The inaugural Salween Peace Park General Assembly was unlike any gathering that has occurred in Mutraw District, Karen State. From 3 to 5 April 2019, about 100 participants congregated in Day Bu Noh village for the event, including representatives of the district-level Karen National Union (KNU), leaders of Karen civil society organisations active in Mutraw, and two elected representatives from each of the 26 village tracts designated as part of the Peace Park area.

I have heard the General Assembly described as a “congress” or a “parliament”. In some ways it is: the assembly is a forum for discussion, dialogue, and negotiation among leaders that act in the interests of the area’s 38,000 inhabitants. Yet instead of statesmen, the General Assembly puts experienced leaders from the KNU and civil society into dialogue with community members who are being recognised as active participants in district-wide negotiations about peace, self-determination, and natural resource management for the first time. By creating a space for leaders and community members to converse on equal footing, the Salween Peace Park tests a new approach to peace in the heart of war-torn Kawthoolei—the “Karen homeland” claimed by the KNU.

I visited the Peace Park to witness the General Assembly as part of my PhD research on civil society, development, and governance in Karen areas. There are many aspects of the Peace Park that I do not feel equipped to write about—the indigenous ontology that guides its formation, for example, or its approach to natural resource governance, land issues, and wildlife conservation—even as these aspects are no less integral to the overall vision. Instead, I strive to map the Peace Park’s novel approach to governance and peacebuilding, a testament to my interest in how people relate to each another, and the profound changes that occur as a result.

District-level KNU leaders, civil society representatives, and community representatives gather for the three-day event, and are sworn in as part of the General Assembly. (Photo: author)

• • • • • • • •

Myanmar’s peace process appears to have exhausted its momentum. Words like “deadlock”, “stalemate”, and “stagnation” are common descriptors of the current state of affairs. Initiated by former president U Thein Sein in 2011, the peace process appeared successful in its early years, albeit superficially. In 2012, the KNU signed a bilateral ceasefire with the government, after 63 years of armed struggle; in 2015, eight ethnic armed organisations (EAOs), including the KNU, signed the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA), the first multilateral ceasefire in Myanmar’s history.

Yet subsequent years have sown doubt over these agreements. For one, the agreement hardly applies “nationwide”. Only ten EAOs are included in the NCA today; the agreement excludes significant EAOs like the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO), the Arakan Army (AA), and the Karenni National Progressive Party. Numbers of non-NCA-signatory fighters outnumber NCA-signatory fighters at least three to one. Among signatories, negotiations falter over critical issues such as de-mining procedures, demilitarisation, and security sector reform.

Tensions culminated on the third anniversary of the NCA in October 2018, when General Min Aung Hlaing reiterated the Tatmadaw’s uncompromising stance towards the peace negotiations, warning signatory EAOs against “misus[ing] the NCA” to “cause disintegration of the country”, and emphasising the Tatmadaw’s demands for the formation of a single army. Soon after, the KNU and the Restoration Council of Shan State—the strongest and most influential NCA signatories—announced a temporary withdrawal from the formal peace process. Their participation has not been reinstated.

The KNU’s withdrawal also reflects an internal rift between leaders more acquiescent towards the government of Myanmar (GoM) and leaders that hold a more uncompromising stance. The former faction has dominated KNU’s central leadership since internal elections in 2017 and is responsible for driving the KNU towards the NCA; the latter is sceptical of the NCA route and is associated with the northern districts within the KNU’s administration system. This includes Mutraw District, where the Salween Peace Park is located, and where most communities remain solely governed by the KNU.

Mutraw’s communities have become accustomed to war in the seventy years since the KNU initiated the Karen rebellion, and have continued to suffer armed conflict even after the NCA. Between February and April 2018, clashes in the area displaced 2,000 inhabitants. The displaced remain in Ei Tu Hta IDP camp, afraid to return despite ration cuts and service withdrawals. The Tatmadaw still operates 60 camps in the Mutraw area, connected by a roads that cut through numerous kaw, or locally-defined territories managed according to customary practices. The aforementioned clashes were provoked by further attempts at road construction between these Tatmadaw bases, in contravention of the NCA.

Persistent militarisation despite the NCA has aggravated doubts among Mutraw’s inhabitants about the central-level KNU’s ability to protect them from the Tatmadaw. The KNU’s October 2018 statement regarding its hiatus from the peace process appears to be a subtle recognition of the strained relationship between the central KNU and its war-weary northern inhabitants. The statement declares that the KNU seeks the “unified participation of the whole organisation,” presumably across its various factions and districts. What this means in practice—and how this will alter the manner in which the KNU pursues peace—remains unclear.

• • • • • • • •

Recent research emphasises the role of civil society and local communities in meaningful and sustainable peacebuilding efforts. Yet, as Rogert Mac Ginty laments, “local communities are almost never asked what constitutes peace and conflict to them”. Myanmar’s peace process likewise grinds on despite the dissatisfactions of civil society and local communities. More broadly, state–society relations in war-affected areas are becoming increasingly fraught. Issues relating to territorial control—I am thinking of hydropower and land legislation—imply that ceasefires invite a voracious appetite for natural resources, to the detriment of local communities.

These issues show that the peace process has not substantially challenged existing governance structures; rather, the process tacitly legitimises power imbalances between local communities and various authorities. Peace, refracted through the lens of Myanmar’s peace process, refers largely to high-level negotiation—a procedure that has not only been excruciatingly long-drawn, but also disembedded from communities that aspire to build peace for themselves.

It was in this context that the Karen communities of Mutraw declared the establishment of the Salween Peace Park, which covers 5,485km2 in Mutraw District, northern Kawthoolei, in December 2018. The Peace Park idea originated from discussions between KNU District leaders and Karen civil society leaders in the area, including the Karen Environmental and Social Action Network (KESAN), after the 2012 KNU ceasefire.

Between May 2016 and December 2017, a 47-member Peace Park interim committee—including the idea’s progenitors and community representatives—led a series of meetings with a total of 5,149 local inhabitants. Held across all 3 townships and 26 village tracts in the Peace Park area, meetings encouraged communities to identify the most adverse political, socio-cultural, and ecological effects of protracted conflict, and discuss the governance structures required to reverse them and build an equitable and long-lasting peace in the process. The Salween Peace Park Charter was crafted over these meetings, and then passed with the endorsement of 75.1% of the voting-age population (29,251 out of 38,968 signatures). The Charter was launched at the December 2018 event, and is now known locally as the Peace Park constitution.

By pursuing peace in the midst of militarisation and displacement, the Salween Peace Park circumvents national-level stalemates over security sector issues, while insisting that peace is more than the absence of war. Demilitarisation is deeply desired; indeed Article 63 of the Salween Peace Park Charter commits its people to pursue demilitarisation when it is strategically acceptable. But war’s effects reach far deeper than the tracks left by boots on the ground; it damages people’s sense of themselves within the wider world. The Peace Park Charter acknowledges the disempowering consequences of war and seeks to reverse them. Article 108, for instance, declares the inviolability of “the ecological and cultural integrity of land areas considered to be ancestral domain.” It therefore establishes, firstly, that war has eroded bio-cultural practices that are foundational to the worldview of indigenous Karen communities; and secondly, that peacebuilding must have both ecological and cultural dimensions. The Charter therefore implies that peace must be both multidimensional and locally-defined.

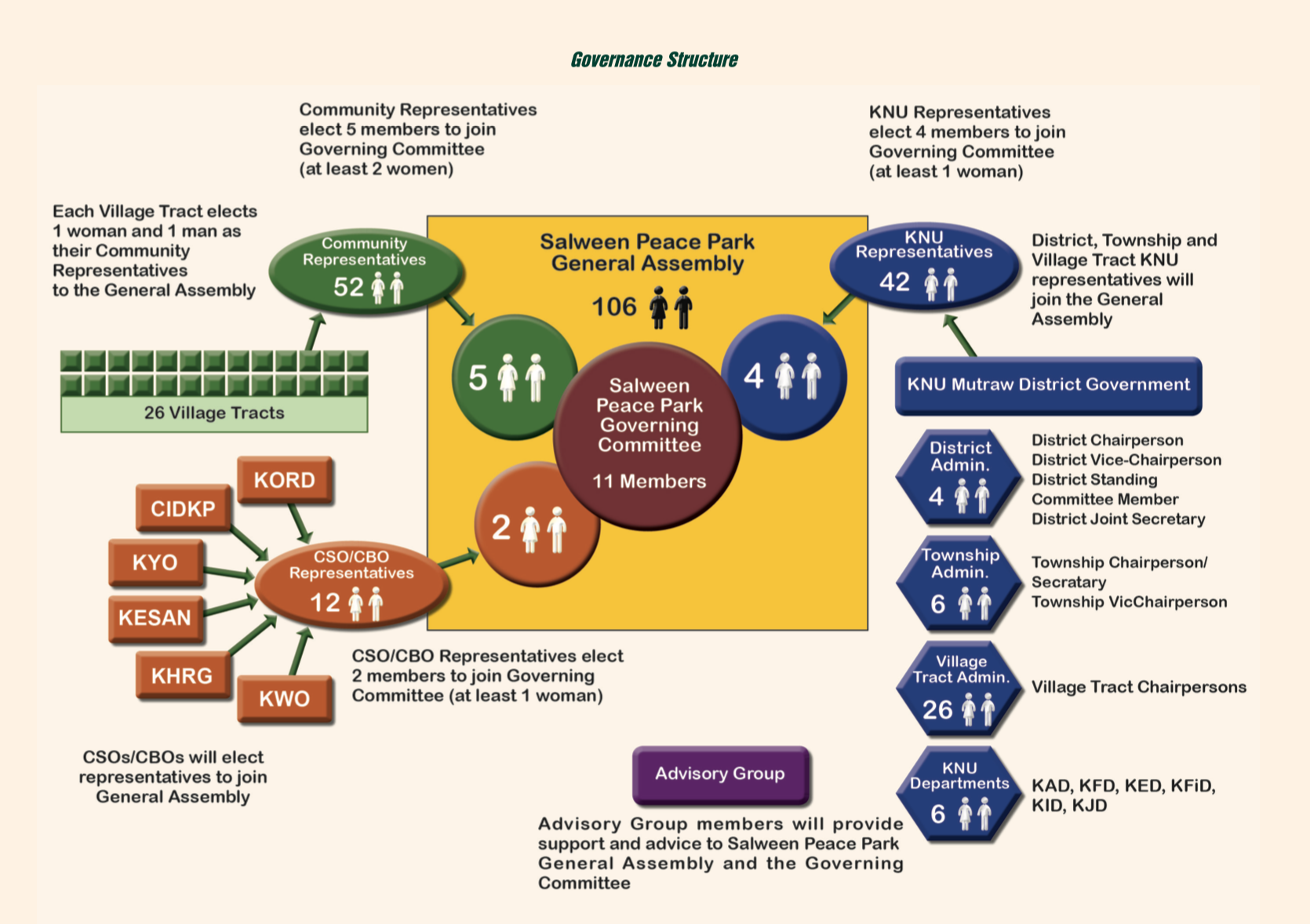

Moreover, the governance arrangements instituted in the Charter aim to reverse the highly unequal power relations, borne out of protracted conflict, between local communities and armed actors. Participatory mechanisms do not end with the Charter referendum mentioned above; instead inclusivity and self-determination are referenced throughout the Peace Park Charter. All its people shall have “equal right to and opportunity to participate in the governance, development, and improvement of the Salween Peace Park” (Article 11); and “legitimacy of governance shall be determined collectively… through a political process that is accessible, free of coercion and manipulation, transparent and not disproportionately influenced or unliterally determined by the KNU Mutraw District government or the Salween Peace Park Governing Committee” (Article 20). In practice, this has meant that the 52 community representatives in the Peace Park were elected through transparent elections at the village-tract level, independent of the KNU and civil society.

At the General Assembly, representatives established further obligations that strive for an equitable balance of power between communities and leaders. For instance, when community representatives are sworn in, they become responsible for communicating Peace Park-wide decisions to their village tracts, and obliged to represent their communities’ interests at subsequent General Assemblies. In contrast to the inequitable relationships between troops and civilians, and the armed and unarmed, these guidelines embolden local communities. Peace—in other words—demands not just demilitarisation, but a finely-tuned approach to cultivating just, life-affirming human relationships, even amid conflict.

The 11-member Salween Peace Park Governing Committee was voted in by the 106 members of the General Assembly on 3 April 2019 (Photo: author).

In most formal political settings, well-established leaders advancing their own peoples’ interests do so according to “seemingly universally accepted modes of rhetoric and behaviour.” Statesmen know how to greet each other, the manner in which to negotiate, the art of forming alliances and blocs. In contrast, the inaugural General Assembly was at times awkward, even uneasy. The meeting hall was divided into three sections, with designated seating areas for the KNU, civil society, and community representatives. On the first day, I watched KNU and civil society leaders greet each other with ease, whereas community representatives sat in silence.

Explaining the roots of KNU power struggles

The Karen National Union shows how internal conflicts in Myanmar’s insurgencies can complicate the peace process

Yet such discrepancies do not render the Salween Peace Park futile. Rather the opposite. Awkwardness, uncertainty, hesitation: these indicate the newness of the governance arrangements that the Peace Park brings to life. KNU and civil society leaders, in other words, were at ease with the decorum that formal meetings demand; community representatives were not yet privy to these unspoken rituals. And as the General Assembly enacts its roles and responsibilities, the dynamics between its members will change in unpredictable ways. Perhaps young men or women, now watching from the sidelines, will be future leaders—perhaps not. No one can foretell the outcomes of this governance arrangement, but this indeterminacy is precisely the point. In an area where conflict is the norm, something new is desperately necessary.

Community representatives review the Peace Park Charter (Photo: author).

• • • • • • • •

Still, indeterminacy implies the risk of failure. The most blatant threat to the Salween Peace Park is the Tatmadaw, whose provocations have not exhausted communities’ tenacious hopes for peace. Other threats include the Peace Park’s economic viability, co-option by community elites, that the momentum achieved over the last three years could peter out, or that the Peace Park might not receive the international recognition required to sustain it. Even where the General Assembly works to allay these uncertainties, their influence on Myanmar’s faltering peace process, amid the vagaries of international funding, remains limited.

However, taking a wider conception of peace, rooted in the texture of relationships between local actors, reveals that fixating on the “success” of the Peace Park misses the point. In years to come, the Peace Park itself may be remembered as little more than a romantic experiment in indigenous governance, but it will have created a space for relationships between community members, local authorities, and civil society actors that was previously unthinkable. Success or not, this constitutes a bold challenge to thinly conceived, top-down approaches to peace at national and international levels.

The four years since the NCA have proven top-down definitions of peace incongruent with bottom-up aspirations for cultural survival and self-determination. Moreover, continued threats of militarisation and displacement lend credence to the argument that peace donors should reconsider their support for the formal peace process, or at least nudge peacebuilding efforts away from an overreliance on the NCA.

Indeed, the dangers of conflating peacebuilding with state-building are well-documented, and the Peace Park provides a poignant corrective in Myanmar, where initiatives that claim not only to build peace, but also to transform governance arrangements themselves, remain sparse. In areas where the GoM has a strong presence, the space for communities to assert themselves remains constrained, despite an increase in civil society organisations in recent years. In Mutraw District, the Salween Peace Park, with the buy-in of the district-level KNU, shows that peacebuilding can be a bottom-up endeavour, and challenges donors to consider how peacebuilding initiatives might reach for wider, deeper, and more holistic societal transformations, rather than the mere avoidance of conflict.

I left Mutraw moved by the resilience of its inhabitants. On its misty mornings, I wrote field-notes to the sound of the river:“You feel it deeply: the serenity of the place, the spectacular forested landscapes, even the mystical power of nature. And then you realise: the Burma Army has sent columns through here. It is a war zone… You grapple with the depth of state-building and violence, that it should reach into a place like this.” The Salween Peace Park is a bold move towards self-determination in the midst of conflict, yet the source of its potency rests in the quiet strength of its elected representatives who traverse mountains and muddy paths to turn vision into reality.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss