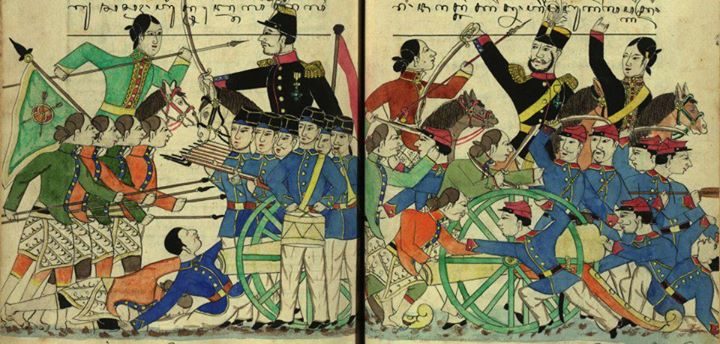

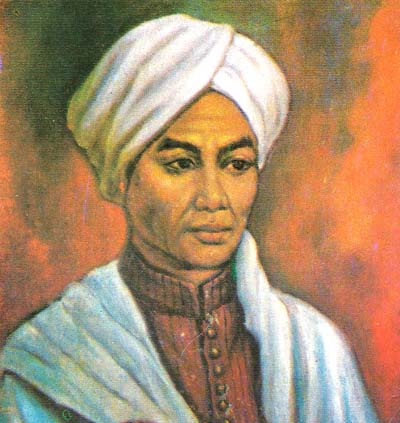

The Java War (1825-30) was led by Prince Diponogoro against the colonial Dutch. In popular narrative, the war marked the birth of Indonesian nationalism. Two of Prabowo’s ancestors sided with Diponogoro to fight in the Java war, forming part of the Prabowo’s campaign claims to the presidency.

I live between two countries both of which were former colonies: Ireland and Indonesia. The former was England’s first colony and the first in the twentieth century to escape its imperial thrall – initially as the Irish Free State (1922-37; post-1938, Eire), and then (from 1949) as an independent Republic.

The latter, the former Netherlands East Indies (1818-42; post-1945, Indonesia), has the dubious distinction of having been the most profitable colony in the world for its Dutch colonial masters: 832 million guilders or USD75 billion extracted as profit for the mother country in the forty years between 1830 and 1870 alone.

Both Ireland and Indonesia have an acute sense of their history. This has shaped their post-independence identity and generated ‘national histories’ based on a story of anti-colonial struggle.

While it is impossible to envisage a situation in which the current UK Prime Minister, David Cameron, might use the history of his family’s involvement in the Napoleonic Wars (1799-1815) as a reason for voters to choose his party, this is not the case in Ireland where the country is about to celebrate the centenary of the Easter Uprising (24-30 April 1916).

The last in a long line of ‘noble failures’, suicidal uprisings which marked modern Ireland’s three-century struggle against colonialism, this is bound to prove controversial as the emergence of ‘physical force’ Republicanism, which the Uprising seemingly legitimated, is not universally accepted.

When it came, Irish independence was forged in blood: the divisive civil war (1922-23), fought between pro- and anti-treaty forces over whether to accept British terms for an Irish Free State as laid out in the 6 December 1921 Anglo-Irish treaty, precipitated the principal division in post-independence politics pitting the pro-treaty Fine Gael (Tribe of the Irish) party against the anti-treaty Fianna F├бil (Warriors of the F├бl).

One of the leaders of the Uprising, ├Йamon de Valera (1882-1975), Fianna F├бil’s founder (1926), would become a key figure in the post-independence state, serving as President of the Executive Council (later Taosieach [prime minister]) (1932-42; 1951-4, 1957-9) and as President of Ireland (1959-73). Both his son and grandchildren would have distinguished political careers in post-War Ireland.

De Valera’s great – but tragic – political rival, Michael Collins (M├нche├бl ├У Coile├бin) (1890-1922), who negotiated the Anglo-Irish treaty and lost his life in an ambush during the civil war, hailed from an even more remarkable Republic dynasty. Referred to by the British Secret Service as ‘brainy’, the Collinses were a family of ‘over-achievers’. Part of an ancient Gaelic clan, widely spread over County Cork, their Republican connections could be traced back to the 1798 Rebellion in Ireland.

If one is looking for modern-day Indonesian equivalents to the De Valeras and Collinses, the Djojohadikusumo family is as good a place as any to start. Another ‘brainy’ family of over-achievers – high-born priyayi (officials; literally ‘para yayi’ – ‘younger brothers’ of the rulers) this time rather than ancient Gaelic tenant farmers – they have been prominent in the public life of Java for at least five generations since the Java War (1825-30).

Two immediate relatives of the current generation fought on Prince Diponegoro’s side during this war. The first, Tumenggung Banyakwide (Kertonegoro IV), as a junior commander; the second, Raden Mas Joyoprono (post-1832, Raden Tumenggung Djojodiningrat), as a soldier-administrator.

Both would pay a high price for their involvement. The first was exiled to Ternate for refusing to lay down his arms after Diponegoro’s capture and the latter suffered war wounds which left him permanently disabled.

Both would eventually become district administrators (bupati): the first in Remo (south of Kebumen in present-day Banyumas), and the latter in Karanganyar (present-day Bagelen) (in office, 1832-63). The first indigenous historian of the Java War, Djojodiningrat’s writings (ML97) are now in the Indonesian National Library.

As with prominent Irish Republican dynasties, they intermarried – one of Banyakwide’s sons being betrothed to one of Djojodiningrat’s daughters, their offspring becoming the father of Prabowo’s grandfather, Raden Mas Margono Djojohadikusumo.

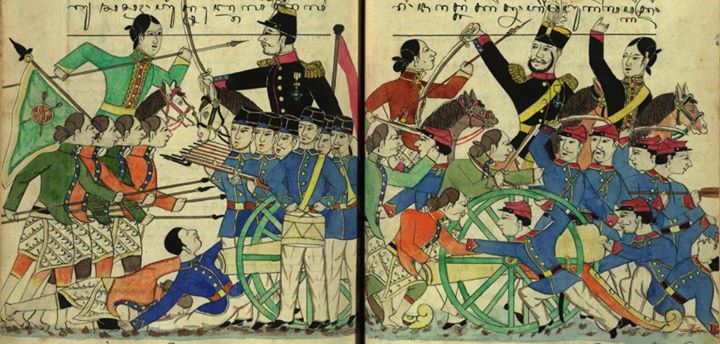

Raden Mas Margono Djojohadikusumo (lower right corner), the founder of the National Bank of Indonesia, is the grandfather of Prabowo Subianto (upper right corner), the controversial presidential candidate. Claims to a blue-blood nationalist family history has formed part of his campaign.

All this is charmingly chronicled in Mas Margono’s memoir, Herinneringen uit Drie Tijdperken (Reminiscences from Three Historical Periods; A family tradition put in writing) first published in 1970. That publication was my first contact with the Djojohadikusumo family as a callow student in Jakarta in 1973 and I used it with great profit throughout my teaching career at Oxford (1979-2008).

While such a family pedigree may be a source of pride, once one starts trying to ‘mine’ it for political purposes problems start. History is never clear-cut or easy, family history least of all. Appropriating it to enhance personal reputations is tricky.

As in post-Treaty Ireland, the Java War also constituted a form of civil war which not only pitted Javanese against each other but also saw the involvement of auxiliaries from other islands – who fought on both sides.

The Djojohadikusumo family suffered particularly: Djojodiningrat’s own father lost his life in an ambush set by Diponegoro’s top commander, Ali Basah Sentot (circa 1808-55), in Lengkong in the Sleman district to the northwest of Yogya (31 July 1826). As he lay dying, he placed a curse on the Sentot family forbidding any relative to marry into his line.

As for Raden Mas Margono, he was unable to visit Banyakwide’s grave in the Gombong area of Banyumas because he had placed a curse (pemali) that any relative who took service with the Dutch – as Margono had (he rose high in the Dutch colonial Village Cooperative Service) would not be allowed to approach his gravesite. All this is discussed in intriguing detail in his Reminiscences.

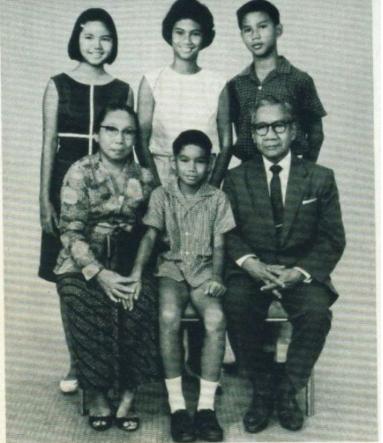

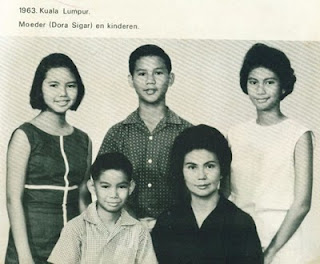

In a later generation the family relationships in relation to the Java war period became even more complicated because Mas Margono’s one surviving son, Professor Sumitro, married into a prominent Minahassan family – the scions of Benjamin Thomas Sigar who had served as a captain of native Minahassan auxiliaries (hulptroepen) for the Dutch.

Dora Siregar (lower right) is part of the Siregar lineage that fought with the Dutch colonial forces against the Javanese in the Java war. Son, Prabowo Subiato stands in the middle.

They took part in the destruction of the Javanese forces in the closing stages of the war. So again the ‘civil war’ aspects of the conflict took their toll. This is referred to amusingly in the memoir about Prof Sumitro – Sumitro Djojohadikusumo – Patriot, Economist, Teacher (eds Hendra Esmara, Aristides Katoppo and Heru Cahyono) (Jakarta: Yayasan Arsari, 2014) where on page 362 Sumitro is described referring jokingly to his wife as ‘(being) under a curse because your ancestors took sides with the Dutch General de Kock, while my ancestors took sides with the revolutionary Prince Diponegoro. So now you are being punished by having to marry me!’

So, once one looks for certainties in family histories one begins to enter a quagmire. History is never simple. Even Diponegoro – perhaps especially him despite his pahlawan nasional (national hero) status – continues to have a bad press in some circles in Indonesia. One thinks here of the Yogya kraton (sultanate), who see him as a traitor to his lawful sultan (HBV) for whom he was appointed guardian (1822-5), or the Kampong Jawa Tondano (Minahassa) community – descendants of Diponegoro’s principal religious adviser, Kyai Mojo – who see him as having been consumed by worldly ambitions – the santri (student of religion) view. Others like the late author and playwright, W.S. Rendra (1935-2009), bitterly criticized his contacts with the criminal underworld and his willingness to use bandits against the Dutch.

Diponogoro, widely remembered as a hero in modern Indonesia, was in fact a deeply controversial figure in various parts of Java.

The historiographical judgements of the Dutch – who tried to destroy the prince’s reputation by stating that he only rebelled because of disappointment at not being appointed Sultan and because a road was built over his property – likewise continue to poison perceptions of the prince in modern Indonesia.

There are also whole swathes of Indonesia where Diponegoro’s name means nothing – one thinks here of the Sundanese speaking areas of West Java, where the Dutch first contemplated exiling him (in Bandung): how many Jalan Diponegoro [Diponegoro Streets] or Diponegoro statues are there here?

In other places, like Minahassa, where Prabowo’s ancestor Benjamin Thomas Sigar hailed from, the abuse suffered by the prince was so appalling during his brief three-year period of exile there (1830-33) that legend has it that he flung his walking staff to the ground in the market-place making it shake as though in an earthquake.

At the end of the day the Java War was a tragedy which inflicted untold suffering on thousands (200.000 dead on the Javanese side and a further two million – a third of Java’s population – suffering the impact of the fighting).

The Belgian infantry officer Captain Errembault de Dudzeele (1789-1830) spoke of the appalling stench of 400 rotting bodies in the alang-alang (pampas) grass around Sunan Amangkurat I’s (reigned 1646-77) old kraton (court) at Plered on 9 June 1826 as he participated in the final assault on Diponegoro’s strongpoint. Where is the nobility here? As Pope John Paul II always said ‘war is part of the tragic history of the past’. It is something to be profoundly distressed by – not a source of elevation. Still less for a future president of Indonesia.

Peter Carey is Fellow Emeritus of Trinity College, Oxford, and YAD Visiting Professor at the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Indonesia (FIB-UI).

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss