A big focus for New Mandala over the years has been mainland Southeast Asia’s frontier regions. Many commentators on this site become attracted to these areas through adventure. ‘Adventure’, though, may not be the word a North Korean would first use to describe their perilous journey to reach freedom through these frontiers we otherwise take delight in exploring.

The stories of asylum-seekers are particularly important as they give an insight into crimes being committed in North Korea. Perhaps collectively, asylum-seekers’ personal stories may have an impact. Michael Kirby (the former Justice of the High Court of Australia), who was recently appointed as head of the North Korea Human Rights Commission, believes that asylum-seekers will be his chief source of evidence. Perhaps the testimonies of some of these survivors will make their way into the Commission’s report.

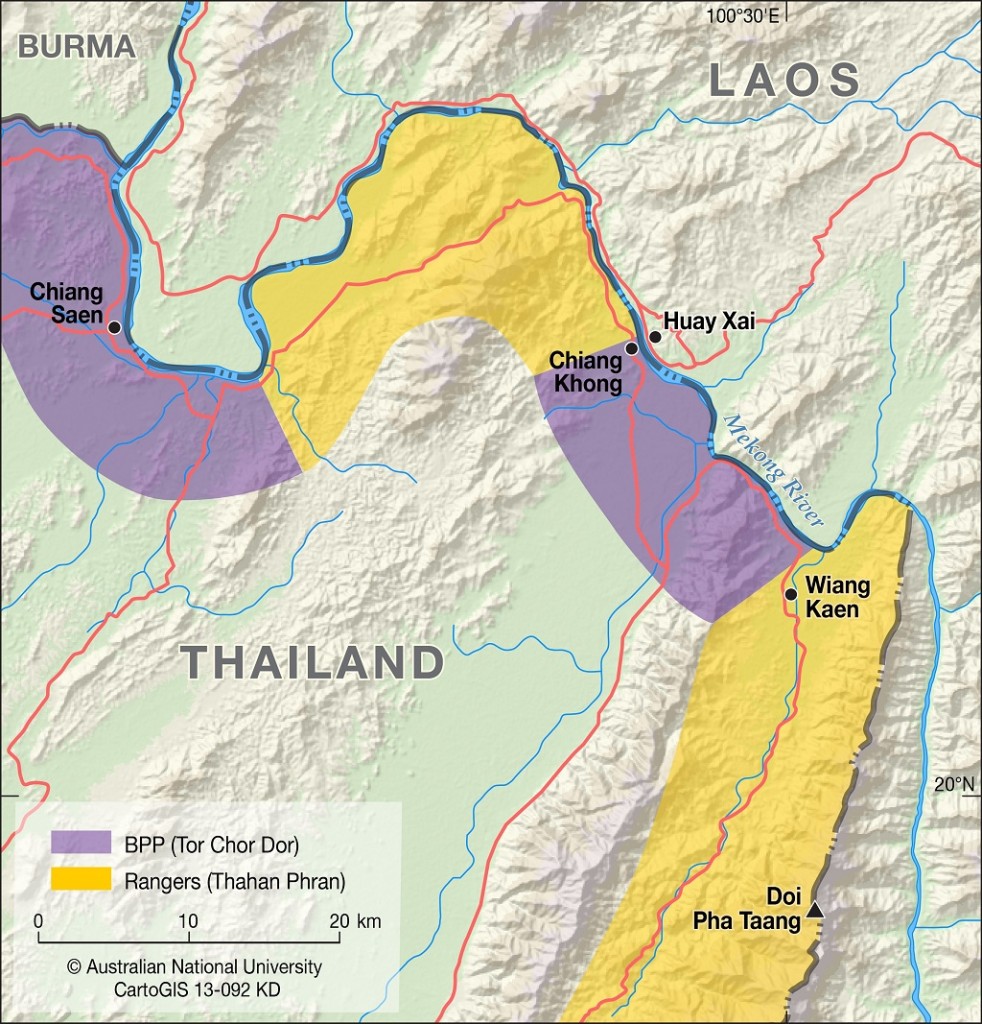

Since around 2004, the northwestern part of Laos has been used by North Korean asylum-seekers in transit to Thailand, after a long and harrowing journey from North Korea down through China. From Thailand, they are resettled in South Korea. More than a thousand crossed the Mekong River into Chiang Saen, Chiang Khong and Wiang Kaen Districts of Chiang Rai Province in 2004-07. According to a Bangkok Post article from 6 May 2011, the number of North Korean asylum-seekers was rising (reaching 2,482 North Korean arrests in 2010). But in 2012, the South Korean reunification ministry reports a decline in the number of Northern defectors reaching the South.

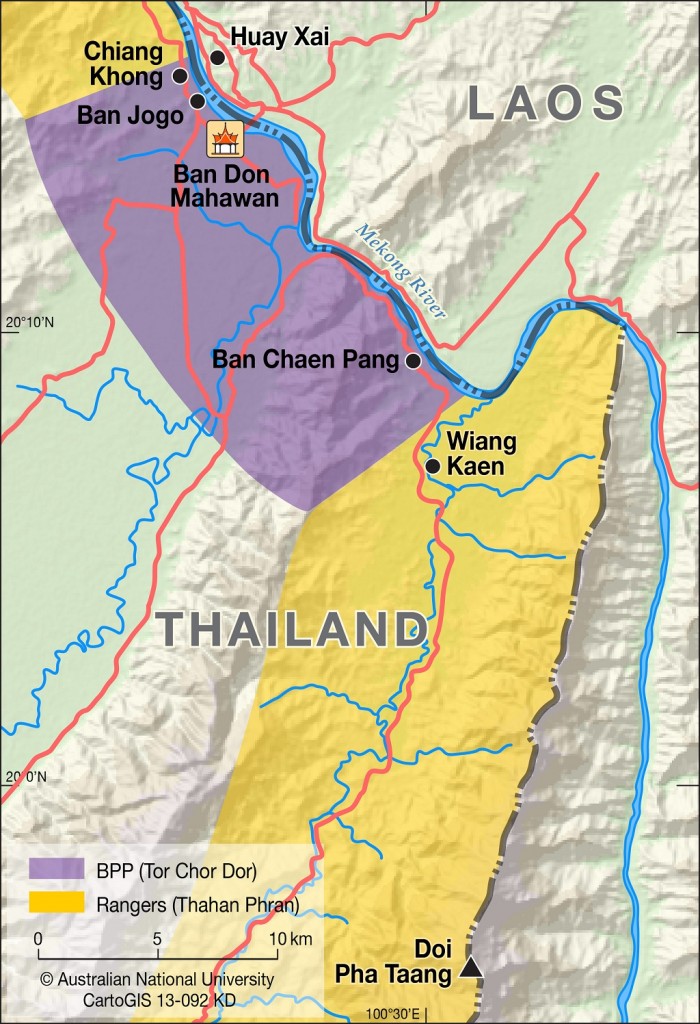

As previously highlighted on New Mandala, a regiment of the Thahan Phran (Rangers) was formed in 2005 for special duties along the Mekong River in this region. The Rangers have been stationed at numerous places along the Mekong River. Many of these are clustered from Chiang Khong to Chiang Saen, and from Wiang Kaen southwards. Asylum-seekers found in these areas are usually detained by Thahan Phran units who beat and abuse them. Yet, there is a gap between Chiang Khong and Wiang Kaen townships that remains controlled by the Tor Chor Dor (Border Patrol Police, henceforth BPP).

Desmond Ball and a Chinese-speaking friend encountered this group of asylum-seekers (two men, eight women and one girl) who arrived at 10am at a camp of the 326th BPP company at Ban Jogo near Chiang Khong on 30 April 2013. They were found at a temple near Ban Don Mahawan, where they had been residing undetected for about two weeks. Prior to arriving at the camp, they, including the girl, had not eaten in two days.

The asylum-seekers had crossed the Chang Bai Shan (or in Korean, Baekdusan) mountain range, and then apparently made their way by bus to Qingdao. From there, they took a bus to Kunming. They then spent five days hiking through the mountains to get a boat headed down the Mekong. This may not have all happened at once in a great escape. For instance, many North Korean asylum-seekers spend time in Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture to work up enough credit with people smugglers to make their way to Thailand. This would explain the Koreans’ Chinese language abilities. With the help of Ball’s Chinese-speaking friend and a BPP member who could speak Chinese, the asylum-seekers communicated their names and ages.

The BPP gave them access to showers, and provided food. One of the women had fresh wounds on her face. There was a lot of trepidation amongst the asylum-seekers about what BPP transport they would travel in to go the police station. The asylum-seekers took around a half an hour to work out seating arrangements, much to the frustration of the BPP members who waited patiently. Eventually they departed for Chiang Khong Police Station at around mid-day.

It is interesting that armed BPP members did not seem to intimidate the North Koreans, who were presumably used to heavy state oppression. Confusion over seating arrangements may have been exasperating for the members of the 326th company, but imagine the decision from the perspective of an exhausted and paranoid North Korean. You might fear not seeing your friends getting in a different car ever again.

During the two hours the asylum-seekers had been at the 326th BPP company camp, contact had been made with the South Korean Embassy (after around an hour and a half) in relation to their presence. Bangkok has an agreement with Seoul to transfer asylum-seekers to the South. Vientiane and Beijing, however, do not. If caught in China or Laos, these asylum-seekers would likely have been returned to the North and would have faced a harrowing, and probably very brief, future.

Some of the asylum-seekers who had seen the plentiful bananas at the camp were apprehensive about whether or not they could have some. A BPP member gestured that they could have as many bananas as they liked, and by the time they departed for Chiang Khong police station, there were none left. One of the BPP said that similar-sized groups arrived in Chiang Khong District about once a week.

* * *

In addition to the BPP and Rangers, North Korean asylum-seekers are also sometimes interdicted crossing the Mekong River from Laos to Thailand by the Royal Thai Navy’s Mekong River Task Force, which has one of its main bases in Chiang Khong. For example, on 31 May 2013, thirteen North Koreans were arrested by the Task Force in the Chiang Khong area.

Des Ball is a Special Professor in the Australian National University’s College of Asia and the Pacific. Colum Graham is a graduate student at the same institution. In late 2013 Ball’s two-volume study of Thailand’s Border Patrol Police will be published by White Lotus.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss