In 1956, at the height of the Cold War, John D. Rockefeller 3rd established a new organisation known as Asia Society. Rockefeller’s intention was to promote mutual understanding and engagement between America and Asia, and he saw art as fundamental to this mission. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Rockefeller and his wife Blanchette worked together with their advisor, also then the Director of the Cleveland Museum of Art, Sherman E. Lee, to assemble the now-renowned Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection. The collection was assembled with the intention of ultimately giving it to an institution for public view. Following JDR3’s untimely death in 1978, part of the collection was bequeathed to Asia Society, forming the beginnings of the Asia Society Museum’s small but spectacular collection of Asian antiquities. It has subsequently been added to by a small number of gifts and acquisitions that adhere to the museum’s standards of excellence.

Fifty objects from the collection are currently on display at the Masterpieces from the Asia Society Museum Collection (until 7 January 2018) exhibition in New York. The masterpieces featured in this exhibition include ceramics, metalwork and stone carvings from Southeast, East and South Asia. The Rockefeller’s collecting strategy was motivated not by region or medium, but by how exceptional the pieces were. Be it a Chinese porcelain or a Khmer sculpture, the object had to be the most accomplished and refined of its type available at the time. Rockefeller’s rationale for collecting in this manner was that he believed exposure to examples of the most sophisticated Asian art and culture would lead to a better understanding of Asia and enable people to interact in a more informed way when conducting business and politics. As a result, the collection represents ‘the artistic pinnacles of the cultures that produced them.’

For me, the most important aspect of this exhibition is not the objects themselves – magnificent as they are – but the questions it poses to the audience about the collection and display of cultural heritage, and the role of museums in transmitting knowledge about the acquisition and provenance of these objects. As the international community witnesses the looting and destruction of cultural heritage in the Middle East, such questions are now more important than ever.

Visitors are welcomed to the Masterpieces exhibition by four Buddha heads placed in the entrance gallery, one of which is pictured below.

Head of Buddha. Indonesia, Central Java. 9th century. Asia Society, New York. 1979. Photo: Natali Pearson

The prevalence of these disembodied heads (and of headless statues) in museum collections remind visitors that these objects have often not survived intact over long periods of time, and that, whatever the circumstances of their dismemberment, they have been removed from their place of origin and have experienced further dislocation from their original context in the process.

There is a reason we often see such features – not only heads, but also hands and feet – dislocated from the original sculpture: whether removed with permission or stolen, these objects are more expedient to remove and transport than an entire statue. Heads of such sculptures in particular, with their curving lips and curled hair, often feature some of the most refined representations of artistic achievement. Hands and fingers arranged in a mudra (a religiously symbolic gesture), or the profound meaning attributed to the Buddha’s feet and footprint, make an equally strong claim for significance.

Inside the main gallery, the Masterpieces exhibition is divided into three parts. The first section, ‘For Sustenance in This World and the Next’, features works from China, Korea and Japan. These are objects used for holding food and drinks in domestic, imperial and ritual settings. The second section, ‘Regarding Gods and Kings’, includes a number of Southeast Asian objects, in particular a number of elegant (and headless) Khmer statues.

Female Figure. Angkor period (802–1431), early 11th century. Cambodia. Sandstone (Baphuon style). Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.65. Photo: Natali Pearson

The final section, ‘Transmission of Buddhism’, features various beings from the different streams of Buddhism, exemplifying ‘the complexity of the representation of Buddhist deities among these traditions across Asia.’ One of the most stunning objects in this section, indeed in the whole exhibition, is a fully intact 8th century bronze cast image of the Bodhisattva Maitreya (the future Buddha) from Thailand’s Buriram province. Every detail is impeccably rendered, from the smudge of his navel to the precise placing of each of his four arms.

Bodhisattva Maitreya. 8th century. Thailand, Buriram Province, Prasat Hin Khao Plai Bat II. Copper alloy with inlays of silver and black stone. Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.63. Photo: Natali Pearson

Bodhisattva Maitreya. 8th century. Thailand, Buriram Province, Prasat Hin Khao Plai Bat II. Copper alloy with inlays of silver and black stone. Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.63. Photo: Natali Pearson

Exiting the main gallery and re-emerging again in the foyer among the four Buddha heads, two large wall panels become apparent. Such wall panels, usually dense with text, are one method that museums use to communicate with their audiences. What is left out, such as the issue of provenance (where it is from and how it came to be in the museum’s collection), is just as telling as what is included, particularly with the smaller textual information displays used for specific objects.

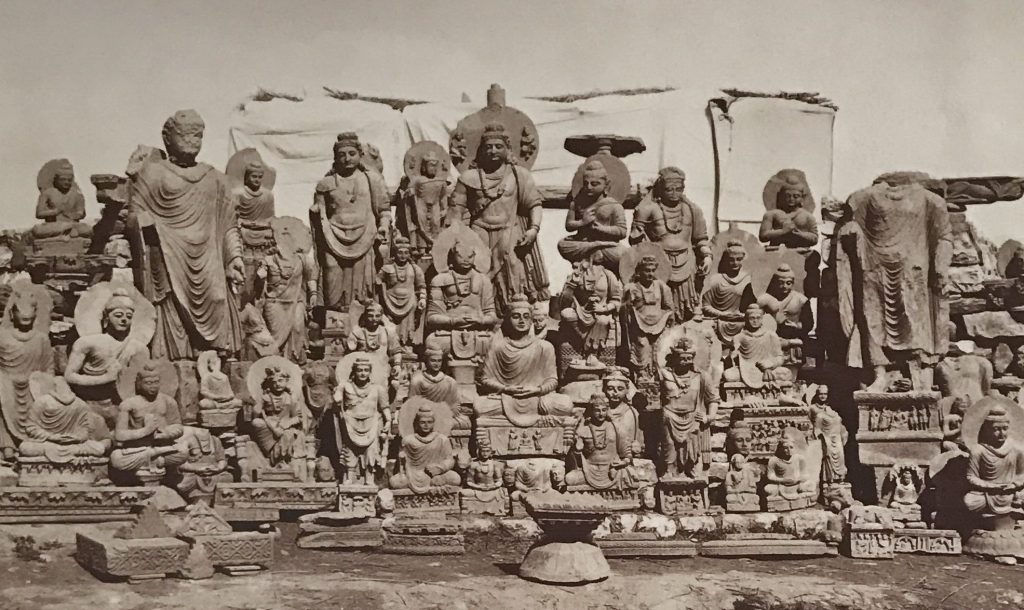

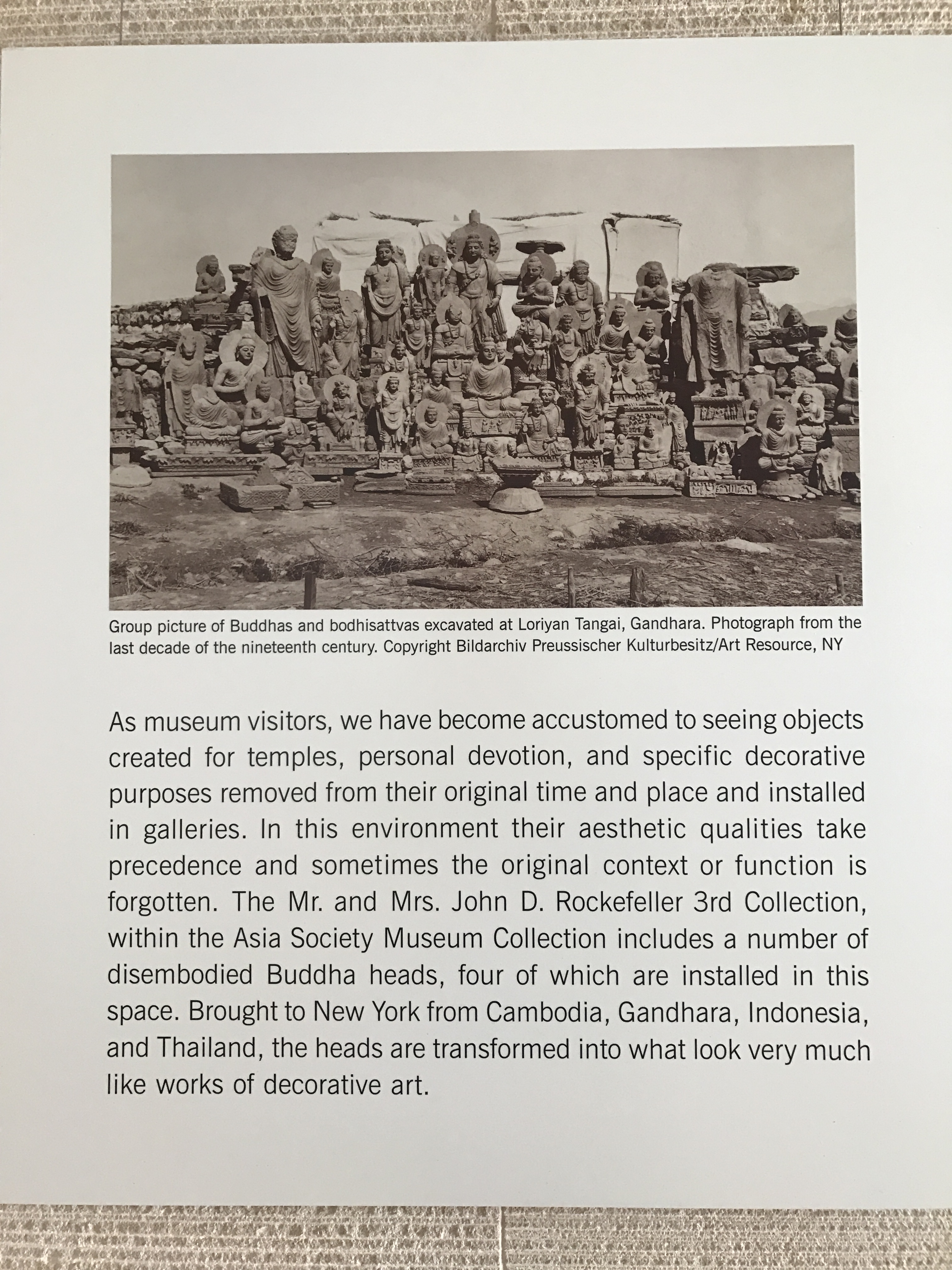

Rather than presenting a wall of educative text, these two panels offer both a photo and a list of questions. The photo is from the 19th century, and shows ancient Buddhist sculptures from Gandhara excavated by the British during their rule in India. The sculptures are assembled as if for sale, ready to be plucked out by the discerning buyer. Many sculptures or sculptural fragments like those shown in the photo are now on display in museums throughout the world – including as part of the Asia Society Museum Collection.

As museum visitors, we have become accustomed to seeing objects created for temples, personal devotion, and specific decorative purposes removed from their original time and place and installed in galleries. In this environment their aesthetic qualities take precedence and sometimes the original context or function is forgotten.

Wall panel, Masterpieces from the Asia Society Museum Collection, Asia Society Museum New York. Photo: Natali Pearson

Visitors to this exhibition are encouraged to engage more closely with the objects and the exhibition, and to reflect on the issues that collections of antiquities present to us – such as provenance, ownership, stewardship and restitution – as modern consumers of heritage.

Should museums worldwide collect and exhibit original artworks from other countries?

During times of political strife, if works of art are under threat of destruction in their home countries, should museums in other countries play a role as a safe haven for them?

Who bears the responsibility for the world’s cultural heritage and why does it matter?

Such questions can be understood within the broader context of international efforts to safeguard cultural heritage, particularly in light of the destruction of archaeological sites in Iraq, Syria, Libya and Yemen.

At the same time, a number of websites and organisations aimed at safeguarding cultural heritage – such as Chasing Aphrodite, Trafficking Culture and the Antiquities Coalition – have been increasing their calls for museums and galleries to be more transparent in their dealings, by sharing information about past and current collecting policies and the provenance of items in their collections. In Australia, the establishment of the Asian Art Provenance Project at the National Gallery is one example of the efforts that museums are making to keep pace with international and community expectations.

Greater transparency of museum collections is critical in a world where cultural heritage is threatened by looting, destruction and illicit trafficking. But in the push for greater scrutiny, many museums, including Asia Society, have found themselves cast as villains rather than allies in the effort to protect and preserve cultural heritage.

Asia Society’s efforts to communicate information about its collection have been proactive, and in fact pre-date the recent publicity about art theft and antiquities looting. For years, the entire permanent collection has been made available through publications and the Asia Society’s website, including, most recently, an online collection site that includes 3D imaging. When then Museum Director Vishakha Desai (1990-2004) received proof of the presence of a stolen 11th century sculpture from Rajasthan in the Rockefeller Collection, the sculpture was returned to India.

In 2016, Nancy Wiener was arrested and charged with conspiracy, accused of using her prestigious antiquities gallery to buy, smuggle, launder and sell millions of dollars worth of illegally-acquired Asian antiquities through leading auction houses. Chasing Aphrodite (‘The hunt for looted antiquities in the World’s Museums’) listed Asia Society as one of numerous cultural institutions that had possibly acquired objects from Nancy Wiener. But the inclusion of Asia Society on this list was incorrect: Asia Society has never purchased, or acquired in any other way, objects from Nancy Wiener.

When Dr Adriana Proser, Asia Society’s John H. Foster Senior Curator for Traditional Asian Art, considers objects for possible acquisition, she and her colleagues undertake a review of provenance documentation as part of their due diligence. Asia Society’s acquisitions policy is in line with the ethical standards taken by the Association of Art Museum Directors and the American Alliance of Museums, and the Collections Committee does not consider acquisition of objects without proper documentation.

Asia Society has also established the Asia Arts and Museum Network, Transfuze, one of the central themes of which is the preservation of culture. In 2015, Asia Society held the Arts & Museum Summit in Hong Kong, which focused on issues of cultural heritage preservation and protection in Asia. Asia Society Museum has subsequently published Assuring our Cultural Legacy in the 21st Century, an edited collection of essays that consider the key ethical and practical questions facing preservation and cultural heritage. Asia Society also holds regular public seminars about topical issues such as ethical collecting practices.

For centuries, museums have safeguarded much of the world’s cultural heritage, acting as keepers and protectors of unique, fragile and significant objects. Over time, their role has evolved from 17th and 18th century notions of ‘cabinets of curiosities’, in which cultural heritage was something to be acquired and questions of ownership were very much secondary, to a far more inclusive approach that embraces education, access and research, and rejects the complicity of (often colonial) collecting practices.

As this evolution continues, museums are being asked to forge new ground in how they manage, present and even justify their collections to an increasingly concerned public. It is no longer enough for a museum to argue that the collection is a historical legacy, or to claim that the museum, as a modern-day keeper of the collection, is not morally responsible for the collecting decisions made by the institution’s forebears who operated in a different legal and ethical context.

The movement to identify and repatriate looted objects is a critical part of this evolution, and is well overdue. However, as public awareness about stolen antiquities grows, we need to ensure there is also a space for museums in this conversation, and that they are not automatically dismissed as unwilling participants in discussions about ownership and provenance of cultural heritage. Efforts to undertake and share due diligence of collections should be recognised, and the repatriation of stolen antiquities should be welcomed, particularly when a museum has been proactive in doing so.

Nor are museums the only ones with a role to play. It is critical that we also consider the role that we, the general public, have, in terms of our expectations, understandings and assumptions of how heritage is, and should be, managed.

We should expect, for example, information to be publicly available about provenance, whether it is in publications, online or via object labels in the gallery. We should also expect museums to return objects that are known to have been illegally acquired. More broadly, we should reflect on the questions posed in Asia Society’s Masterpieces exhibition. Should museums worldwide collect and exhibit objects that originate from other cultures and countries? If objects are under threat of destruction in their home countries, should museums in other countries play a role as a safe haven for them? Who determines when it is safe enough to return them?

There are no easy answers to any of these questions, except for the last one: who bears responsibility for the world’s cultural heritage? We all do.

***

Disclosure: Natali interned for Asia Society Museum in 2013 and continues to work as a consultant to the biennial Asia Society Arts & Museum Summit.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss