This article is being published as a matter of urgency to serve as a basic introduction to the subject of minority rights and mapping of ethnolinguistic groups. The need is even more pressing, given the critical juncture in Thailand’s history where the interim military government seems intent on imposing a highly repressive, authoritarian, and nationalistic model on Thai citizens. This column also seeks to re-host the Ethnolinguistic Map Project of Mahidol University (MU), Thailand’s best data source on minorities.

Thongchai Winichakul’s Siam Mapped: A History of the Geobody of a Nation is on the essential reading list of any Thai studies student. Published in 1988, it explains the increasing relevance of maps and concomitant delineation of borders to the Siamese polity from the pre-modern period to the 20th century. The text also comments on Thailand’s discourse of pan-Thaism and the rhetoric of territory lost which has defined Thai nationalism or “Thainess” – a discourse currently being revived via Thailand’s reform forums, which feature a video cataloguing the “loss” of 14 territories (other versions here and here) by the Thai state, including eight territories examined by Thongchai but also including, most recently, the “loss” of Khao Phra Wihan to Cambodia.

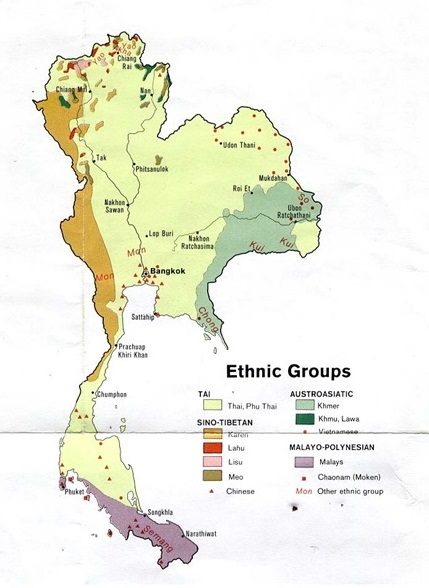

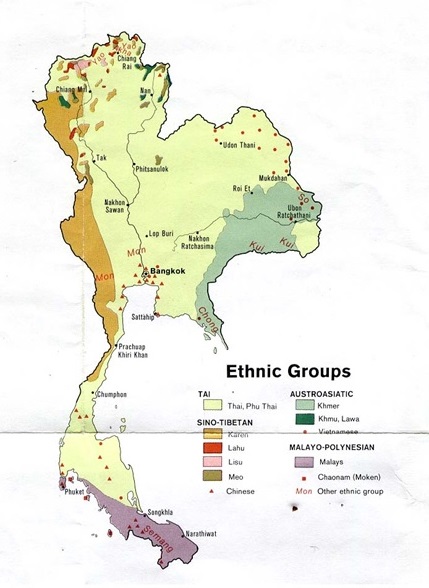

For many observers of modern Thailand, one of the most significant and probably best known map of ethnicities is this one, sourced to the Central Intelligence Agency:

Courtesy Library of the University of Texas

This map is indicative of the “ideal composition” of the ethnic groups of Thailand from the point of view of Thai authorities, and the authorship and date indicate it to be a product of Cold War thinking. Of particular note, the Thai Lao and Khon Mueang are wholly subsumed into the Tai family and are not separately delineated or mentioned. Furthermore, ethnic groups are not specified in detail. This map is the typical one regarding ethnolinguistics used on Wikipedia. Nonetheless, this map is an advance on the 1939-1944 period, when the hyper-nationalist dictator Field Marshall Pibul Songgkram, building on previous thinking from the turn of the century, eradicated recognition of Thai minority identities by decree in the course of his State Cultural Mandates (particularly Mandates 1, 3, and 9).[1]

This kind of map informed and described Thai national thinking on Thailand’s ethnic groups until the 1990s. By 1995, Thai academics in the field of linguistics, championed by Mahidol University’s Institute for Language and Culture for Rural Development (ILCRD), founded in 1981and moved to the MU Language and Culture Building under the patronage of HRH Princess Sirindhorn (now renamed and part of the Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia [RILCA]), were publishing papers detailing Thailand’s minorities in academic journals and were beginning to use the term “Lao Isan.”[2] As such, they introduced normative principles for linguistic, ethnolinguistic, and sociolinguistic investigation of minorities and language-related issues in Thailand which questioned the state-sponsored picture of an ethnically homogenous Thailand.

This development was influenced by increasing dialogue with supranational organizations such as UNESCO and UNICEF, responsible for maintaining numerous treaties involving minority rights; by contact with the faith-based and missionary-connected Summer Institute of Linguistics, which maintains the Ethnologue database; and by interaction with international scholars through increasing personal contacts at international conferences. This period was epitomized by the publication of the William A. Smalley’s 1994 hierarchical arrangement of minority languages in Linguistic diversity and national unity: Language ecology in Thailand, which has become a standard bearer for Thai studies (but interestingly, never translated into Thai). For the first time in nearly a century, the six million Khon Mueang and 15 million Thai Lao were recognized as ethnically separate from, though related to, Central Thais, in publications available in Thailand.

The pinnacle of this development pathway was the Ethnolinguistic Map Project undertaken by Mahidol University’s ILCRD, described in English here and in Thai here. This mapping project identified practically all the ethnolinguistic groups in Thailand through systematic randomized surveying as well as a systematic review of the literature. It provided both a map of Thailand’s minorities and revealed Thailand to be a pluralistic, heterogeneous polity and was published in 2004-2005.[3]

However, the publication received a limited print run from the Office of the National Culture Commission and could only be accessed electronically at the Bangkok ILCRD location, though the intention to put the project online is evident from the Project website. Nonetheless, data from the project found its way into documents submitted to UN agencies, such as the 2011 report to the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination under the UN International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. The potential of the Ethnolinguistic Map Project data can be seen in these two Ethnologue summary maps of the ethnolinguistic groups of Thailand, though on the Northern Thailand map, both the Thai Lao and Khon Meuang have been reduced to the status of regional dialects of Thai.

The mid-2000s was the same time as Thai institutions spearheaded by MU and assisted by UN agencies such as UNESCO and UNICEF began promoting the “Mahidol Model” of dual language education in the Deep South. It was also at this time that the Royal Institute’s sponsorship of the Draft Thai National Language Policy began to be promoted at international conferences and was publicly endorsed by former Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva in 2010 and former Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra in 2011.

The authors of this article would be interested in any information regarding whether any online, internationally available mirrors of this database exist.

The importance of this database is that it bridges the gap between, on the one hand, the international academic and public sphere and, on the other hand, the notably insular Thai academic and public sphere. It proves that international research of the highest standard could be conducted in Thailand on sensitive issues such as the linguistic and cultural rights of minorities in the North and Northeast, and it signifies that elements of Thai academia and society were prepared to endorse a pluralistic and multi-ethnic model of the Thai polity, reversing decades of hegemonic concentration of Thai nationalist branding through agencies such as the National Identity Board.

However, at present, due to a military intervention, Thailand faces an acute concentration of power in the hands of the few. “Thainess” has again been reformulated as a nationalistic monolith in the form of 12 cultural values directed from the center without any consultation or due process. The National Human Rights Commission faces abolition against all international principles and treaty obligations. Decentralization is paid lip service in the Draft Constitution, and there is little or no mention of minority rights in the same document, nor is there mention of organic laws on decentralization or on minority rights. Some of the implications of this mentality, one which encourages a variety of potential crimes against humanity including in heavily debated areas of jurisprudence such as cultural genocide, ethnocide, and linguicide, have been described in a recent Prachatai article sourced from an original Isaan Record column available here.

Via this New Mandala article, and in the spirit of international and open scholarship endorsed by the Ethnolinguistic Map Project website itself, the authors are again making the Ethnolinguistic Map Project available, using a series of copies of the maps in the form of a pdf, maintained by New Mandala and available here. If Mahidol University requests the removal of this resource, the authors will discuss the request in consultation with New Mandala. If the request to take down the source is successful and MU does not undertake to re-host the Project, the authors reserve the right to publicize this decision and will seek support for an international seminar on whether there is a moral obligation to host the Project outside of Thailand. Such a decision would remove a highly valuable database and represent a retrograde step from Thailand’s treaty commitments, for example, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity, and the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Thailand and its vast minorities deserve a better future.

John Draper is a project manager with the Isan Culture Maintenance and Revitalization Programme at the College of Local Administration at Khon Kaen University and writes for the Khon Kaen School.

David Streckfuss is an Honorary Fellow of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He is the author of ‘Truth on Trial in Thailand: Defamation, Treason, and lèse-majesté’ (Routledge, 2011).

Download ‘Ethnolinguistic Maps of Thailand’ here.

References

[1] For more on the Thai government’s attempts to mask the ethnically plural nature of populations within the country’s borders, see David Streckfuss, “An ‘ethnic’ reading of ‘Thai’ history in the twilight of the century-old Thai nationalist model,” Southeast Asia Research (special edition on the Northeast of Thailand) 20 (3), 2012, pp. 305-26.

[2] Suwilai Premsrirat, S. (1998). On language maintenance and language shift in minority languages of Thailand: A case study of So (Thavung). In K. Matsumara (Ed.), Studies in endangered languages: Papers from the International Symposium on endangered languages, Tokyo, November 18-20, 1995. Tokyo: Hituzi Syobo.

[3] See Suwilai Premsrirat et al. (2004). Ethnolinguistic mapping of Thailand and on going language revitalization programs. In Putting Cultural Diversity into Practice: Some Innovative Tools. Asia-Pacific Regional Training Workshop on Culture Mapping and Cultural Diversity Programming Lens to Safeguard Tangible and Intangible Cultural Expressions and Project Cultural Diversity. Training for Asia-Pacific Field Personnel. 15-18 November. UNESCO. Bangkok, Thailand: UNESCO.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss