Criminal defamation raises its ugly head in Timor-Leste, writes Jim Nolan.

An article in The Timor Post on 10 November 2015 which dealt with the letting of government tenders for IT services, has triggered draconian criminal defamation laws against the journalist concerned.

This disturbing development comes at a time when the government in Timor Leste is poised to formally appoint the members of its newly minted Press Council – the key body in a legal framework intended to deal with complaints against the press principally by mediation. Yet, in this case, this new scheme of press regulation, which has been in the works for several years, was entirely side stepped.

This disregard for the new complaints mechanism is all the more puzzling since the newspaper concerned followed the precepts of the new press law in dealing with the complaint – including by publishing a prominent and timely correction to the one part of the story which contained an error.

Yet this was apparently not good enough.

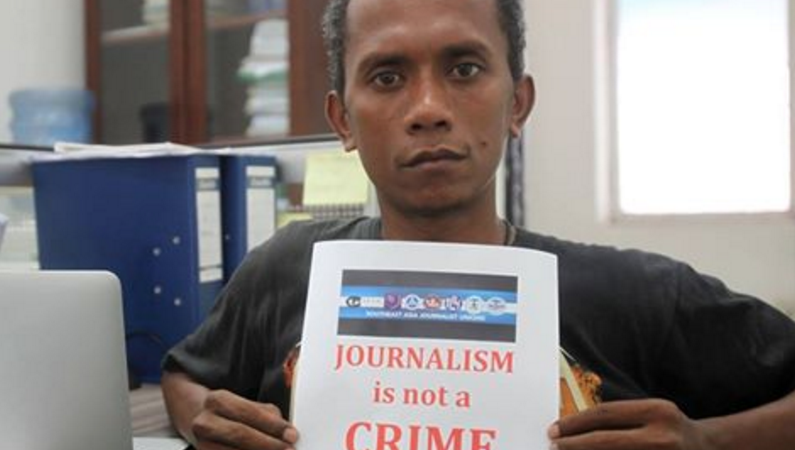

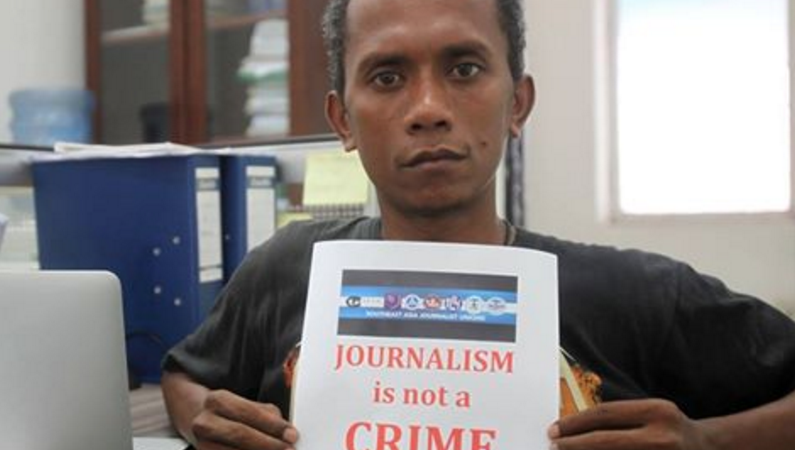

It is uncertain why, because no dissatisfaction was expressed with the timelines or adequacy of the correction. Indeed, nothing more was heard until the journalist, Raimundos Oki, received a ‘summons’ from the Prosecutor General’s Office in Dili that the story raised a breach of s285 of the criminal code – a bizarre and dormant version of criminal defamation.

It may be no co-incidence that the subject of this piece of investigative reporting was a former adviser to the Finance Minister, and now current Prime Minister, Dr Rui Maria de Ara├║jo.

The summons required Oki and his former editor, Lourenco Martins, to attend the office of the Prosecutor General on Monday 11 April. Appearing with their lawyers, each faced separate 30 minute interviews.

Both men relied on their right to silence, and the prosecutor read a statement that left them none the wiser as to the substance of the complaint and how it could give rise to breach of s285. Each was given a ‘letter’ stating that neither could change his address nor travel overseas without giving the prosecutor 15 days’ notice. Although these conditions are not on their own onerous, as a matter of principle they are repugnant because they place legal restrictions upon the free movement of the two men. They add a further ‘chilling’ note to an already objectionable law.

The prosecutor must now decide whether to file an indictment or drop the charges. The time permitted for the prosecutor to gather evidence and to make a decision about this is unclear.

Former occupier Indonesia provides a salient lesson in Timor-Leste can do press freedom better.

Journalists in Indonesia have struggled fiercely since the fall of Suharto to resist and defeat criminal defamation prosecutions, but over the past two decades, criminal defamation cases against Indonesian journalists have steadily declined; so much so, that the last trial, in Makassar in 2010 resulted in the first acquittal in a criminal defamation trial. The acquittal marked a significant victory for the Indonesian journalists’ campaign – all the more since the complainant at whose behest the charges were pressed was the outgoing Police Commander of South Sulawesi!

It is a supreme irony that criminal defamation, having been sent into retreat in Indonesia, has now surfaced in democratic Timor-Leste.

Under s285 of the Criminal Code, where publication of a story by a journalist who is ‘‘aware of the falsity of the accusation, informs or casts suspicion on a person regarding commission of a crime, with the intent of having criminal proceedings initiated against said person…,” the journalist faces up to three years imprisonment or a fine.

Thus, the prosecution must establish four conditions. Firstly, the publication of the ‘accusation’. Secondly, at the time of publication, the journalist must be “aware of the falsity of the accusation,” and thirdly, the accusation must concern the “commission of a crime” and fourthly, the publication must be made “with the intent of having criminal proceedings initiated against the person.”

At the heart of this offence is the requirement to prove deliberate, premeditated malice to bring about a false and malicious prosecution of an innocent person. Any criminal statute must be interpreted strictly and narrowly. It follows that each of the elements of the offence will need to be proved according to the criminal standard of proof.

There are two key stumbling blocks to the charge under s285. As observed, the journalist concerned must be “aware of the falsity of the accusation”. There is no suggestion that any proof exists of this ‘state of knowledge’ on the part of either journalist. In the absence of any prima facie, or sufficient proof of a state of knowledge, the prosecution cannot get past first base. Only a ‘confession’ or clear documentary proof tying the alleged perpetrator’s state of knowledge to the story would be sufficient to raise a prima facie case. None exists and, in the interview, nothing was put to Oki to suggest that it did.

The second major stumbling block is that the publication was made “with the intent of having criminal proceedings initiated against the person”. Quite how a journalist could publish a story with that precise intent is not at all clear. The journalist may be of the opinion that the content of the story (if true) merited a criminal investigation and the filing of charges. However the decision to commence criminal proceedings is entirely a matter for the Prosecutor-General’s office.

Since the journalist’s actual knowledge is the essential ingredient of two elements of the offence, the failure to confront Oki with the ‘evidence’ of his alleged state of knowledge is troubling.

On its face then, the investigation appears to be no more than a fishing exercise directed to finding material to ‘fit’ the contorted features of the ‘crime’ created by s285.

The question must be asked whether it is a proper exercise of the Prosecutor’s function to investigate an alleged ‘crime’ where no prima facie evidence points to any offence under s285.

On its face, any exercise of investigative journalism directed to exposing public malfeasance would be ripe for investigation under s285.

Such a development is antithetical to the clear expressions of freedom of the press embodied in articles 8 and 9 of the Press Law which establish a right for journalists not to be subjected to any interference that threatens their independence and objectivity, and the right to freedom to expression and to be free from harassment.

There has been no credible suggestion that Oki reported the story other than with the intention of informing his readers on an important matter of public interest.

Oki’s case presents the newly established Press Council with its first significant challenge. The Council has powers to deal with complaints against the Press which are regarded as potentially unduly restrictive of press freedom. Notwithstanding concern about the powers of the Press Council, the consensus appears to be that the persons named to the Council are good appointments and will have press freedom as their overwhelming concern.

The members of the Press Council will be formally invested by Parliament on Press Freedom Day 2016, 3 May. This will be an interesting event given the present investigation.

Jim Nolan is a Sydney Lawyer who has acted as a pro bono legal adviser to the International Federation of Journalists (Asia Pacific) for many years. He has attended trials in Indonesia as a legal observer for the IFJ and participated in numerous activities promoting Press Freedom and opposing criminal defamation in Indonesia. He attended the Prosecutor Generals Office in Dili on Monday April 11, as legal observer on behalf of the IFJ to support Oki.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss