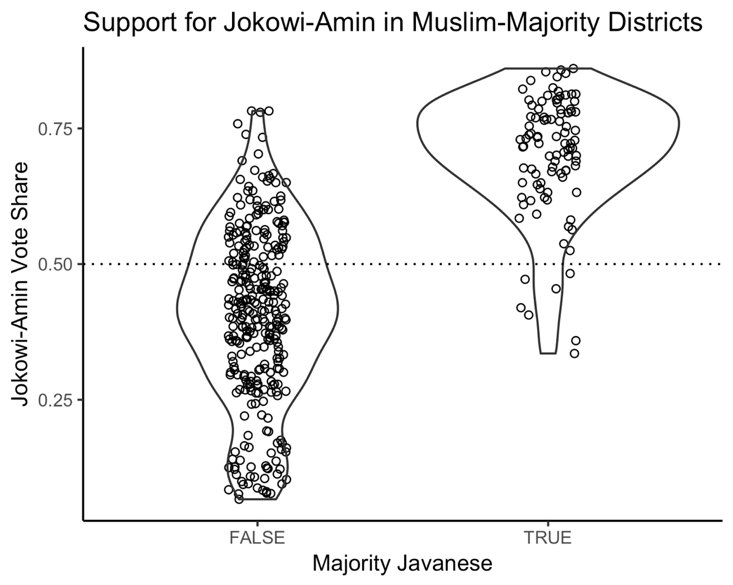

Recent analyses of Indonesia’s 2019 presidential election have shown conclusively that religion and ethnicity play a central role in explaining vote support for the incumbent president Joko Widodo. Jokowi prevailed in districts with majority non-Muslim populations, and his opponent Prabowo Subianto tended to earn most of his electoral support in Muslim-majority districts. But among those Muslim-majority districts, there is wide variation in Prabowo’s success rate, falling along an axis of Javanese versus non-Javanese. Although such analyses invariably face the problem of ecological inference, the data are “consistent with a growing cleavage between Muslims and non-Muslims alongside an ethnic cleavage between Javanese and non-Javanese.”

The coexistence of an ethnic as well as a religious divide highlights the need for analyses that take into account the organisational, ideological, and religious differences within Indonesia’s Muslim community. Within this mix, the role of Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) is particularly interesting: Jokowi’s vice presidential nominee, Ma’ruf Amin, was NU’s supreme spiritual leader at the time of his nomination, and his candidacy would seem to be an easy way to “lock up” more votes from NU members.

Indeed, one expectation that follows from Ma’ruf Amin’s nomination is that Jokowi would fare better in districts where NU has a strong presence than he would in other districts. With this in mind, we measured the relationship between the organisational strength of NU and electoral support for Jokowi across districts using a combination of survey and voting data. The results add important nuance to our understanding of the role of the “NU vote” in April’s election. Jokowi’s alliance with Ma’ruf Amin and NU did not increase the president’s electoral advantage in NU-dominant districts so much as eliminate a comparative disadvantage he faced in such districts in 2014. Yet even this modest boost was enough to be a critical factor in Jokowi’s overall victory, supporting the hypothesis that Muslim voters’ organisational affiliations do matter in explaining the outcome of the 2019 elections.

Counting NU by district

The central challenge in studying the relationship between NU and Jokowi’s electoral support across Indonesia is that it is hard to measure NU presence. Although the organisation claims wide membership, there are no data available on membership, organisational presence, or other aspects of its strength at the district level that would enable comparisons across districts.

Our solution to this problem is to estimate the relative influence of NU by district using data from the Indonesia Family Life Survey (IFLS). The fifth wave of IFLS includes a question about which Islamic tradition the respondent feels closest to: NU, Muhammadiyah, no Islamic tradition, or “others”

From this question, we construct two measures of NU organisational presence.

First, the variable Membership measures the fraction of all respondents in the district who declare that NU is the Islamic tradition s/he feels the closest to:

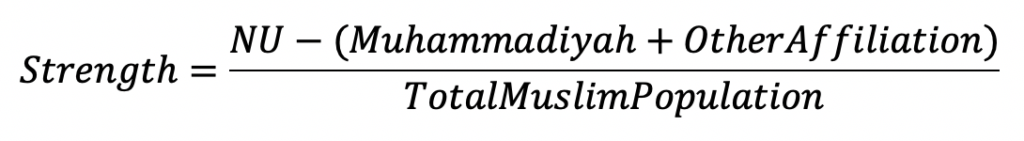

Second, the variable Strength captures the size of NU relative to other organisations. This is constructed by calculating the difference between the number of NU self-affiliated respondents and non-NU affiliated respondents as a fraction of the total Muslim population in the district:

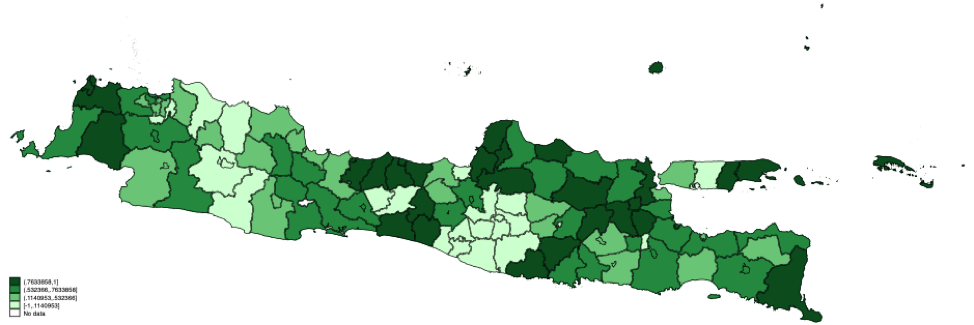

For Strength, a negative value signifies that other organisations have a stronger presence in the district relative to NU. In contrast, a positive value means that NU has higher presence in the district. To visualise these patterns, the map below displays the values of Strength at the district level in Java.

NU and Jokowi: is there a relationship?

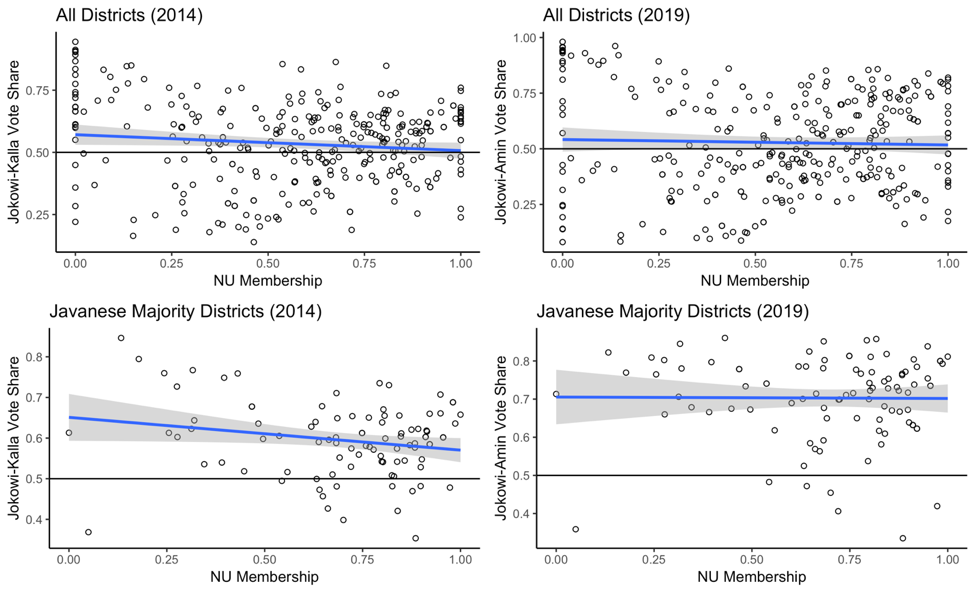

Combining district-level vote share data with these data on NU influence by district allows us to see if the two are related in any way. We can also compare the results from 2019 with the results from Indonesia’s 2014 presidential election, which also pitted Jokowi against Prabowo, to see if the relationship between NU and Jokowi support has changed at all. We plot these correlations below, both for all districts (the top two plots) and for Javanese-majority districts (the bottom two plots). The blue lines show the bivariate correlation between NU membership and vote share: what is the relationship, on average, between NU presence in the district and the vote share that Jokowi received?

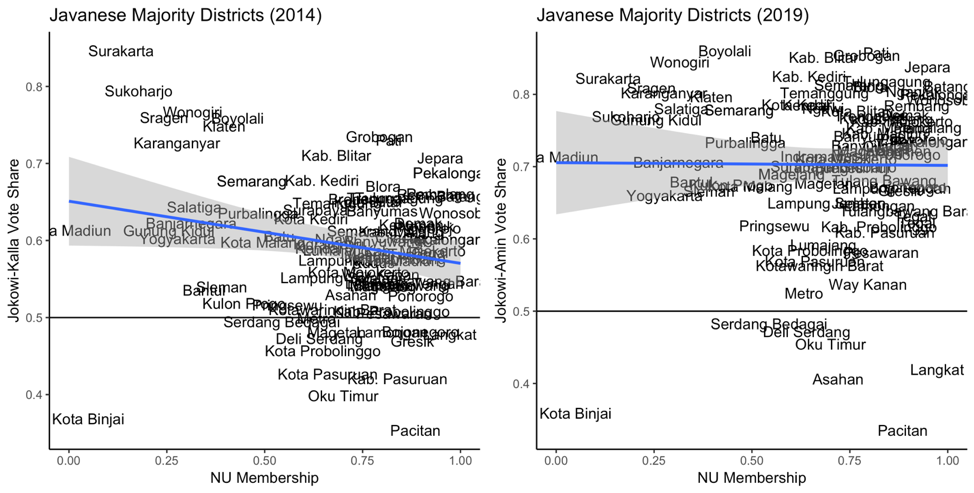

The patterns are surprising. NU presence does not have a positive correlation with Jokowi’s performance in the 2019 election. Instead, it seems that Jokowi performed worse in 2014 in NU-dominant districts, especially in Java, but this disadvantage has disappeared in 2019. To place these in context, below we show the scatterplots for Javanese-majority districts, with district names added.

Note that Jokowi won the majority of votes in most of these districts in both 2014 and 2019 (most of the districts plotted here are above the black horizontal line at 0.5). The difference is that Jokowi’s advantage grew in NU-dominant, Javanese-majority districts (see how the districts on the right hand side of the plot in 2014 shifted “up” in 2019).

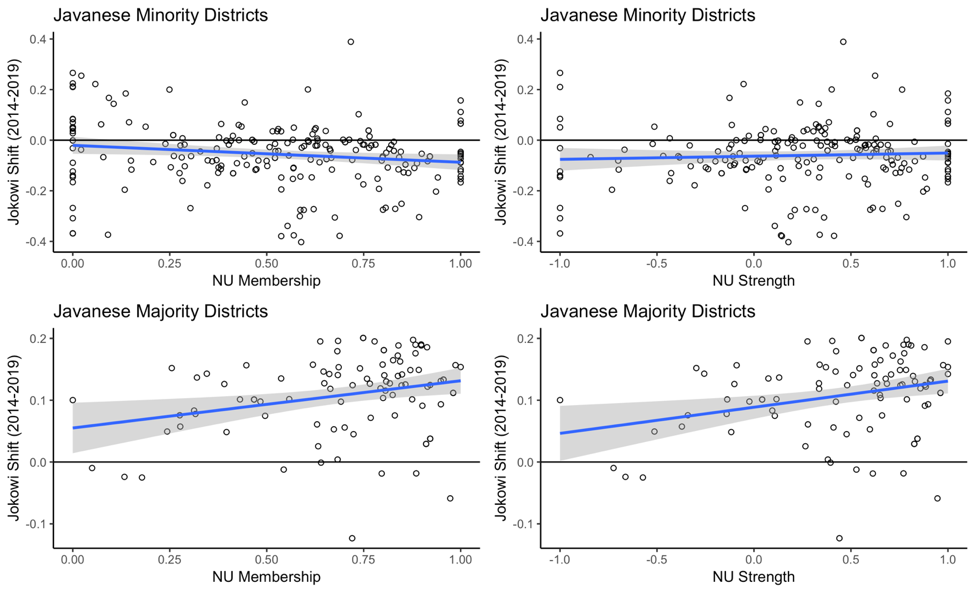

This argument is made clearer if we examine the changes in votes for Jokowi in 2019. This figure plots the change in Jokowi support between 2014 and 2019 versus Membership and Strength, both for Javanese majority districts and Javanese minority districts.

While we do not see a consistent pattern of changes in support for Jokowi in Javanese-minority districts, NU presence has a clear positive correlation with changes in Jokowi’s support in Javanese-majority districts.

The summary message from these graphs is twofold. There is no correlation between NU presence and Jokowi support in 2019. This might be seen as evidence against NU’s influence in 2019, but that is not the right conclusion, because there has been a shift within Javanese majority districts in support for Jokowi: the higher the presence of NU, the larger the swing in favour of Jokowi from 2014 to 2019. This story squares well with the strategy adopted by Jokowi’s campaign team: it suggests that by putting Ma’ruf Amin on the ticket, they were able to target NU voters in Javanese-majority districts who had not supported Jokowi in 2014.

A comprehensive statistical approach

Although these correlations are suggestive, they don’t allow us to disentangle the many possible factors that might have affected support for Jokowi. As a final step, then, we embed these analyses in a comprehensive statistical framework that models Jokowi’s vote share as a function of district-level sociodemographic characteristics, Muslim population share (variable Muslim), Javanese population share (variable Javanese), and fixed effects to account for differences across provinces. We allow the effects of Membership and Strength to be both additive and interactive with the Javanese population share (in statistical terms, the interaction variables would allow, for example, for the effect of NU Membership to vary based on the fraction of Javanese in the district). Moreover, since there are significant differences in terms of electoral leverage for different districts, for each regression we weight the observation by the total number of votes cast in each district. The unit of analysis in these regressions is district.

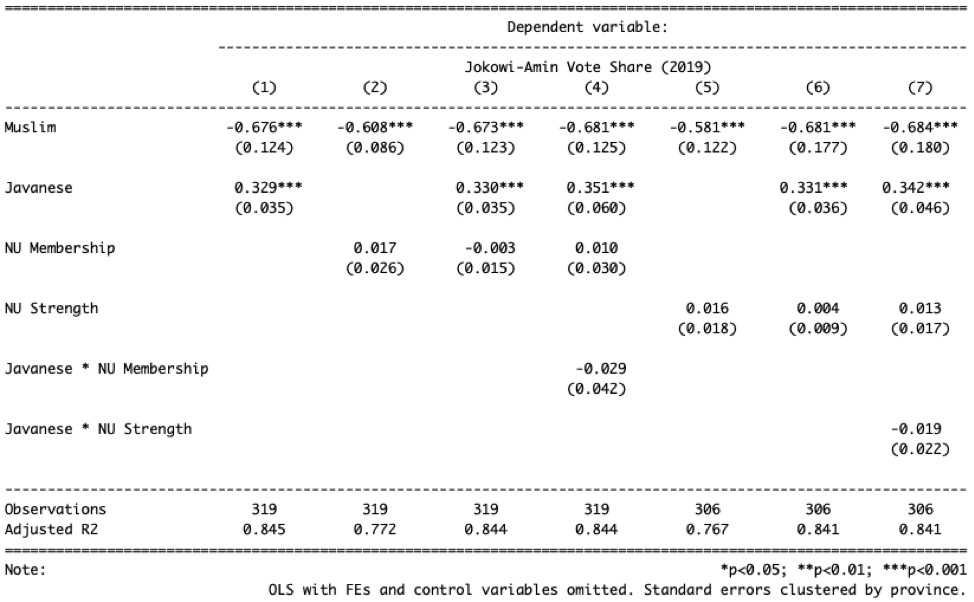

First we examine the correlates of Jokowi support in 2019. Reading these tables can be tricky, so we proceed step by step in explaining these results.

Look first at the lines for “Muslim” and “Javanese.” The regression coefficients for “Muslim” are consistently negative and highly statistically significant. We may interpret this as follows: if we compare two otherwise similar district, the district with more Muslim in average has less votes for Jokowi. By contrast, the regression coefficients for “Javanese” are positive and statistically significant, meaning that if we compare two otherwise similar districts, the district with more Javanese in average would have higher vote for Jokowi. These results are consistent with our previous work, these statistics suggest that ethnicity and religion both help to explain district-level Jokowi support in 2019.

As expected from the discussion above, there is no correlation between NU membership and support for Jokowi in 2019. We see this from the lines “NU Membership” and “NU Strength,” which are statistically insignificant both alone and when interacted with Javanese. In other words, NU presence gave neither advantage nor disadvantage for Jokowi-Amin vote in 2019.

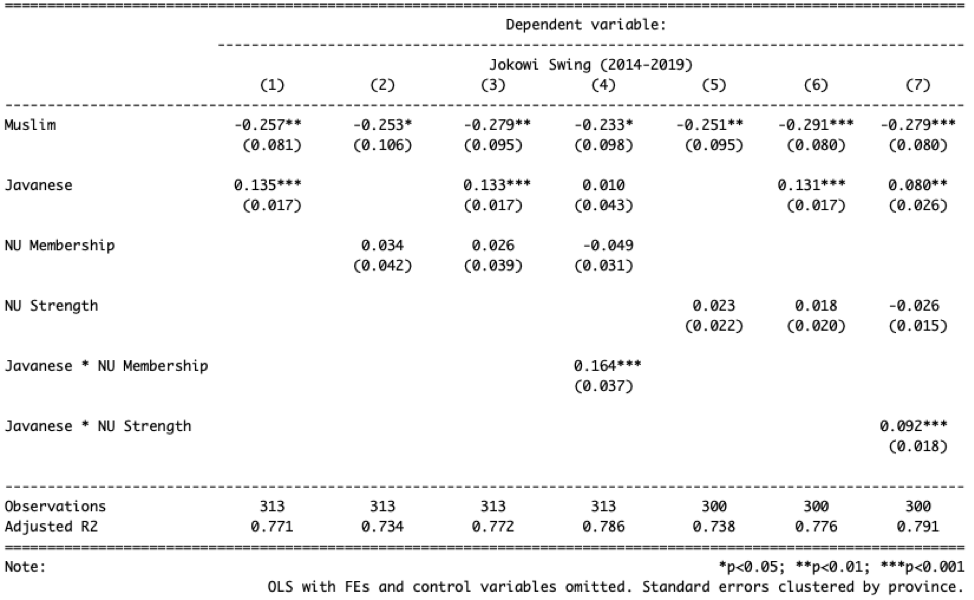

But if we examine instead the change in support for Jokowi between 2014 and 2019, we find strong evidence that NU membership matters. The next regression results repeat those from above, but use the shift in support for Jokowi (or “swing”) between 2014 and 2019 as the dependent variable.

Now we see that “Javanese * NU Membership” (column 4) and “Javanese * NU Strength” (column 7) are highly statistically significant. This suggests that, one of the main predictors for the swing in Jokowi’s votes relies on two interacting factors: the fraction of Javanese in the district and the strength of NU presence. Hence, this model predicts that the highest swing in support for Jokowi would take place in districts where both the fraction of Javanese and NU membership is high.

To illustrate this point, we plotted the relationship between NU membership and changes in support for Jokowi at different levels of Javanese population share. The black line with the grey band shows the predicted correlation between NU Membership and 2014–2019 vote swing across various levels of Javanese population. The red error bars break districts up into three groups: the lowest, middle, and highest terciles of Javanese population.

We see that at low and medium levels of Javanese population share (groups “L” and “M”), there is no correlation between NU membership and Jokowi’s vote swing, but as we move to a higher share of Javanese, the effect of NU grows stronger and more statistically significant. As a matter of fact, once a given district passed the threshold of 50% Javanese, the average vote swing for Jokowi is more than about 5 percentage points, almost reaching 9 percentage points for the highest tercile (“H”).

Implications for Indonesian politics

These results suggest that putting Ma’ruf Amin on the presidential ticket was a crucial factor in Jokowi’s victory in 2019. We cannot conclude that the choice to run with Ma’ruf was decisive—perhaps another VP contender like Mahfud MD would have had the same effect—but the evidence is consistent with the hypothesis that Ma’ruf helped Jokowi among NU voters.

Jokowi and NU: the view from the pesantren

Islamic boarding schools are ground zero for Jokowi’s efforts to win over the Muslim grassroots. Ideology and patronage are both playing a part.

More broadly, the evidence we have presented suggests that in Indonesian elections, vice presidential candidates matter. The data are consistent with the argument that putting Amin on the ticket helped Jokowi to win by capturing a missing demographic of NU voters in Javanese-majority districts (and without Jusuf Kalla on the ticket, as we know, Jokowi’s support from South Sulawesi plummeted). Looking forward, the question that follows is how Javanese and NU interests will shape the character of Indonesian democracy in Jokowi’s second term.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss