Hew Wai Weng illustrates the various aesthetic forms that are popular among middle-class Muslims in contemporary urban Malaysia and Indonesia.

One afternoon in early February, just a few days after the Chinese New Year, I visited Al-Saadah Complex, a recently-built Chinese-style mosque in Seremban, Malaysia, to observe Friday prayers.

The mosque’s architecture was inspired by the Great Mosque of Xi’an in mainland China. Various Chinese features dominate both the exterior and interior of the complex, including the entrance gate, the courtyard and pavilion, the red pagoda-shaped minaret, red lanterns and Chinese calligraphy. Such architectural statements declare that ‘there can be a Chinese way of being Muslim’.

Sometimes mistaken as a Chinese temple, the Seremban Al-Saadah Mosque Complex is one of the newly established Chinese-style mosques in Malaysia.

After the prayer, a couple of Chinese Muslims distributed free mandarins to visitors, most of whom were Malay Muslims. I had a short conversation with the head of the mosque’s managerial committee, Mohd Adnan, who is an Indian convert. He told me that the religious authority of Negeri Sembilan, the state where the mosque is located, had given the mosque the rights to draft its own Friday sermon in Mandarin. In addition, every Saturday morning, there is a free Tai-Chi class at the compound, and the mosque has continuously hosted Chinese New Year celebrations since its establishment in 2011.

Afterward, I drove to Bangi Central, about 30-minutes from Kuala Lumpur. A newly-established business district, Bangi Central is now the most popular Muslim fashion hub in Malaysia. It is also a haven for pious middle class Muslims to ‘eat, pray and shop’.

Packed with trendy Muslim fashion boutiques and chic halal cafés, Bangi Central is a popular hangout and shopping place for Muslim youth.

Located not far from the main mosque of Bangi, Al-Hasanah Mosque, Bangi Central is packed with stylish Muslim fashion boutiques and dotted with many hip cafes and restaurants. Some shops creatively combine both as ‘boutique café’ — one can check out the latest fashion trends, while sipping a cup of coffee and eating cake.

Inside one of the many boutique-café in Bangi Central—Tudung People: the left part sells fashionable headscarves, while the right side serves ‘sinful’ drinks (creamy iced coffee).

Live performance of making Lanzhou hand-pulled noodle, by Hui migrants from China in a Hui restaurant in Bangi Central.

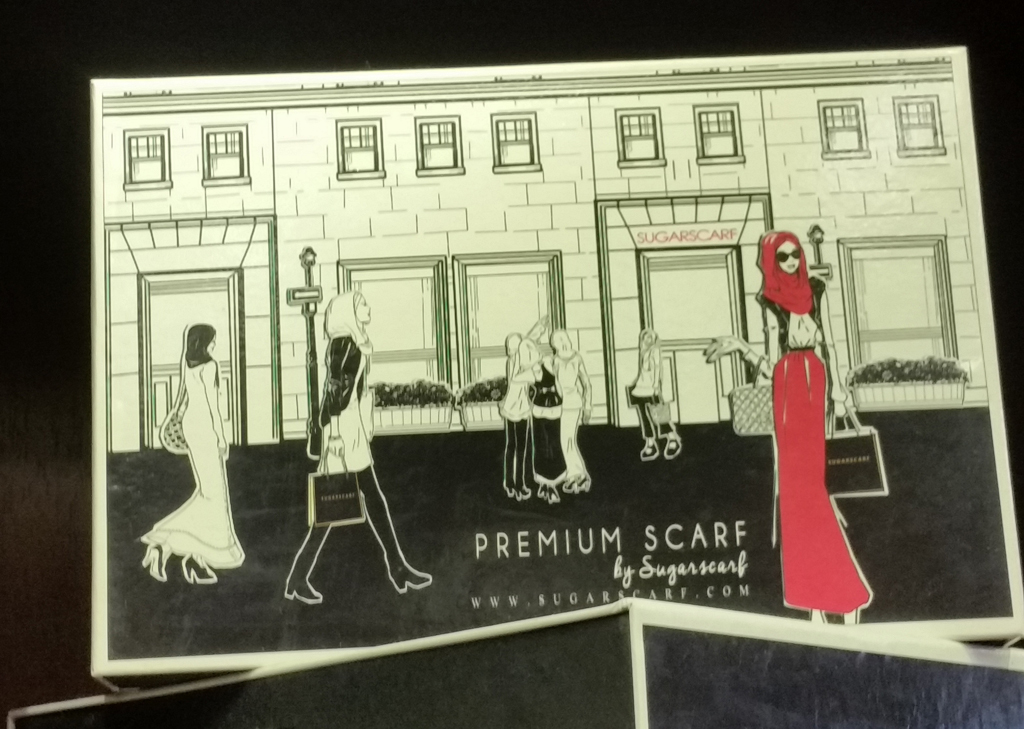

My day in Bangi began with a short visit to a fashion boutique, called Sugarscarf, which sells various exclusively-designed headscarves. The shopkeeper explained that the interior setting of the boutique was inspired by English vintage design. Decorations included photos of young females wearing scarfs and sunglasses with European streetscapes in the background.

A photo display in the Sugarscarf Boutique, featuring young women wearing fashionable headscarves and hip sun-glasses with European streetscape as backdrop.

French chic, English vintage design, Kufic inscription and Chinese calligraphy are among the many aesthetic features that characterise Bangi’s shops. Interestingly, not many of the fashion boutiques use Malay language. As one girl told me, ‘Of course, we are not going to use names such as Azizah to brand the boutique. It sounds outdated and not cool’.

A combination of English vintage and French chic design makes Sugarscarf boutique in Bangi Central look cool.

English words are prevalent, such as Sugarscarf and Pretty Pop for brands; ‘Stylish, Modest, Elegant’ and ‘A Story for Your Wardrobe’ for taglines. Of course, there is no lack of modern Arabic names, such as Q’Manda and Zawara. Others use combinations of two languages, such as Tudung People, Aisya Queen, Siti Castle and Bella Ammara.

Chemistry Café+Lab on the ground floor, Osra Muslimah Boutique on the first floor and AisyaQueen boutique-café on the second floor—Bangi Central is full of eating and shopping options.

Such creativity and diversity is not only reflected in the names, but also in the styles. These trends might show that while many female Muslim youth do not directly challenge ‘Islamic conservatism’, they do not see themselves as ‘victims’ of Islamisation. Instead they negotiating the growing conservatism in a creative and playful way through fashion.

Either in the form of car stickers, photo displays or T-shirts, Kufic inscription is one of the many preferred aesthetic forms among urban Malay Muslims.

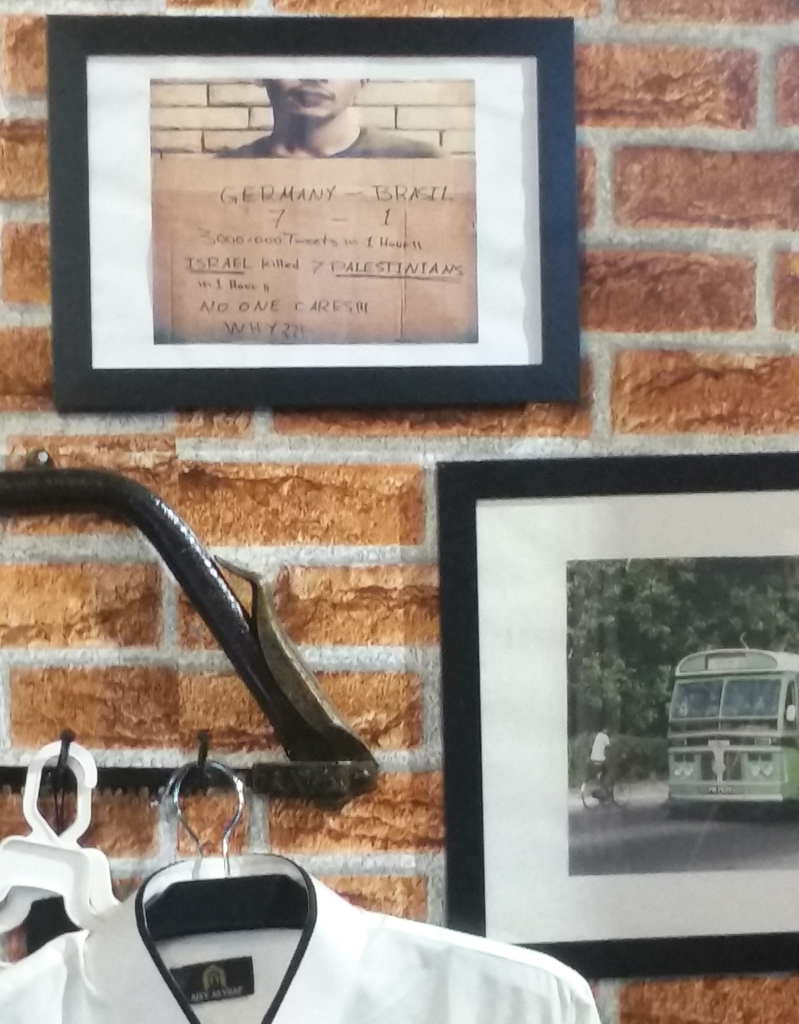

Photo 11: A photo display in one of the fashion boutiques write: ‘Germany – Brazil: 7-1 3,000,000 Tweets in 1 hour!! Israel killed 7 Palestians in 1 hour!! No one cares!! Why??’.

While most of the fashion boutiques cater to female Muslims, there are a few targeting male consumers. I talked to a few owners of the boutiques selling trendy male jubah (a long robe, originating in the Middle East) and kurta (upper garment, originating in South Asia) with local variations.

A sign of religious piety or/and a form of fashion trend? One of the male Muslim fashion boutiques in Bangi Central sells locally-designed fashionable jubah, kurta and shirts.

One of them emphasized that, ‘The jubah we sell are different from what the Arab people wear. We are still culturally Malay. We are not becoming Arab because of wearing a jubah’. Indeed, the jubah in Malaysian fashion industries has been adapted to local taste and fashion trends, brightly-colored and form-fitting for example. While the jubah’s Arabic origins give it ‘Islamic authenticity’, wearing it doesn’t equate to religious piety. Hence, Malay Muslims may wear jubah today as a selective and creative adaption of ‘Arabness’, instead of a form of sweeping ‘Arabisation’; and as a fashion statement.

Decorated with golden domes and minarets, the Great Saladin Square is one of the vivid landmarks in Depok.

Negotiating Islamic piety and urban aesthetics is not unique to Bangi in Malaysia. Depok, a town in Indonesia within the Jakarta metropolitan region, shares similar characteristics. Built in 2010, the Great Saladin Square, a shopping mall decorated with golden domes and a minaret, is one of the most vivid landmarks in Depok. Developed by non-Muslim Chinese Indonesians, such ‘Middle-eastern’ architecture reflects ‘the religion of the majority in Depok’ which is Islam.

Yet, such features are only one of the many architectural forms in Depok. Surrounded by informal neighbourhoods (kampung), there are growing numbers of housing complexes that adapt the so-called ‘modern minimalist’ design. Many of the property developers are Muslims and some of them even claim their housing as ‘Perumahan Muslim’, a kind of Muslim-only gated community.

One of the examples is the developer Orchid Realty. Established around 2006, by the Organization of Cyber Housing and Islamic Development, it claims to be ‘Indonesia’s first Islamic property developer’ and offering a ‘modern, green and Islamic’ living atmosphere to young middle-class Muslim families. Most of the houses it has developed use English names, such as Orchid Residence, Cyber Orchid Park, The Orchid Town House and The Orchid Green Village.

‘Living in Modern, Green and Islamic Atmosphere’- A snapshot of an advertisement for the Orchid Green Village, a Muslim-only housing complex in Depok.

Another property developer, Bumi Darussalam, uses Indonesian names to label its housing complexes, such as Mutiara Darussalam, Pondok Darussalam, Permata Darussalam and Pesona Darussalam.

Pondok Nurul Fikri is another new Muslim-only housing project in Depok. Promoting the idea of ‘Islamic Green Living’ (previously ‘Islamic Smart Living’), Pondok Nuril Fikri combines both an Integrated Islamic School and Muslim gated communities, with a big mosque in the same area. While using the English tagline, the developers name its housing types according to Andalusian cities, such as Sevilla and Cordova, referring to the Islamic civilization, Al Andalus based in southern Spain from 711 to 1492.

‘Islamic Green Living’- A snapshot of an advertisement for Pondok Nurul Fikri, a Muslim-only housing complex in Depok.

In Bogor, another remarkable Muslim housing complex, Bukit Az-Zikra uses Arabic terms, such as Sakhoya, Gonaah and Syukur to name its housing types and adopts ‘Islamic’ features ( like the eight-sided star and the colour green ) on its minimalist-designed houses.

The diverse architectural idioms, fashion designs, branding, languages, signs and tastes, illustrate various aesthetic forms that are popular among middle-class urban Muslims in Malaysia and Indonesia. While piety and aesthetic are intersected in the processes of urban place-making, there is no direct correlation between them.

Yet, such aesthetic expressions might signal different yet intertwined orientations. For example, the use of English language and minimalist design implies the pursuit of ‘Western modernity’; the use of Arabic script and Middle-eastern form highlights the search of ‘Islamic authenticity’; while the use of Chinese calligraphy and architectural style reflects the quest for ‘cultural diversity’.

How do these diverse aesthetic forms relate to each other, co-exist, converge or contest? And what can they tell us about religious piety and urban lifestyle among urban middle-class Muslims in Malaysia and Indonesia today?

Hew Wai Weng is a visiting research fellow at ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore. He is currently researching on ‘Religious Gentrification: Islam, Middle Classes and Place-Making in Urban Malaysia and Indonesia’.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss