Christine Gray examines new sites of symbolic battle after King Bhumibol’s death.

Previously the Thai junta focused on all things remotely royal in its quest to repress dissent. Fierce generals ventured into Facebook, redolent of social fluff and immaturity, to enforce Thailand’s ridiculously ill-defined and hence terrifyingly effective lese majeste laws.

In the present Funerary Era of the interregnum, that quest has since been extended into the realms of Youtube, Line and Twitter, relentlessly expanding Thailand’s great ‘firewall’, tightening the noose of royal censorship.

From the farang or foreign perspective, the most incomprehensible and ridiculous points of conflict were indirect insults to the King by way of Facebook commentary on his beloved dog, Thongdaeng.

The sacred Thai-Buddhist “language of images” is a “high” form of communication, including royal rituals, bike rallies even, that has been tirelessly re-worked and re-invented by His Majesty and the royal handlers. From the standpoint of the Thai elite, satire about Thongdaeng was an infuriatingly inventive “low” form of communication, employed by commoners, students, factory workers and the like, expanded to encompass language and images, cartoons and emojis.

Re-visiting photos of His Majesty and Thongdaeng, one can see why commentaries on Bhumibol’s beloved pet would constitute such insult. The pair displayed a genuine bond of affection that was rarely witnessed between His Majesty and members of his immediate family, particularly Crown Prince Maha Vajiralongkorn after the latter embarked on his lengthy and harrowing career as an adult.

One reason the warm bond that existed between Thongdaeng and the late King was rarely witnessed between Bhumibol and his other nearest and dearest was because photos of the latter in the late 20th century tended mainly toward their performance of state ritual as opposed to informal shots of the family when the children were young.

Portrayal of the Thai Royal Family as ordinary, middle-class folk to their subjects — or, more critically, to key British and American audiences — was entirely in the style of the British throne. This served as the model for the Thai monarchy beginning in the reign of the modern, scientific King Mongkut (1851-1868), or Rama IV.

This area of cultural invention, spectacularly elaborated upon by his son King Chulalongkorn, Rama V, arose from constraints of colonial and post-colonial rule — that is, the necessity for Thai rulers and their people to appear “civilised” in order to remain “free” from foreign intervention and subjugation.

More to the point, the proper visage of a genuine Buddhist king is one of compassion and impassivity, demonstrating detachment from worldly things in the style of the Buddha or a future Buddha (bodhisatta) — the official belief about King Bhumibol in this next stage of his deification or “passage to the Buddhist heavens” (sawannakhot).

Portrayals of warm bonds between Their Majesties and the royal grandchildren proved even more problematic given the crown prince’s sexual and marital inclinations. Upon which grandchildren should they shower their affection?

Would it be the camera-ready daughters of the Crown Prince by wives number one and number two, featured in last year’s heart-warming, family-friendly Bike4Dad event?

Would it be far less camera-ready Prince Dipangkorn, who was clearly in line for the throne until signs of autism or a related disorder became painfully apparent?

For this and related crimes, the prince had Dipangkorn’s mother, the beautiful and deferential Princess-Consort Srirasmi, disappeared, her family imprisoned for improper use of the prince’s name in their/his business dealings.

Would it be the four handsome, accomplished sons by wife number two, abandoned by the Crown Prince, exiled and educated in the United States?

Or might it be the latest son (anon) by consort-wife number four, Suthida Vajiralongkorn na Ayutthaya, Commander of the Crown Prince’s Division of the Royal Guards?

This sixth son may be invisible, but his mother is certainly coming into public view.

Decked out in the red, the full dress uniform of the Royal Guards (or the King’s Own Guard), Suthida was photographed in the front seat of the unmarked van bearing the Crown Prince in the anonymous yet somehow royal convoy transporting the King’s body to the Grand Palace on Friday, 14 October.

Military appointments and the awarding of state honours are state and/or royal prerogatives par excellence.

Flexing his clout in the same way he had promoted his and Srirasmi’s beloved poodle Foo-Foo (b. 1997, d. 2015) to the rank of Air Chief Marshal in the Royal Thai Air Force — the same rank held by wife number two’s alleged lover — the Crown Prince promoted Suthida to the rank of Lieutenant General in the Household Guards, the means by which she is edging herself (or being edged) into the Royal Family.

Around the same time, she was awarded Thailand’s highest female order (Dame Grand Cordon) of the ancient orders of the White Elephant and the Crown of Thailand. The former air hostess was thus catapulted into the rarified company of such luminaries as former Thai dictator Phibun Songkram, Sultan Ibrahim of Johor, The Earl Mountbatten of Burma, and General William Westmoreland.

These orders situate her at the outer, ambiguous edges of the royal family, enjoying roughly the same status as the non-royal daughters of Vajiralongkorn’s older sister Ubonrat, who lost her treasured cao fa (celestial princess) status when she married an American, a sin which her father found hard to forgive.

Since the Royal Household Guard was created by the 15-year-old Chulalongkorn as the King’s Own Guard, a means of cordoning off his inner-circle from his business-minded Bunnag regent, such designations carry interesting, ambiguous meaning, Thai kings and princes being able to switch up such titles at will.

The military, too, is doing its part in this unprecedented time of grief.

To deflect attention away from the succession, the junta has focused its efforts on the proper etiquette of mourning — improper displays (or total lack thereof) having become the focal point of the nation’s protean, fast-moving lese majeste laws. At the same time, they are sanctimoniously forgiving the violence that has become a hallmark of the new era of mourning.

As part of the effort to structure and limit knowledge and information, they have chastised the BBC and other high-profile Western news outlets for improper reporting. Like outrage over improper reference to the King’s dog, some of these constraints or criticisms may appear nonsensical to the West. They are not.

In the case of the BBC, whose programming is occasionally, arbitrarily interrupted for supposed insults to the Crown and the Thai people, this censorship serves two purposes.

BBC’s alleged error was underreporting the fantastical numbers of loyal citizens “flocking” to Sanam Luang, the Royal Parade Grounds, to witness the passing of the King’s body from Siriraj Hospital to the Grand Palace, there to undergo ancient funerary rites that commenced with the symbolic bathing of the royal corpse.

Vast numbers of anonymous subjects flocking to witness the splendour of the Dhammaraja or Righteous Ruler, ordinary mortals stunned and subdued by the King’s merit, are themes and images embedded in Thai Buddhist art and cosmology.

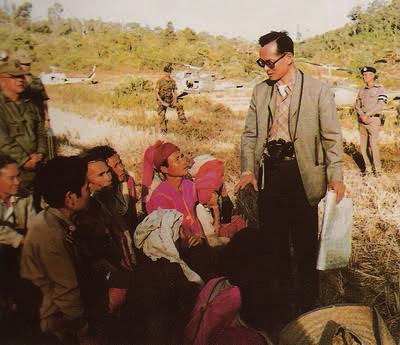

They are also central to the hagiography of the Ninth Reign as demonstrated by the energy, forbearance, gentleness, rectitude, and self-sacrifice of King Bhumibol in His Majesty’s forays into the rebellious periphery of his kingdom to see to the well-being of his less enlightened subjects. These presentations and historical moments, copiously captured on camera and promoted internationally, are structured as embodiments of the thotsaphiratchatam or Ten Kingly Virtues of the great Buddhist monarch.

His Majesty’s great virtue or barami aside, said subjects — hill tribesmen, peasants from the Northeast and the like — sometimes had to be paid or otherwise motivated to attend such events.

Swiftly inducted into matters of proper etiquette (like prostration), His Majesty’s less civilised subjects thus displayed the requisite interest and attention as the King, by virtue of his superior knowledge and wisdom, dispensed advice as to how they could better conduct their affairs.

Despite the above, disinterest in His Majesty’s “passing to heaven” is reported as being present if not prevalent in remote areas of Isan, the Northeast, over the last week, with the exception of government officials.

In the late 1970s, when I conducted field research on the kathin ritual, Isan remained populated with communists (kommunit) or “suspected communists,” so much so that the discovery and rooting out of such could be characterised as a lucrative cottage industry for Thai police.

This was doubly true of the Thai Border Patrol in Chiang Mai and regions north. The border police came under the patronage of His Majesty’s late, saintly mother after Police General Phao Sriyanond, no admirer of royalty, had been driven from the country in the pro-royalist Sarit coup of 1957.

A new generation of police generals thus became magically, discretely wealthy from the “suppression” of the narcotics trade in tandem with the rooting out of communists, bandits, Chinese merchants, bankers and other people associated with the Golden Triangle.

During this period, discovery of communists and other varieties of dissidents was necessary to attract unreal amounts of US aid. This included both military aid — Thai officers sported state-of-the-art walkie-talkies, using them to direct subordinates in the ordering of dinner at hotels, even — and for the modernisation and national development plans embodied in and spearheaded by the activities of the Buddhist Righteous Ruler.

Some of His Majesty’s Isan subjects were quite cynical about the monetary sources of the King’s virtue, particularly after they discovered that His Majesty’s beneficence was funded, in part or in whole, by their own tax money, which they figured they could put to better use.

Before the rise of the socialist movement, initiated by the brilliant legal scholar and Senior Statesman Pridi Phanomyong (1900-1983), who fled into exile in China and then France for supposed involvement in the as yet unexplained death of King Bhumibol’s older brother, King Ananda — carried on into the 1960s and 1970s by the stubborn, brilliant and uppity Isan monk Phra Phimonlatham (b. 1903, d. 1989), who promoted a rival version of world peace — the King’s rural subjects, more inclined than His Majesty towards superstition, supposedly believed that such beneficence “fell from the sky,” the magical accumulation of wealth being a prime feature of the Maha Cakkavatti, the Great Wheel-rolling or Universal Monarch of Buddhist mythology.

A key question and point of contention now is, who is going to pay for the late King’s magnificent funerary displays? The state, the King’s personal fortune, or the Crown Property Bureau? Indeed, how would one even know?

The other point of seemingly arbitrary displays of state power directed at the BBC and other foreign news outlets is simply to reinforce messages about the absolute powers of the state, and to force journalists back, thereby providing the royals, the military and the police a circle of privacy and anonymity in which to work their magic — divvying up power and resources once again while presenting the appearance of national harmony via hysteric expressions of grief.

“Unity,” khwam samakhi, indexes the virtue of a great Buddhist king. Khwam samahki is thus the supposed defining feature of King Bhumibol and the Ninth Reign in pursuit of the now-antiquated goals of national development.

Heart-warming deference to his father as demonstrated by the Crown Prince in last year’s stupendous Bike4Dad event, sponsored by Prayuth and his government, resplendent grief as demonstrated by the Crown Prince in the performance of his funerary duties in the first week after his father’s death, insure the sanctification of the late King. They also reinforces the whopping case of national and international amnesia that goes with; the link of the Crown Prince to his father; and the all-important transmission of lineage, which only occurs male to male.

Any proper ruler, be it Queen Elizabeth or a Buddhist king-deity, has both a public, ritual body and a private body, separating their divine and human selves.

The Crown Prince, as he takes the field, has chosen funerary rites for expression of both.

At any rate, proper mourning, in the realms of virtual reality or its pale opposite, is the new Thongdaeng.

One should never underestimate the Thai public’s capacity for satire as deference, however, given their long and fruitful experience of monarchy.

As a Buddhist adept said of the enforced wearing of black, “It’s simpler.”

Should the picture become too bleak, the ritual order dissolve, as it appears to be doing, and the violence increase beyond the sporadic, these developments could reasonably be construed as lang hayana, “signs of doom and gloom,” in accordance with Buddhist beliefs about anicca or impermanence, signaling decline of kingdom and cosmos.

That, too, would be totally within the bounds of Buddhist cosmology.

Thongdaeng may have reeked of satire, in both Thai and Western domains, but the King’s death does not, even remotely.

The kingdom fades to black.

Christine Gray, PhD, is a cultural anthropologist who writes about monarchy, ritual, gender and power.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss