Observers of the Indonesian 2024 presidential race recently witnessed a surprising turn of events. After a period of relative silence on the matter, presidential hopeful Anies Baswedan finally declared his choice of running mate. To the astonishment of many, it was none other than Muhaimin Iskandar, the chairman of National Awakening Party (PKB), a member of the coalition of parties that had until that point supported Prabowo Subianto’s presidential bid.

The sudden political marriage of Anies and Muhaimin—brokered by Nasdem Party chairman Surya Paloh—sparked outrage within Anies’ own coalition. The Demokrat Party—whose chairman, Agus Harimurti Yudhoyono, had been seen as the strongest candidate for Anies’ running mate, immediately declared their departure from the coalition. Demokrat grassroot cadres expressed their dissatisfaction by dismantling party’s banners and campaign materials and deleting postings on social media featuring Anies. Even the Prosperous Justice Party (PKS), another member of Anies’ political coalition, was deliberately absent during the declaration of the Anies–Muhaimin ticket, as well as the first post-declaration coalition meeting, implying their dissatisfaction.

The rise of Muhaimin to the forefront of presidential race fuelled dissent not only among the competing coalition of parties, but also internally within Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), the Islamic mass organisation PKB is closely associated with. As the largest Muslim organisation in Indonesia, the votes of NU grassroots followers—or nahdliyin—have always been highly prized, and even considered a decisive factor in securing victory in presidential elections. Since Indonesia’s first direct presidential election in 2004, NU higher-ups like Hasyim Muzadi and Salahuddin Wahid have contested as vice presidential candidates. Most recently, Jokowi’s victory in the 2019 presidential election has widely been credited to the selection of Ma’ruf Amin, a senior NU kyai (religious scholar) as his running mate, which allowed him to reap the votes of nahdliyin.

However, the declaration of the Anies–Muhaimin ticket brought into light existing fissures within the nahdliyin community—over NU’s ideological orientation, its involvement in electoral politics and its relationship with PKB, and the role of Muhaimin within its political and religious milieu. In the absence of the distinctive political conditions that unified NU behind Jokowi and Ma’ruf Amin in 2019, the political role of NU and its followers in the 2024 elections will be the subject of intense contestation.

Muhaimin Iskandar campaigning after his appointment as Anies Baswedan’s running mate (Photo: Muhaimin Iskandar Facebook)

Factionalism and dissent within NU

Ideological concerns have been at the forefront of many objections to Muhaimin’s partnership with Anies. Ever since Anies successfully courted the support of hardline Muslim groups during his ascendancy to the governorship of Jakarta in 2017, he has had a conservative image which goes against the values of moderation, openness, and tolerance highly esteemed by nahdliyin.

As such, Anies’ partnership with Muhaimin—someone expected to epitomise and advocate NU values—has been seen as ideologically incompatible by some elements of the nahdliyin. This is not to mention that Anies is also supported by the conservative PKS—which, with its roots in the Muslim Brotherhood-inspired tarbiyah movement, is ideologically different to NU. Hence it is not surprising that there were many nahdliyin who hoped that PKS would exit Anies’ coalition after the declaration, as Muhaimin himself admitted in a recent interview.

These ideological concerns arise in the context of a continuing debate within NU communities about the organisation’s political role and its relationship with PKB. At the grassroots level, and especially on social media, tensions surrounding Muhaimin’s nomination have been reflected in a split between those who oppose the nomination on the grounds of maintaining the “neutrality” of NU as a social organisation and those who believe that the political identity of PKB is inseparable from NU’s socio-ideological milieu.

These tensions surfaced immediately after kyai Yahya Cholil Staquf, the chairman of the executive leadership board of NU at the national level (PBNU), publicly warned any presidential candidate not to drag the organisation into pragmatic politics. Coming just days after the announcement of the Anies–Muhaimin ticket, Yahya’s statement was undoubtedly directed at the PKB chairman.

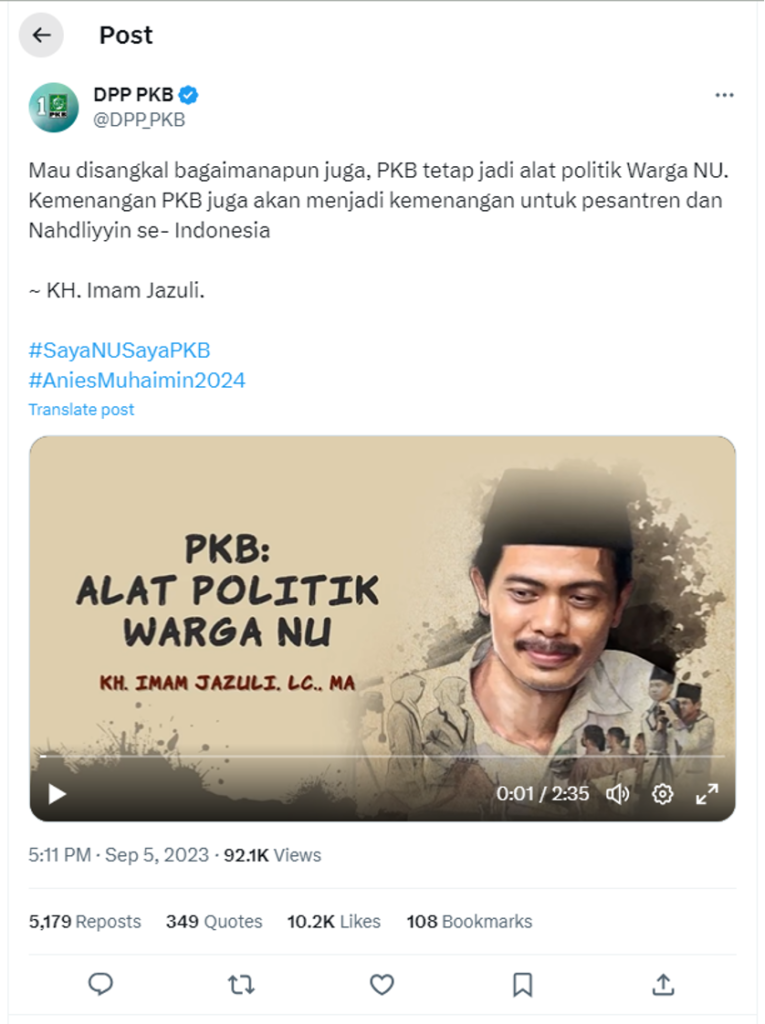

Responding to this public warning from Yahya, many pro-Muhaminin NU cadre and PKB members took to social media. The hashtag #SayaNUSayaPKB (“I am NU therefore I am PKB”) has been widely posted and tweeted to show that NU and PKB are essentially inseparable. Among the proponents of this movement is the young and influential kyai Imam Jazuli, as posted on PKB’s official Twitter channel.

PKB’s official Tweet on the inseparability of NU and PKB, citing kyai Imam Jazuli’s statement

This grassroots discord is essentially rooted in elite-level factionalism. At its heart is the political rivalry between three main NU factions: Muhaimin’s camp; the “Rembang” establishment; and the loyalists of Abdurrahman Wahid (affectionately called “Gus Dur”), the former Indonesian president and one of the founders of PKB. The Rembang establishment encompasses the PBNU chairman Yahya, and his younger brother, Minister for Religious Affairs Yaqut Cholil Qoumas, along with other kyai and NU functionaries under their patronage. These two names hail from a well-respected line of NU figures and pesantren establishments with roots in Rembang, Central Java.

Minister for Religious Affairs Yaqut Cholil Qoumas (left) and his elder brother, PBNU Chairman Yahya Cholil Staquf, speak to the media after a meeting with President Joko Widodo, March 2023 (Photo: Setkab RI Facebook)

Not surprisingly, soon after the Anies–Muhaimin declaration and the pair’s public appearances in the media, Minister Yaqut gave a statement that went further than his elder brother’s, appealing for voters not to endorse a candidate who had created and taken advantage of socio-religious polarisation for political purposes. There is no doubt that this statement was directed at Anies, or that it was likely intended to further fan the flames of ideological tension between NU supporters and conservative elements, thus putting Muhaimin at a disadvantage.

The rivalry between Muhaimin’s group and the Rembang establishment revolves around the 2021 PBNU Muktamar, or congress, at which Yahya was elected chairman, defeating two-term incumbent Said Aqil Siroj, who is known to be very close to Muhaimin. The emergence of Yahya as the new Chairman meant the reduction—if not the outright disappearance—of Muhaimin’s political clout in PBNU.

Nahdlatul Ulama and the politics trap

A pillar of Indonesian civil society faces an ever more acute dilemma between representing a religious community and securing resources and influence within government.

Meanwhile, tension between Muhaimin’s camp and the sympathisers of former president Abdurrahman Wahid, or Gus Dur, stems from the unresolved quarrel over the transition of PKB’s leadership from Gus Dur’s camp to Muhaimin circa 2008, when both sides claimed rightful leadership over the party. Muhaimin emerged as the victor in the legal battles that ensued, gaining official command over the party organisation.

It is no secret that Gus Dur’s family and loyalists still hold a grudge against Muhaimin. This resurfaced publicly after Muhaimin stated in a television interview that he did not mastermind a coup against Gus Dur, but rather that he was the victim of the coup. His statement immediately invited derision from the ex-president’s daughters. Allisa Wahid accused Muhaimin of spreading false information and demanded that he apologise and not use Gus Dur in any way for his own political gain. Meanwhile, Yenny Wahid— whose name has been circulating in polls as potential vice-presidential candidates—has also repeatedly questioned Muhaimin’s loyalty, decency, and moral character, especially in light of his history of conflict with Gus Dur.

Allisa Wahid’s tweet criticising Muhaimin

Tough race in East Java’s electoral battleground

With attacks coming at Muhaimin from all sides, and factionalism and elite rivalries plaguing the NU establishment, the PKB chairman is facing a situation that is fundamentally different to the 2019 election, when NU unequivocally threw its support behind one man, Ma’ruf Amin, as Jokowi’s running mate.

The condition that facilitated a greater unity within NU back then—the existence of an external threat of conservative Islamic elements—is no longer present today due to the relative success of Jokowi’s systematic, albeit draconian, antiradicalism policy. Muhaimin’s hopes seem to rest on consolidating the support of grassroots NU santri (students of pesantren) and sympathisers through the patronage of local kyai.

Fortunately for Muhaimin, he still commands a great deal of support from charismatic NU leaders who are enthusiastic about his candidacy. Other than the so-called “Cirebon clique”, which includes Said Aqil Siroj and Imam Jazuli, Muhaimin can expect support for his candidacy from notable names in East Java. Chief among them would be kyai Kholil As’ad of Situbondo, whom Muhaimin has repeatedly claimed has given him a mandate to be Anies’ running mate. Former vice chairman of NU’s East Java provincial leadership board (PWNU), kyai Abdussalam Shohib of Jombang—who was recently abruptly dismissed from his position by Yahya’s PBNU—also stands ready to support Muhaimin, as do various other senior and junior kyai such as Abdurrahman Al Kautsar of Kediri.

It has been widely assumed that Anies’ choice of Muhaimin was underpinned by the logic of ameliorating his lacklustre polling performance in East Java. Indeed, East Java will be a central battleground in the upcoming 2024 election, just as in previous presidential elections, for its politico-cultural significance as a nahdliyin stronghold and because of the number of eligible voters there: more than 31 million, the second highest after West Java’s 35 million. Undoubtedly, Muhaimin’s support among kyai in East Java will prove crucial in tilting voters’ favour towards Anies’ camp.

However, it shall be noted that PKB did not score a sizeable majority over the votes in East Java in the 2019 election, obtaining around the same percentage of votes—about 19%—as PDI-P, now the political vehicle of Ganjar Pranowo. Partai Demokrat, which has been gravely disappointed by Anies’ choice of Muhaimin, still holds some influence in East Java and will not likely allow smooth sailing for Anies. Similarly, Prabowo Subianto’s coalition parties Gerindra and Golkar alone won a combined vote of 21% in East Java. When taking account of the disgruntled sympathisers of Gus Dur in the province as well, Anies and Muhaimin shall expect a very tough battle ahead.

Anies Baswedan at a PKS campaign event in Palembang, September 2023 (Photo: Anies Baswedan Facebook)

With the absence of an external threat to bind NU together, the key to winning the support of nahdliyin in East Java may lie in three areas. First and foremost, any candidate needs to possess in-depth knowledge of NU’s internal dynamics, subtleties, and context to be able to use the rivalries of different factions to his advantage. As shown above, internal frictions within NU are real, and might significantly tilt the balance of the 2024 election.

Second, winning over support in a tight electoral battleground as East Java requires significant investment of material resources as patronage since voters need bigger material incentives to be swayed. The race may be marked by what Edward Aspinall has called “patchwork politics”, where candidates fight long and hard over small plots of local constituencies (e.g. villages or pesantren) over time to win votes. The results of this strategy are often determined by the effective targeting of patronage to voters (and ensuring their reciprocity in the form of votes) through elaborate and systematic networks of brokerage. Local kyai and their networks, who possess granular insights into voters’ behaviour, often become influential players in such settings.

And finally, given that one cannot treat East Java as a homogenised political constituency, the support of other prominent NU figures in the region beyond the warring factions—such as the incumbent governor, Khofifah Indar Parawansa, or Mahfud MD, a senior minister in Jokowi’s administration—may prove crucial. It is widely agreed that Khofifah holds sway over the female cadre of NU in East Java, whereas Mahfud MD might hold the key to winning the votes of Madurese nadhliyin—who often exhibit different voting patterns than their mainland Java counterparts, as the previous elections have shown.

All in all, Anies and Muhaimin will face a rocky road ahead of the 2024 elections. The fact that they declared their ticket early provides an advantage to assess and deal with plausible obstacles before the official formal registration of candidates at the electoral commission. Yet, it also makes them vulnerable to countermoves and manoeuvrings by anyone wishing to tackle their candidacy.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss