Rianne Subijanto analyses Indonesia’s presidential campaign and interrogates what the would-be presidents are trying to tell us.

In Indonesia’s upcoming presidential election, the campaigns of the two candidates are characterised by two strikingly different communication strategies. A close examination of their respective media campaigns and mission statements–visi misi–reveals those strategies, strategies which reflect the living historical struggles existing in Indonesian society, sixteen years after the overthrow of Soeharto’s dictatorship.

Prabowo’s campaign has been built around the idea of a strong leader. He does this in a strange mash-up of two leadership styles. Visually, he adopts the body of Sukarno, but in language, he imitates Suharto. For instance, Prabowo pronounces the suffix kan as ken, such as in the words mengandalken and inginken, which reminds us of Soeharto’s style. We are aware that both presidents had a history of top-down leadership–Soekarno’s guided democracy and Soeharto’s New Order. In this case, the myths of a “strong leader” from both presidents are imitated and combined.

In the 1970s, President Suharto rolled out agricultural reforms that successfully achieved rice self-sufficiency. Here he waves a sheaf of padi next to wife Ibu Tien.

The focus on building a “strong leader” image appeals to the segment of Indonesians who still believe in the coming of ratu adil (lit: “just king”–a messianic figure) who will solve the nation’s complex problems.

Prabowo plays on the ratu adil trope in his use of visual aesthetics in his campaign ads on television, which bear a remarkable resemblance to the aesthetics of Soeharto’s New Order regime.

The first technique is by building a narcissistic persona, the “I”. Watch a few of Prabowo’s TV ads and you will notice that almost all of his party ads are dominated by himself, in image, activity and voice. The portrayal of the people and their activities–as a farmer, teacher, fisherman–only background the persona of their coming savior.

The second technique is the camera angle and the voice-over that give a sense of impersonal viewing as if we are there to witness Prabowo but not involved in the event. The creation of this distance functions to build the character of a “sacred” leader who descends from heaven and whose place therefore is above the common people.

The ‘need’ for this type of leader is adopted and reciprocated by Prabowo’s supporters, seen in a song by singer, Ahmad Dhani:

“We need a strong leader

we need a firm leader

who can bring this nation to be number one.

Now or not at all

…

This is our only opportunity to be

A nation that is big and feared

A nation that is respected”

[Prabowo’s voice] “if not now, then when?”

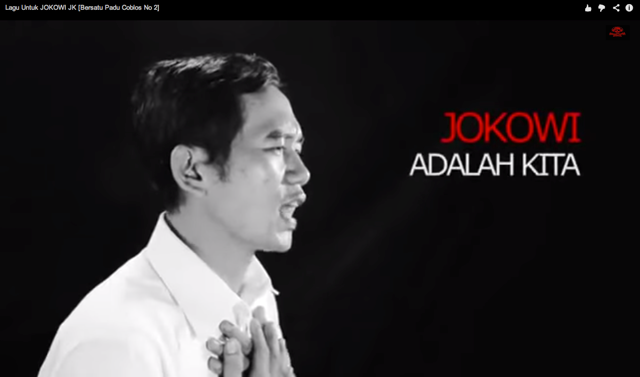

By contrast Jokowi’s ads focus on “community building”. Jokowi’s TV campaign tries to build a sense of inclusiveness with the viewers. The ads do not center around Jokowi’s character–hence no individual photographs–but instead around Indonesian people themselves.

Jokowi’s campaign advertisement doesn’t even feature him because as the slogan reads “Jokowi is us”.

The camera angle takes a position for a horizontal viewing. Kita “we” is repeated in the advertisement voice-overs, for example:

“We want an honest leader

We want a clean leader

We want a simple leader

but

are we ready to be led to be honest?

are we ready to be led to be clean?

are we ready to be led to be simple?

Together with a leader born from the people?

We are ready to become the real Indonesia.

Jokowi-JK is us.”

The use of the word “we” extends an inclusive hand to viewers, opening up cooperation and communication.

How does the candidate imagine us, the people? And how does he plan to communicate with us? For this, I turn to their mission statements.

Let’s think about how Prabowo talks: What words does he use? In his mission statement he uses the word rakyat (the people) 23 times, bangsa(nation) 11 times, and publik (public) once. The use of rakyat is interesting, as it means the “the mass”, “the commoners” and “lower people” (KBBI, 2005).

However, rakyat comes loaded with political connotations. Notice how rakyat in Prabowo’s mission statement is used in the following contexts: to support the rakyat’s interest he holds a program that is “pro-rakyat”; to apply populist economic principles, he puts the agenda of “ekonomi kerakyatan”. This reflects the word’s connotations, that it: 1) assumes that rakyat is a passive mass, and 2) it builds a hierarchical relationship between the leader and the people.

Soeharto relied on a similar patriarchal and an infantisation of the people. Notice the following quote from a song Bapak Kami Soeharto” (“Our Father Soeharto”) popular in early 1990s (I sang this song in a choir as a girl scout when Soeharto opened the 1996 National Jamboree):

“A father whom You love

To lead our beloved country

His charisma and smile

Gave cheer to Indonesia’s face

To you our father Soeharto

Thank you from rakyat all

In our hearts we uphold

The father of Indonesia’s development”

How about Prabowo’s communication plan? I can’t find any specific communication program in his statement besides–copying the previous governments’ model–perceiving communication as an instrument for the economic development project (point I.5, I.8.b, II.6.8., VI.2, and VI.6).

This instrumentalist view of communication implies an instrumentalist view of the people.

Jokowi, however, uses the concept of the “public sphere” in his communication plan to assert his commitment to democratization.

In his 41-page mission statement, the word bangsa (nation) (51 times) and publik (public) (41 times) are the two most frequently used words, compared to rakyat (at just 14 times), to refer to the citizenry.

The concept of publik is often contrasted with that of mass (rakyat). The public are active citizens, involved in shaping opinions and attitudes to criticize and direct state affairs, while the mass (rakyat) are assumed to be passive followers.

For rakyat, political opinions are handed down by leaders, but the opinions of a publik are crucial in shaping state affairs. How then does Jokowi propose to channel the opinions of the publik into statemaking?

Jokowi’s plans for “public communication” are explained on page 17, 24 and 25 of his mission statements. The details include public access to and transparency of information, eliminating the current monopoly on broadcasting ownership and developing a domestic industry for information technology.

One point deserving highlight is: “we will provide a forum to involve the people in the legislative process and provide access to the legislative process and its products”.

Prabowo’s use of traditional techniques in persuasion and Jokowi’s new style are also reflected in the presidential debates.

Prabowo’s style follows textbook guidelines for oral rhetoric: simplicity and repetition. For the questions ranging from corruption, national economy, female mortality, national security, budgeting, trade deficit and foreign relation, his main answer is “bocor” (leak). In all three debates, bocor was used 25 times and in several occasions he said it in repetition “tutup kebocoran, tutup kebocoran, tutup kebocoran” (stop the leak). In his view, because the national wealth is leaking to foreign investors/countries, we do not have sufficient economic resources to solve those national problems.

In this case, bocor is a metonym for Prabowo’s populist economic program.

Jokowi’s technique is less traditional. His statements often demonstrate obvious pre-prepared answers, which seem less spontaneous for a debate. While his answers are more nuanced, he often resorts to managerial problem solving by walking the audience through the process–hence the use of acronyms and emphasis on bureaucracy which are the areas he masters as a governor. He does not use a particular expression repetitively. Even his slogan “revolusi mental” (“mental revolution”) was only used five times in the first three debating events.

Why was Prabowo–portrayed as a “strong, firm leader”–going soft half way through and stressing agreement in the last two debates? And, why did Jokowi begin to shift from a slight meandering style to a more decisive one?

There are two answers for Prabowo’s case. First, going soft helps allay people’s prejudice against Prabowo’s (bloody) military background. The glorification of Prabowo as a strong leader in his campaign–despite taking advantage of his background–starts to backfire him when data on his human rights abuse resurface. People start to liken him with a dictator and define tegas (firm) as “kejam” (“cruel”). For this reason, it is tactical for Prabowo to tone down his aggressive style.

Similarly, stressing agreement is effective in eliciting sympathetic feeling from the audience especially when you know that you are losing the debate. Prabowo did this several times in the second and third debates. For example, instead of giving a rebuttal to Jokowi’s data-driven answer on creative economy, Prabowo stood up and said that while he was advised never to agree, “I am not a professional politician, I do not want to listen to my advisors. So I concur with Joko Widodo [walking toward Jokowi to shake hands]”. Prabowo’s “bocor” theory seems to limit him and so it’s a strategic move to express agreement.

Remember the classic saying: “if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em!”

In Prabowo campaign’s glorification of a strong, firm leader, Jokowi is portrayed as a ‘weak’ leader–the puppet of elites. In the third presidential debate Jokowi took the chance to rebut this by raising his voice and asserting, “Don’t think I cannot be firm (tegas). Firm in my opinion is to be brave to make a decision and [to take] the risk.”

While the contrast of both candidates’ oral rhetoric styles is striking, it is obvious that Prabowo–with his traditional textbook approach–tends to utilize emotional persuasive appeals and Jokowi has a propensity to use more cognitive persuasive appeals.

The art of persuasion is to know one’s audience and feed into what they desire. Prabowo’s style centering around the development of the myth of a strong leader”–the “I”; treating the people as rakyat (mass); and, speaking to appeal to emotion rather than thinking seems to represent residual modes of persuasion passed from Soeharto’s regime and brought back to life in the current election.

On the other hand, Jokowi’s style focusing on community-building–the “we”; positioning himself horizontally with the people as publik; and, speaking in a manner that appeals to our cerebral self reflects an emergent alternative mode. He is the child of Indonesia’s reform era and he speaks like it.

With the polling gap getting closer, both candidates’ communication styles seem to have their appeal. In less than a week, we will witness which route Indonesia elects to take.

Rianne Subijanto is a doctoral candidate in Journalism and Mass Communication at University of Colorado Boulder and an editor of indoprogress.com.

This is an updated version of an article originally published in Indonesian entitled “Antara “rakyat” dan “Publik””. The original can be found at indoprogress.com.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss