In the wake of informal talks, Thailand’s military junta must make peaceful resolution of the ongoing conflict a priority. But as insurgents demand greater sovereignty, that seems unlikely.

On 25 August, representatives of Thailand’s military government met with a coalition of Malay insurgents, Majlis Syura Pattani, in Kuala Lumpur.

It was the third round of preliminary talks that aim at restarting formal peace talks.

The first two rounds were held in secret in June, with few details emerging. This round was followed by an unprecedented press conference by the representatives of the six groups and factions that comprise Mara Pattani, as the group of insurgents is commonly referred. The head of the Thai delegation General Aksara Kerdphol immediately declared the talks a “success.”

While talks are important, not too much should be expected. These are still very preliminary meetings and the likelihood of a formal peace process is a very long way off.

The Mara Pattani delegation included seven representatives: Awang Jabat, Ahmad Chuwo, and Sukri Haree from the Barisan Revolusi Nasional (BRN); Ariee Muktar from Pattani Liberation Organization (PULO); Abu Ah Gim Hassan from Pertubuhan Pembebasan Patani Bersatu (PULO-DSPP); Dr Abu Hafez Al-Hakim from Barisan Islam Perbersasan Patani (BIPP); and Abu Yasin from Gerekan Mujahidin Islamiya Patani (GMIP). The PULO faction headed by Samsudin Khan did not participate in the talks.

The BRN, which is the group most responsible for the violence in Thailand’s Deep South that is now in its 12th year and which has caused the death of some 6,400 people and over 15,000 casualties in total, leads Mara Pattani. Awang Jabat, who was identified as the head of the BRN’s armed wing, is its chairman, while Sukri Haree serves as its lead negotiator.

In this context, the mere existence of Mara Pattani is important.

The previous round of talks held by the government of Yingluck Shinawatra were almost exclusively with the BRN. Indeed, members of PULO actually detonated a bomb on Ramkamhaeng road in Bangkok on 26 May 2013, just to wrest a seat at the table, but rivalries hindered cooperation.

Although the Thai junta claims that the talks broke down because of the political stalemate in Bangkok that broke out in 2013, subsequently being formally suspended by December that same year, the reality is the Royal Thai Army had quashed any attempt by the government to make concessions at the talks; they were effectively dead by August 2013, long before Thailand’s political unrest.

Mara Pattani was created through the concerted efforts of Malaysia, in particular Zamzamin Hashim, the former head of the Malaysian External Intelligence Agency, which has been frustrated by divisions within the Pattani community.

BRN’s Awang Jabat (second from left) chairs Mara Pattani. Photo: AFP.

Members of Mara Pattani aren’t equal partners. The BRN commands the majority of militant cells on the ground and has bristled in the past when other groups have tried to leverage political gains from a weak military position. Some groups, such as the BIPP are not involved in militant operations, but Dr Hafez does command respect and has ideological sway.

Dr Hafez explained that the goal of Mara Pattani was to “seek a just, comprehensive and sustainable political solution together,” and that it would serve as a “consultative platform for all Pattani liberation movements, civil society organisations and non-governmental organisations, local politicians, professionals, and academics who are legible.” As such, the umbrella grouping has five immediate goals.

These are: to promote unity and collectively shoulder the responsibility with the people of Pattani for the right to self-determination; to maintain a conducive, progressive and continuous political struggle; to create space and opportunities for all Pattani liberation movements, civil society organisations and others to voice their opinions, make suggestions and come to a collective decision to determine the group’s political position at the peace talks; to create an opportunity for professionals and academics to provide opinions, arguments and evidence, in their respective fields, in support of the negotiating team; and to gain the confidence, assistance and support for the struggle of Pattani from the international community.

It’s important that there is a common, platform at least at the outset. In 2013, the rebels were all over the place, issuing pre-conditions after talks had already begun, including some they knew the military would never accept. Not only are the factions finally speaking with an increasingly – though not completely – unified voice, they are also acting more professionally.

Mara Pattani set out three pre-conditions for formal peace talks.

First, they demanded that the Thai government make the Deep South a priority on its national agenda. Second, that the government recognise Mara Pattani as a legitimate organisation; and third that Mara Pattani representatives be given immunity and safe passage throughout the south.

These were concrete, reasonable and functional demands, without which, they cannot do their job and represent their constituents in formal peace talks.

And yet, the government has yet to formally agree to any of these demands, simply noting them: “the terms were received and will be considered along [with] the process”.

A member of the Thai delegation General Nakrob Bunbuathong said, “We accept Mara Pattani, as we talk to them.” But that is not formal recognition and to date Prime Minister General Prayuth Chan-ocha has not referred to the grouping.

The insurgents are right in trying to compel the government to make the peace process a national priority. “Setting this issue as a national agenda is an important matter, because if it is not a national agenda, there will be no continuity in the dialogue.”

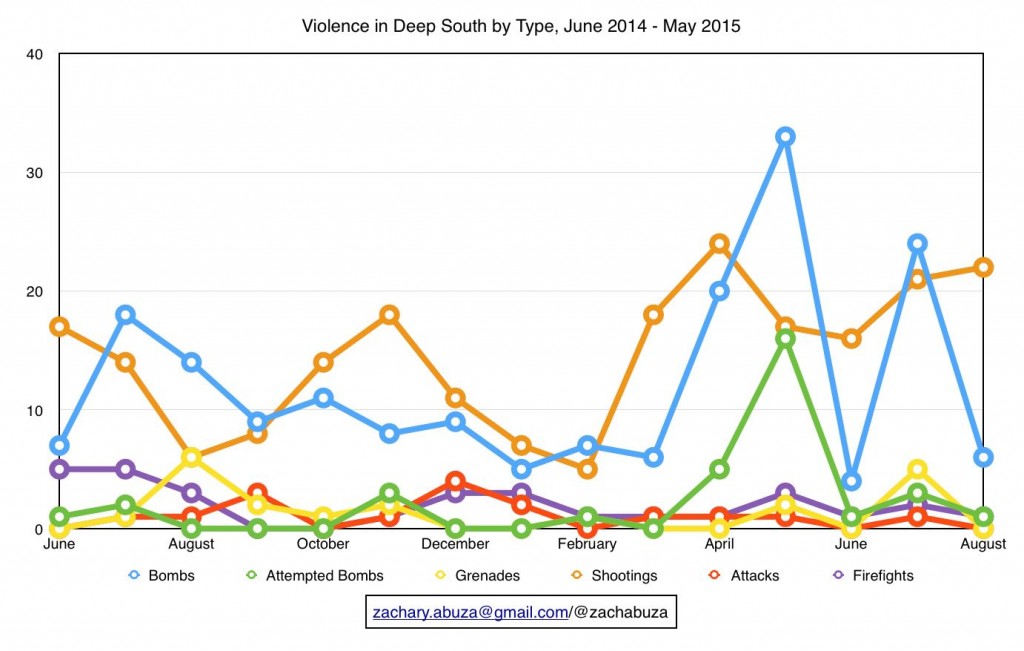

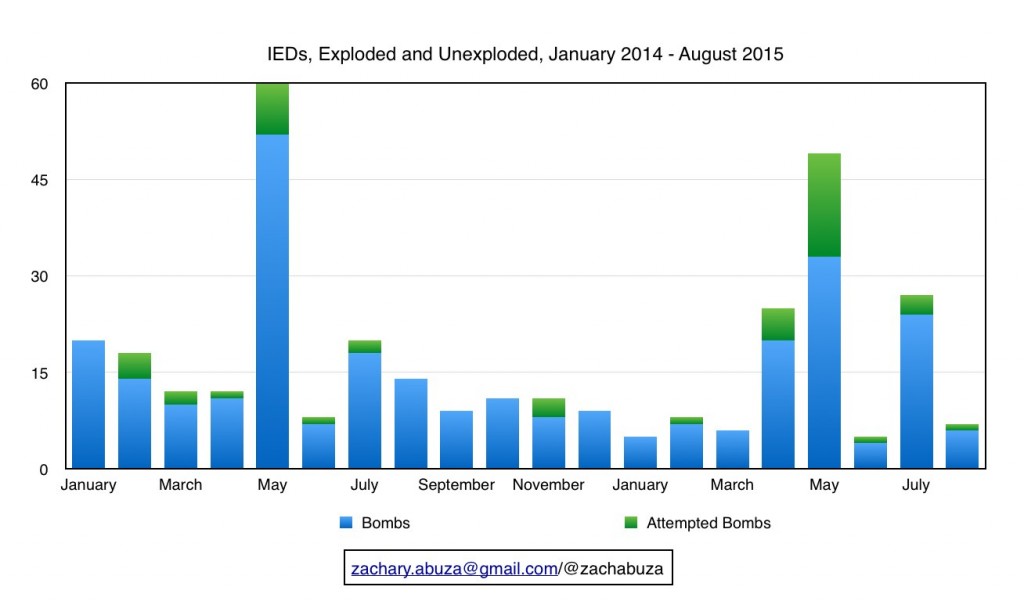

And yet, in their 15 months in power, the junta has paid little attention to the Deep South. The violence, which has remained mostly contained – though it seeped out in April 2015 when a cell detonated a bomb on the resort island of Koh Samui – is an irritant, but not an existential threat to the military and their monarchist elite backers.

This seems unlikely to change considering the host of other issues the junta has to address. Passage of their botched constitution, revitalising the moribund economy, dealing with the imminent royal succession, and investigating the Bangkok bombing which threatens the tourism industry that accounts for 10 percent of GDP will be a priority.

To be fair, General Aksara Kerdphol said that he would forward Mara Pattani’s demands to General Prayuth for endorsement, but the Royal Thai Army has steadfastly resisted even the slightest concessions in the past. Hopefully this attitude will change, now that it is in charge, no longer simply the spoiler.

The Thai side issued their own demands: the creation of a “safety zone” in the Deep South, “economic development,” and “justice for all”. The Thai government’s demands are at best vague, and at worse undermined by their own actions and policies.

The government wanted one place in each of the 41 districts across the provinces of Narathiwat, Yala, Pattani and parts of Songkhla that have been affected by the insurgency to be guaranteed free of violence. This would then be expanded.

This proposal seems to be a non-starter with the insurgents, who, with fewer capabilities and resources want no further limitations on their operations. They proposed just one safety zone for the entire south.

The Thai government insists on these safety zones as a sign of goodwill but also a demonstration of insurgent command and control. But the insurgents have their own concern about command and control on the Thai side.

The delegation of security to Rangers and other poorly trained volunteers (ie the “Thung Yang Daeng Model“) has led to some egregious attacks, and there is also some Buddhist vigilantism that too often seems to be sanctioned, or at least tolerated by the Thai state.

One of the government’s proposals was “justice for all,” and yet, it is the government’s continued failure to assure justice for the ethnic Malay community and the total impunity that security forces operate under, that remain the single largest irritants.

Indeed, just four days before the KL talks, a court in Songkhla ordered the Prime Minister’s office to pay US $22,000 in compensation to the family of a man who was tortured to death while in detention in July 2007.

While that award was unprecedented, the court’s refusal to recommend that any of the security officers involved in the case be criminally prosecuted was all too familiar. The military government cannot be expected to rescind the blanket immunity that all security forces have operated under in the Deep South since July 2005.

The insurgents have put the ball firmly in the Thai court.

They have refused to renounce violence or maintain a ceasefire. While they have reduced the amount of targeting of civilians, they have not stopped, despite Awang’s assertion to the contrary.

“We have no policy of attacking soft targets,” he said. “We focus on hard targets. Sometimes, soft targets are affected, but they are victims of collateral damages.”

This is nonsense.

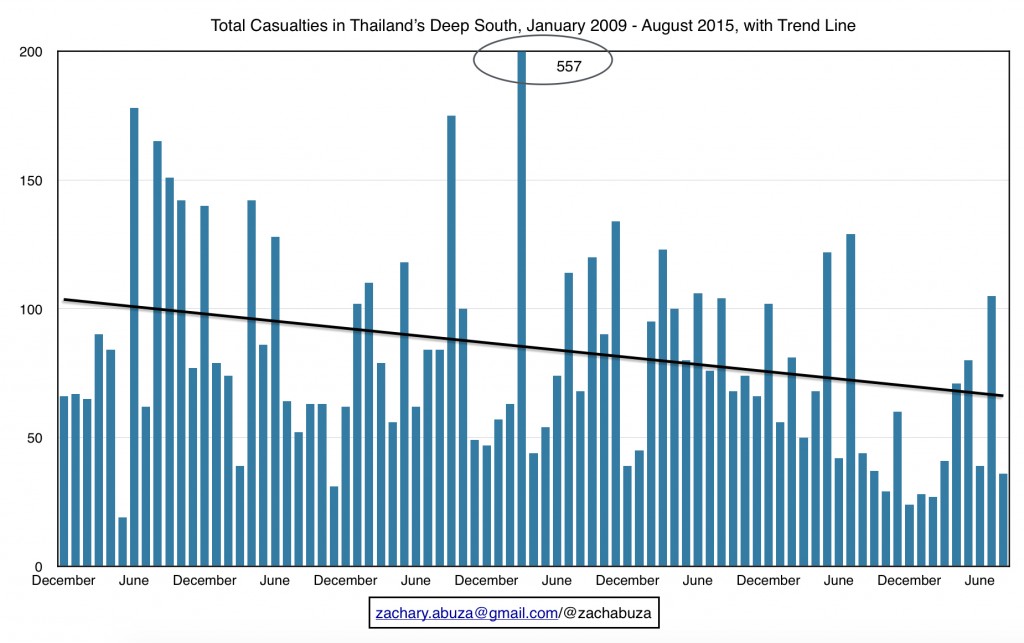

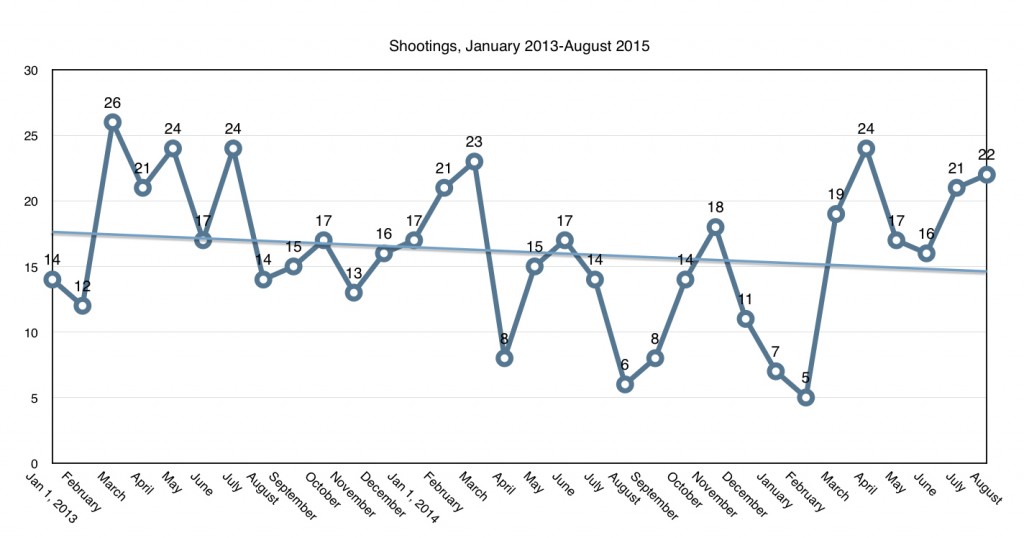

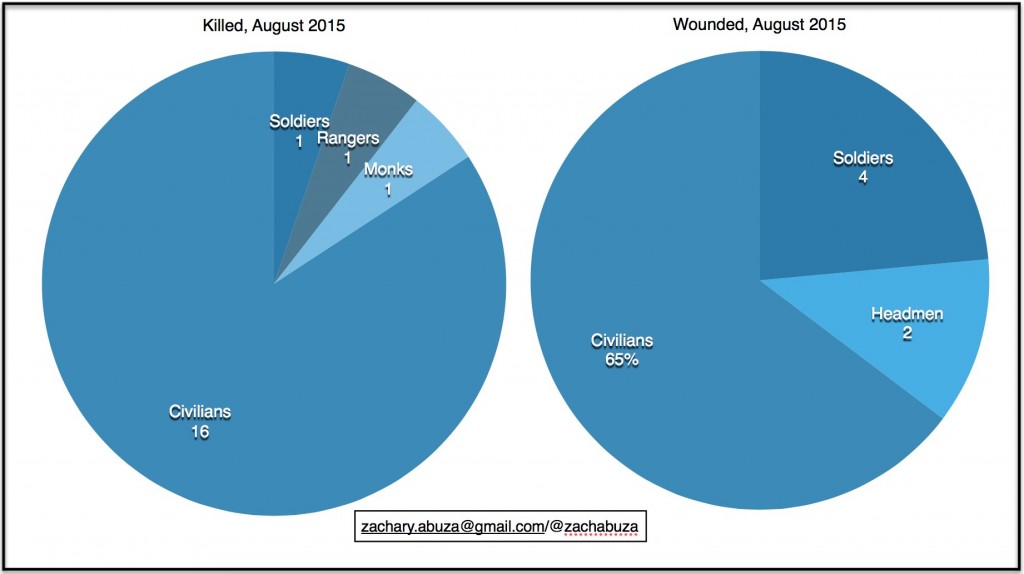

Since 2009, security forces have only accounted for 40 per cent of total casualties. In August 17 of the 19 killed were civilians, while only four of 17 of those wounded were members of the security forces.

There is monthly variation in the violence that is caused by a myriad of factors, from stepped up operations by government forces, to tactical retreats, to the weather, to logistical logjams. The government, for example took credit when violence in this year’s Ramadan fell.

While true – it was low in the first two weeks, leading to only 39 casualties in June – it spiked in the second two weeks of Ramadan, when security was still in force. There were 105 casualties in July, including 26 dead, the second highest monthly tally since the May 2014 coup.

And while the average number of casualties has declined since the start of 2009, it has not declined by that much, with insurgents able to escalate the violence as they see fit.

They are also able to move out of the area, which they have cautiously done. Take for example the April 2015 bombing in Koh Samui, which should have sent a clear signal to the junta.

While Awang stated that the insurgents were seeking peaceful means, he was under no illusion that it would happen anytime soon.

Our principle is to find a solution through peaceful dialogue. We hope we can bring the conflict to an end and promote a lasting peace. Mara Pattani is aimed at a peaceful means of fighting. As for the current fights with forces and arms, we will need to reach a stage where both sides can stop such violent means, it is up to how we can build mutual understanding and trust.

Another important point to come out of the talks is that the insurgents publicly stated, what was long believed, but never confirmed, that the goal is secession. “The demand was not expressed in peace talks at this time, but it is the main agenda of our group,” said Awang.

Until that is achieved, Mara Pattani’s main goal is to “ensure the rights and interests of the people of Pattani are heard, considered, discussed and fought for, consistently, systematically and concretely… It’s about self-determination, not secession or separation.”

A fourth round of preliminary talks is expected to be held later this month, with the goal of having a signed agreement that will lead to the start of formal peace talks. But even then, peace is a long way off.

The Thai government’s draft constitution consolidates power in the hands of monarchist and military elites who have been fixated on centralising political power. There is no space in the new constitution for a significant devolution of power that would satisfy the members of Mara Pattani.

It is inconceivable to seeing the government offer significant autonomy – political, linguistic/cultural or economic – for the fear of a precedent that it would create. It also seems improbable that the Thai government will agree to the BRN’s five demands laid out in 2013, including recognition of the “sovereign rights of Pattani Malays on their land”.

Zachary Abuza is a principal at Southeast Asia Analysis specialising in regional politics and security issues. He has authored numerous books including Conspiracy of Silence: The Insurgency in Southern Thailand(2008) and Militant Islam in Southeast Asia (2003).

Download Zachary Abuza’s charts on violence in Thailand’s Deep South here.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss