Editor’s note: this is the second in a series of posts we’re bringing you this week that feature the views of young writers from President Rodrigo Duterte’s home region of Mindanao on two years of Dutertismo. Previously, lawyer Abdel Jamal Disangcopan reflected on what it means to witness Duterte’s presidency from the perspective of a Mindanaoan who previously admired aspects of Duterte’s local leadership.

1.

It is easy to make fun of Rodrigo Duterte. He will set up the joke for us, and all we have to do is to deliver the punchline.

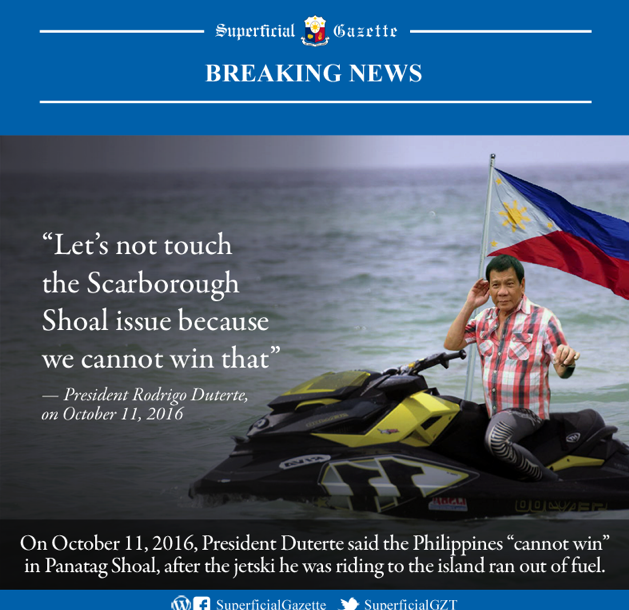

Imagine a plaid-donning septuagenarian riding a jet ski and confronting Chinese warships, for instance. It is a farcical idea—one that the Superficial Gazette of the Philippines, a parody Facebook account of the Official Gazette of the Philippines, has taken to its comical extremes through a meme.

It was an easy joke to make. Duterte made that exact promise on live television, in a five-way presidential debate, in what was then a tightly contested race.

Answering a question from a fisherman in the audience on how he could help Filipino fisherfolk to fish safely in the West Philippine Sea, Duterte said that he would jet ski to the disputed maritime territory and plant the Philippine flag there to assert the country’s sovereignty.

It had always been his dream to be a hero, he added. If he died there, Filipinos could cry for all they wanted.

Two years into his presidency, Duterte has been accused of being too soft on China. Duterte admitted that he “needs” China to support his administration’s projects. He said that China wouldn’t allow his ouster, much to his reassurance. For Duterte, confronting China only means “trouble.” Duterte even offered China a 60-40 joint venture in the West Philippine Sea.

When pressured about his jet ski promise, the President of the Republic said that he had just been kidding, downgrading the metaphorical “foreign policy” to one of his corniest jokes. He admitted the absurdity of it all, and delivered a punch line rebutting the jet ski meme: What would he do if he ran out of fuel? There are no petrol stations there.

The power of political jokes lies not just in its humour. In the Philippines, political jokes take power.

Here lies the paradox of making fun of Duterte. It is easy to make fun of him because his words are laughable. But what makes it easy is also the same reason why delivering a joke critical of the President is difficult.

By showing the ludicrousness of Duterte’s promise, the jet ski meme challenges Duterte to think of proper and diplomatic ways to uphold the country’s maritime claims. But Duterte’s dismissal of his own promise as a mere joke deflects such criticism. In effect, he is saying that the real problem here is that we have no sense of humour, that we are taking his words too seriously.

After all, we cannot blame a clown for being silly; he is supposed to be that way. To ridicule Duterte is redundant. Jokes against him, which have the potential to undermine his authority, are virtually pointless.

Internalise all this for a moment, and we will find ourselves desperately teetering on that very thin line between comedy and tragedy. It is no wonder that when we laugh at a joke, we sometimes wince a little.

2.

Mix humor and irony, exaggeration and pun, and shaming and political commentary. The outcome is satire.

Throughout history—from Aristophanes’ plays at ancient Greek theatres to memes on social media—satire has helped draw our attention to oppression and injustice, as well as the taken-for-granted ways in which power is abused. Every time we poke fun at Duterte, we hope to expose his hypocrisy, shame his savagery, and expect that others don’t just laugh with us, but also shake their heads and demand better.

This is rarely the case, however. Many of us have lost count of the friends who not only showed dismay at our jokes, but also rebutted them.

There is a meme of Duterte’s face superimposed on the wooden figure of the Santo Niño. It satirises Duterte’s messianic appeal to his most devoted supporters. Like the Black Nazarene, the Santo Niño (the Infant Jesus) is one of the most venerated religious icons in the Philippines.

The irony here is more complex than it seems. Duterte himself once pronounced that he doesn’t believe in religion. His controversial “war on drugs” attracted the strong disapproval of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines. He also cursed the Pope, who arguably stands a few notches below Jesus in the index of holiness for many Filipino Catholics. Just recently, he called God “stupid.”

Still, in a country dominated by people who consider religion “very important,” Duterte enjoys a relatively high trust rating.

The Santo Niño meme drew flak from many netizens. Monsignor Joseph Tan, media liaison officer of the Archdiocese of Cebu, said that the meme was malicious and insensitive of other people’s faith. The Cebu Provincial Board also released a resolution condemning the meme as “blasphemous.”

What made the meme incite more anger was perhaps the sarcastic comment from Carlos Celdran, a staunch critic of both Duterte and the Catholic Church. “Pwet Señor,” Celdran said. It played a pun on “Pit Señor,” a religious chant of Santo Niño devotees. “Pwet,” on the other hand, means “butt” in Filipino. Many cried sacrilege, to which Celdran replied that the joke was aimed at Duterte, not at the Santo Niño.

“But then again,” he added, “if you cannot tell the difference between the two, that isn’t my problem anymore.”

This episode leaves a trail of moral confusion. What are people upset about? Is it Celdran’s affront to a religious icon, the Child Jesus, or an affront to Duterte, the other messiah?

Jonathan Swift’s warning could not be more useful here. “Satire is a sort of glass,” he says, “wherein beholders do generally discover everybody’s face but their own.” The meme reveals a problem not so much with the subject of satire as it does with the satirist. Instead of illustrating that Duterte was not at all worthy of veneration, the meme misfired and backfired, only reinforcing the public’s devotion to Duterte.

When people do not find satire funny, it can be alienating. Jokes that fail to resonate breed contempt and heighten toxicity in our public sphere. In the age of political polarisation, satire, at best, is useful in comforting those who think the same way, but rarely does it make people in power uncomfortable.

3.

Decoding Duterte’s jokes is like reading hieroglyphics. Most of the time, we cannot tell whether he is cracking a joke or telling a lie, and we cannot distinguish between what is true, what is tongue-in-cheek, and what is outright false.

His supporters, meanwhile, have committed to defending what is usually indefensible – misogyny, killing, and profanity. Perhaps it is because they see the President as their Father. They call him “Tatay Digong,” which roughly translates to “Father Digong,” Duterte’s folksy moniker.

To pick a fight with Duterte is to pick a fight with a member of the family, as if a war were launched against their whole clan. Every time we make fun of Duterte, we also poke fun at his millions of supporters, who have had enough of the nation’s self-flagellation and, ironically, found esteem through Tatay Digong’s vulgar populist tirades against the establishment.

Check out yet another meme from The Superficial Gazette. It was posted on the day then Supreme Court Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno was ousted through a quo warranto petition, which law experts deemed unconstitutional.

By comparing Duterte to Thanos, the main villain in Avengers: Infinity War, the meme hints at Duterte’s invincibility.

Now that Duterte has collected all the “impunity stones”—a pun on “infinity stones”—the meme calls people to action, to speak truth to power. The text sends a clear message: “Only we, Filipinos, can stop him.” The enemy is not Duterte himself anymore, but something even greater, like the harmful ideologies he represents.

When we lose all our rights, when we let the system control every bit of what makes us free individuals, there will no longer exist a distinction between Duterte critics and supporters. Like in the film the meme alludes to, each one of us can, as it were, disintegrate into dust in a single snap of the cruel fingers of authoritarianism.

Has the meme made a dent on Duterte’s legitimacy? Not at all. No meme has ever stopped a tank. But it is a potent reminder that it is never enough to make fun of Duterte. The institutions he attacks need to be defended, especially if those institutions enshrine the very foundations of what makes the society we live in informed, free, protected, just, and humane. What would make Duterte more uncomfortable than the thought that, no matter how hard and how many times he snaps his fingers, he could never tear them all down?

Duterte’s selective human rights record

The first in our series of perspectives from young writers from Mindanao on two years of Dutertismo.

We can’t beat Duterte in his own game of jokes and incongruous theatrics. He is the best actor in the theatre of the absurd, rendering meaningless the facets of our individual and collective lives from which we derive reason and purpose.

Perhaps it is time for us to find a different approach, the kind in which we are never afraid to understand and explain, in which we are never afraid to be unambiguous, in which we are never afraid to appear serious. The moment in which we live is not a time for games.

Only when we, his critics, become a stark contrast to him can we finally reveal that behind Duterte’s veneer of authenticity lie his falsehoods and contradictions.

Jade Mark Capiñanes is a prize-winning writer in the Philippines. He is based in General Santos City. He tweets at @jademcapz.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss