are happy in school, even though that they ranked at the bottom of the 65 countries in reading, math, and science. In light of this, Jokowi’s talks of cutting back on the teaching of science to make room for attitude building was oddly out of place with reality.

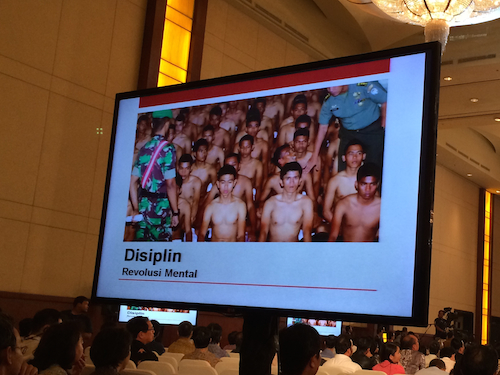

More baffling still was Jokowi’s attempt to link his education strategy to his argument about the need to develop human resources. Jokowi began with a powerpoint slide detailing his view on the ideal percentage of teachings on academic subjects and character building (Elementary 20-80, Junior High 60-40, Senior High 80-20). Then out of nowhere, the audience were doused in nationalism with a photograph of elementary school children participating in a flag raising ceremony with the caption pembentukan karakter (character building). This was followed by a photograph of a group of bare-chested soldiers at attention, with their duty officer at the front, presumably shouting instructions to their faces, captioned disiplin: revolusi mental (discipline: mental revolution).

All of the sudden I thought I was at Prabowo’s campaign fundraiser.

Eventually Jokowi brought us back from this out-of-place tour of militarism with a photograph of factory workers sporting pristine white uniforms, working side-by-side in some type of assembly line, captioned etos kerja (work ethics).

It was odd watching Jokowi presenting his interpretation of the relationship between education and workplaces. Indonesian elementary schools should devote 80% of the resources on building students’ character and discipline in order to make them patriotic and soldierly, so that they can become dehumanised cogs in megafactories as opposed to individual workers with attitude problems? I suspect he didn’t mean it quite like that, but his presentation did give that impression.

The theme of corporatism was further reinforced by Jokowi’s invocation of his entrepreneurial credentials and his plan to carry that to the Presidential Palace. “As a furniture salesman, I learned three lessons that I’ve been living by for the last 25 years,” Jokowi explained, “competitive pricing, product quality, and on-time delivery, that’s what business is all about.”

He explained that he plans to implement this philosophy on his management of the government bureaucracy. Jokowi did not shy away from reminding the audience his reputation as a man of action; he will set concrete objectives and actively monitor the progress through his trademark impromptu visit, blusukan. The government officials, including ministers, who fail to deliver results in a timely fashion will be fired. There are many other people who want to become ministers, Jokowi explained. It’s just like managing business.

Jokowi’s speech struck me as a bit poorly thought-out and difficult to follow at times. He portrayed the numerous challenges Indonesia is facing as a simple lack of political will. “Everybody knows that we need to cut fuel subsidy,” Jokowi claimed, “but why haven’t we done anything? Who knows? I will give you a present if you do,” joked Jokowi. “It’s a simple issue, but no one has the will to do it.”

He did not offer any insights about how he plans to mobilise the necessary political will. In his talk on energy issues, he lamented the frequent power outage, and in an almost Top Gear fashion, asked rhetorically: How hard can it be? It was obvious that Jokowi made these claims to try to convince the audience that the problems Indonesia is facing are political ones – or as he called them, an attitude problem. Thus as long as the next leader has the right attitude, all of the problems can be solved. This is perhaps why Jokowi is popular amongst ordinary working class Indonesians – that he is one of them, that one does not need to be an elite to tackle Indonesia’s problems. “I am a simple person; I am not smart,” Jokowi kept reminding the audience. This may very well be an effective strategy in a blusukan tour in Pasar Minggu. However, it’s uncertain if the approach holds the same appeal to a group of business elites in an opulent ballroom.

Instead of highlighting his experience as a political leader, Jokowi seemed more inclined to invoke his credential as a furniture entrepreneur. This was perhaps a conscious strategy given the nature of the event, yet throughout the speech, we barely heard anything about Jokowi’s experience as a political leader.

The point he made most enthusiastically with regards to his experience of holding public office was his well-known blusukan. He described it as his way of identifying the real problems and ensuring that things are done efficiently. He gave an example of how he ambushed a government office a second time a few weeks after his first visit, which received a round of applause.

I suspect the audience came fully prepared to hear Jokowi’s blusukan stories. However, since Jokowi is likely to have to give blusukan up as the President of Indonesia, it’s a pity that he did not highlight his other achievements in politics.

But of course, Jokowi was not without his charm. He was animated when he was making the case for an Indonesian drones programme. “The US drone command is in Nevada, they can monitor activities in Iran from there!” Jokowi seemed genuinely impressed and excited by this. He argued that the dual-use nature of drones makes is very cost-efficient and therefore suitable for dealing with both security threats and economic issues such as forest fire, illegal fishing and logging. “I am not going to tell you how much a drones programme would cost; trust me, it’s not that expensive,” he smiled mischievously. When he was speaking about the difficulties Indonesian farmers are facing, his emotion was believable. “You will cry if you see the fate of the farmers now,” Jokowi said to the audience, “it’s ok to have housing developments, but don’t take the fertile lands away from the farmers.”

Perhaps more surprisingly, he did not hold back in expressing his frustration with Indonesian bureaucracy. “Eeerrrr,” Jokowi vocalised in frustration when he was speaking about the difficulties of obtaining corporate licences. Online licensing is the way forward, Jokowi argued. “I am not smart, but I can call programmers to make me an e- online programme; there are many smart people in the younger generation who can help me do this.” This was a popular message to the young entrepreneurs sitting in the audience.

It’s perhaps due this combination of his candid display of opinions, his unpolished boyish charm, and the simple fact that he is Indonesia’s biggest star in politics, the audience gave him a standing ovation when he was finished.

This led to a somewhat awkward conclusion to the event: an exodus of people before Jusuf Kalla’s concluding speech. It was abundantly clear who everyone came to see.

………………………

Tzu-Chien, Yen (Ray) is an ANU alumnus living in Jakarta.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss